The Size of Countries is Not Meaningful in Any Sense

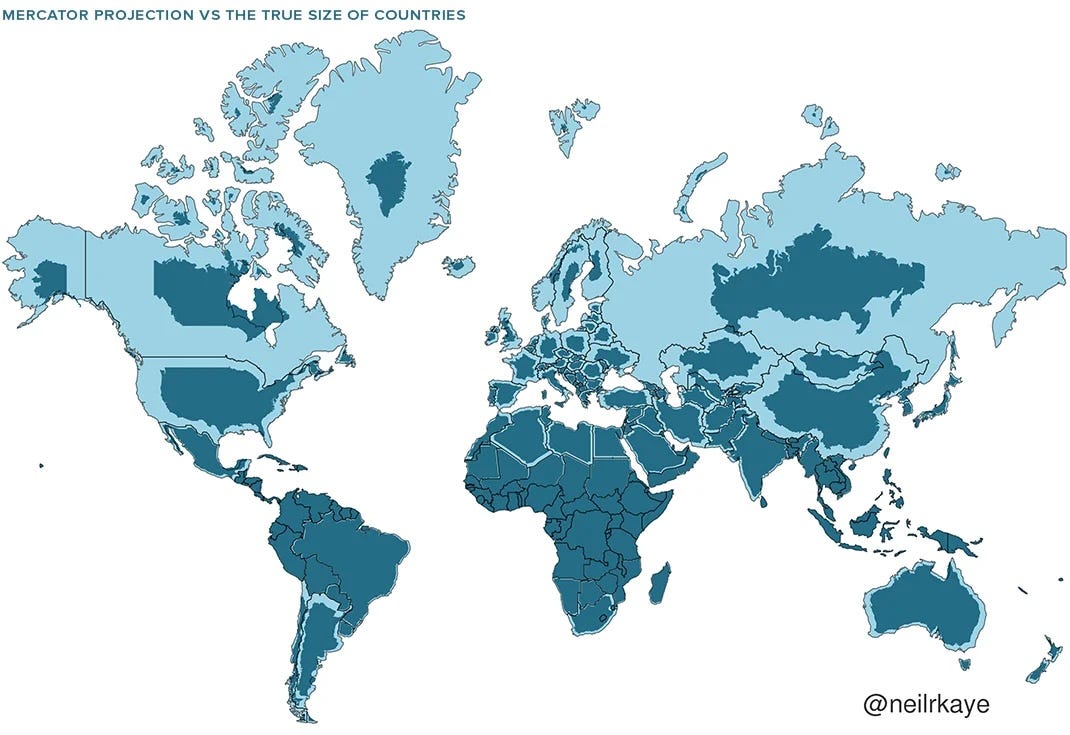

You’ve surely seen this map or a variation of it somewhere on the internet. If, like me, you’re a professional information designer, you know it’s part of an entire genre, including animated versions of it:

Or the effect of distortion on simple concepts like Great Circle Distance. This is the area within 5000km of Paris on a Mercator projection emphasizing the geographic distortion that happens the more north you get. You would expect a circle but instead get a shape reminiscent of a guitar pick.

Or interactive versions like this one by Ian Johnson that let you examine how different projections distort the shape and position of countries in different ways.

If, on the other hand, you have no idea what’s going on here, the short answer is that in transferring the shape of the surface of the Earth from a sphere to a flat screen you have to make certain decisions about whether and how much you want to maintain accurate representations of distance, area, grid alignment and other features. This is an editorial decision, there is no one right way of showing geography. Like most problematic subjects, Aaron Sorkin’s surrealist comedy The West Wing provided an overly idealistic and peppy explanation of the problem of map projections.

These maps are popular because they touch on the contingent nature of information display and emphasize the importance of revealing the human hand in communicating information. Sadly, we’re so constrained by our limited data visualization literacy that we can only really discuss these design choices with the venerable choropleth map because everyone learned how to read it in their 7th grade geography course. Every time one of these maps shows up on Reddit or BlueSky it is met with much excitement and adulation. Well-meaning people have claimed that the Mercator projection has made us think that northern hemisphere countries are better than equatorial and southern hemisphere countries because their size is exaggerated. All of that is a real problem because the “amazing” quality of these maps is shared by another amazing map.

Land doesn’t vote, the saying goes. And even when administrative regions (whether practically empty states in the American West or tiny countries in the EU) exert an outsized influence that’s not a reference to their geographic area but rather to their population. There are times when you need an accurate understanding of the area of land. You might be a farmer looking to expand your acreage or planning a new Amazon warehouse, but it has almost nothing to do with politics, culture or society. When we celebrate maps that make land important we are unintentionally enabling much more problematic maps like the Impeach This map.

There is a difference between maps created to show the distortions inherent in map projections and those created intentionally to mislead. But for readers it’s not so clear when we lack the tools to talk about them meaningfully. The distortions of the Mercator projection don’t just exist in some theoretical vacuum—they’re a reminder of how easily visualizations can be weaponized to amplify or bury ideas. To counteract this, we need to get better at asking specific questions: Why this projection? Why these data choices? What’s being highlighted or hidden? By learning to spot and articulate these design decisions, we can go beyond cheering for “amazing” maps and start seeing when they’re actively doing harm. Until we learn to name the ways maps shape narratives and teach others to do the same, we’ll stay stuck in a cycle of celebrating the familiar while missing the bigger picture.

Back in 2015, I attended the NACIS conference in Fargo, North Dakota. Fargo was selected because it was nearly at the center of North America but, as anyone who was forced to fly there on a series of progressively smaller airplanes knows, it’s actually much farther away from the rest of North America than, say, Chicago. That’s because in the modern world “close” has little to do with area and more to do with the transportation networks we’re embedded in via road, rail, sea lanes and air routes. The way we refer to sea and air travel (routes and lanes) is a reminder that even the crow doesn’t fly in a straight line.

But to talk about the networks on which we move goods, people, electricity and information would require people to know something about networks. Unfortunately, we don’t learn about networks in the 7th grade like we do maps. And it doesn’t stop there, if you ask a data visualization expert they’ll often tell you that you, too, do not need to learn how to read a network visualization or a flow diagram or any other kind of complex data visualization. Which is unfortunate because networks better explain the modern world than most amazing maps.

As a result, we’re stuck with only a few familiar methods for displaying anything more complex than a bar chart or line chart. Maps are one of those few methods that we know people can read. That familiarity gives us the ability to then have a second-order conversation about the data transformation and other information design decisions we have to make when it comes to any kind of map or chart or diagram. And that’s an interesting point to make, that’s why those maps are so popular. But there are so many other interesting points to make about data visualization, and we need to spend more time popularizing those rather than just repeating this same fact about map projections. If we don’t move on to other interesting points about information design, then we’ll never grow as readers or practitioners.

Principal Engineer at Confluent. Formerly Noteable, Apple, Netflix, Stanford. Wrote D3.js in Action, Semiotic. Data Visualization Society Board Member.