“They aren’t statistics. They are human lives,” says Juan Luis Toledo Sanchez, member of the autonomous cooperative Cimarronez (or C.A.C.A.O., by its Spanish acronym), in Mexico City. He is part of the team that, for five years, has been mapping the indigenous people in Mexico’s capital.

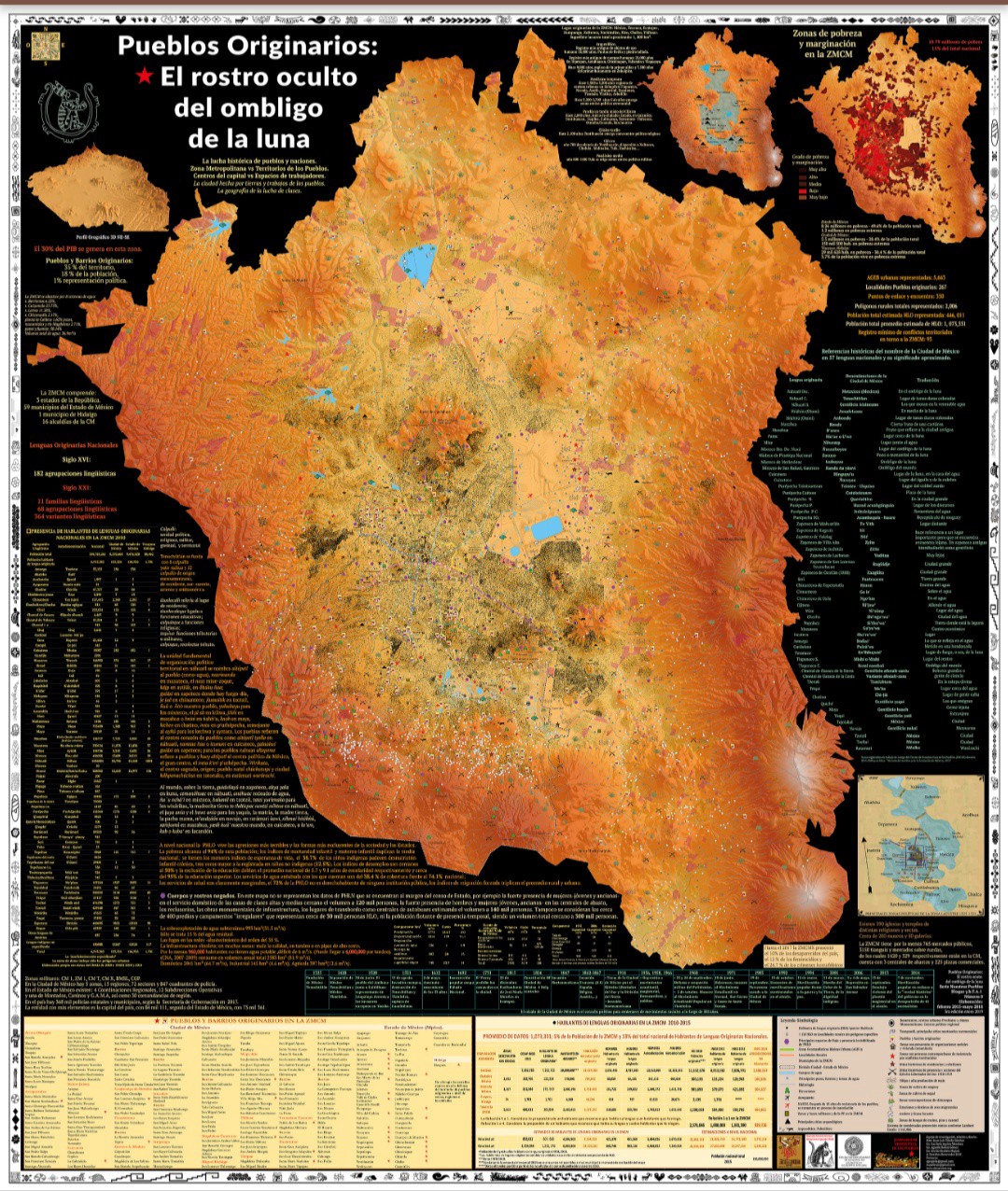

The cartographic map Pueblos originarios: el rostro oculto del ombligo de la luna (Indigenous People: The Hidden Face At The Center Of The Moon) made by the Cimarronez, shows the presence of the indigenous people in Mexico City, something that not even the State or non-profit organizations made before in the country, even though Mexico is one of the most diverse nations in the world in relation with its indigenous cultures.

They mapped the 2.1 million people who recognize themselves as part of the indigenous culture in Mexico City and its Metro Area — 7 percent of the 30 million people living there. For comparison, 2.9 million Native Americans live in the United States, just 1 percent of the 300 million people that live there.

Mexico City has 13 percent (446,000) of the people who speak the 68 indigenous languages in the whole country — that means that the capital is a region that should take notice of their presence, but that isn’t the case. Although being historically a Nahuatl region, people from other states have arrived and lived there, speaking their own languages: Zapoteco, Triqui, and Mixteco from Oaxaca, Maya from the Yucatan peninsula, Tzotzil and Tzental from Chiapas. Those are just some of the languages that have added to the Nahuatl and Spanish spoken in Mexico City.

Juan Luis Toledo says that “many investigations have a prejudice against the indigenous people because they show the indigenous people in terrible conditions with religious fanaticism or with exotic food and dress. We say no! We say the indigenous people exist beyond that.” He added, “the oppression and the history and geography that show only the ruling class and erases the indigenous.”

The map tries to be a humble effort as a tool to organize against power, according to the document written by Toledo Sanchez that accompanies it.

Many of Mexico City’s indigenous habitants are migrants. They leave their hometowns, in states like Oaxaca, Guerrero, Chiapas, or any of the other 31 states in the country, to find a better life. They also find racism and discrimination, both from the society and the authorities, says Toledo Sanchez.

The map is available online at cimarronez.org but only as a static image, not in high resolution or as an open archive. It also covers subjects related to what indigenous people live in Mexico City and its Metro Area: the rural areas, ancient urban centers and the conflicts for the land. It shows the social division between the poorer class (many of them indigenous) and the middle and high class. One of the main conflicts that the map shows is the relationship between the metropolitan area in Mexico’s center (it includes Mexico City, the state of Mexico and Hidalgo) covering an area of 7,815 square kilometers and Mexico City.

One of the main conflicts at Mexico’s capital is the relationship between the metropolitan area and the indigenous people. The document that accompanies the map shows how the metropolitan area and urban areas in Mexico are where the capital is supported through labor exploitation, dispossession of the land, and centralization of the ruling powers.

The public policies in Mexico City erase the indigenous people who migrate from other states, says Toledo Sanchez. Around 300,000 of the indigenous people in Mexico City and its Metro area aren’t counted on the census, because they work at the Central de Abastos (Mexico’s biggest market), or as stonemasons or cleaning houses, so they are omitted by their bosses. The map shows that there are 400 irregular encampments all over the Metro Area with at least 30,000 people living there, but they have also been left out from the census.

According to Cimarronez, because they are considered “outsiders” the politicians don’t consider their rights to water, services, health, education, land and social programs.

This map makes people conscious of that relationship and the historical presence of the indigenous people in Mexico City, even before it was named this or conquered by the Spaniards in 1521.

During the investigation, Cimarronez found Mexico had experienced millennia of migrant processes, even the foundation of Tenochtitlan in 1321 is one of them. Back then, there were mobility circuits in Mesoamerica, from Oaxaca or Maya territories.

“The Conquest of Tenochtitlan was more important than getting to the moon,” says Toledo Sanchez. He believes that to have cities in America was the most important thing for the Spanish crown and capitalism because that permitted the European countries to reproduce capitalism in the New World. Hence the map about the indigenous people.

“We said: let’s think where are we, how many are we, who are we, as a need, and then this was the result, a map with 25 sections and 25 layers of information.”

The Diagnostic of the Mexico City Indigenous People, made by the local authorities, recognizes their historical presence. In the 1940s they represented just 1.2 percent of the inhabitants at the country’s capital. However, says Toledo Sanchez, the government established the concept of “outsiders, not from here,” to erase from the memory their presence. “We show that there are at least 1,500 years of historical presence of the indigenous people, and they aren’t ‘outsiders,’ because it’s a territory where they live.”

Freelance Journalist in Mexico. Story-teller and traveler.