Activist and technologist Murray Cox has been described as a “Lone Data Whiz” who is Airbnb’s “Public Enemy No. 1 in New York.” These monikers aim to personify the amount of data, maps, and reports Cox has collected and created to understand Airbnb’s impact on communities.

But Cox explains that his project, Inside Airbnb, was simply in response to two of his beliefs: first, that housing is a human right that has been commoditized, second, that data might further the conversation.

“It was a civic project, my civic responsibility to contribute to the city,” Cox said of starting the project in NYC. “In the same way that other housing activists do their organizing work, I used my data skills to contribute [to] the city.”

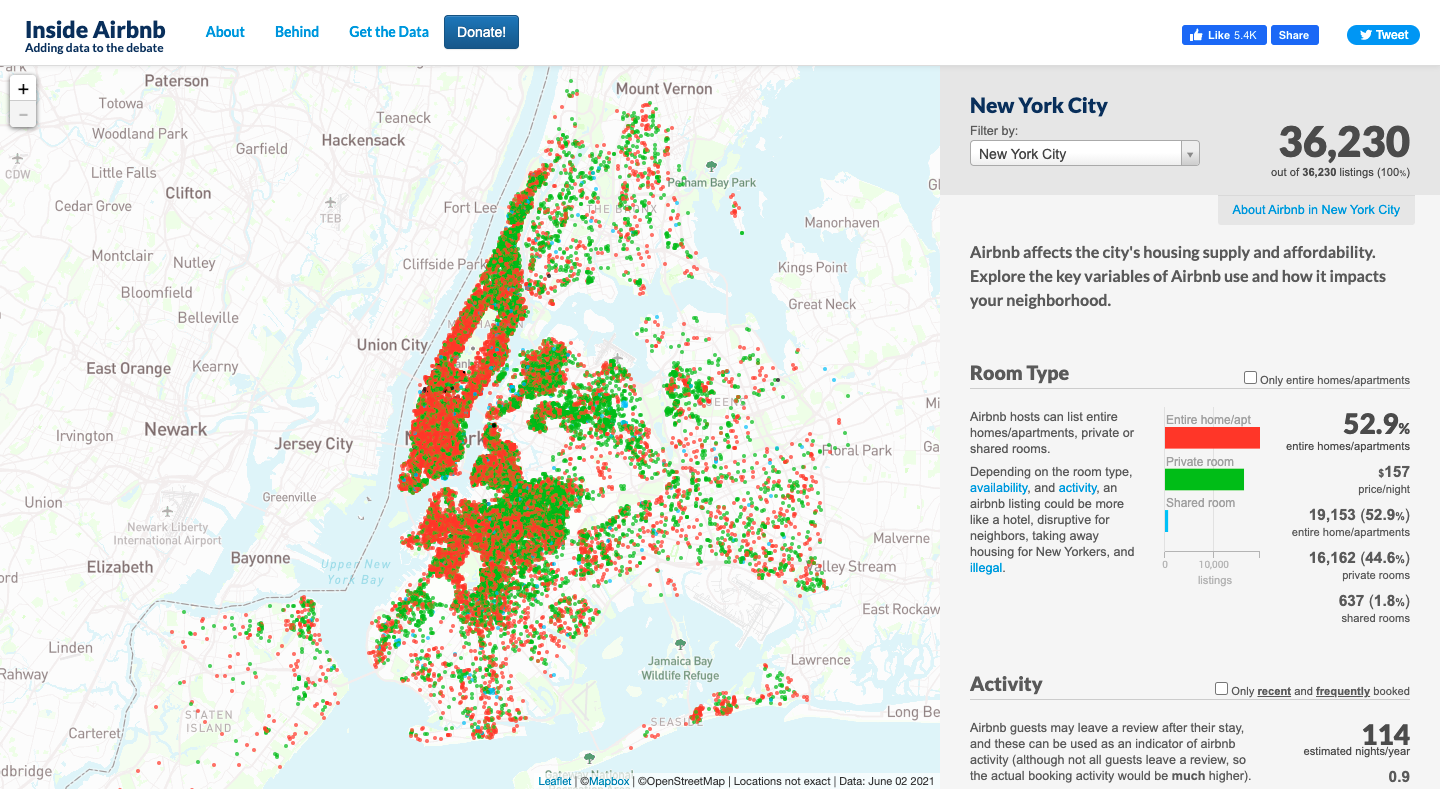

He launched Inside Airbnb in 2014, after teaching a youth workshop on gentrification in New York City’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood using data analysis and visualization. He began scrutinizing Airbnb’s publicly released data. On his website, users can download the most recent year of data for free. The data he collects includes details about hosts, like the host’s self-reported location, the number of listings, as well as the price and room type of each listing. With Inside Airbnb, Cox visualized this data into dashboards for each city, using Mapbox Studio and OpenStreetMap.

Two years after the launch, Cox released the site’s first major report with fellow data activist and independent co-author Tom Slee, who collects data of his own, separate from Inside Airbnb’s. Cox and Slee analyzed data that Airbnb had publicly released about its presence in New York City in December 2015 — and found that the company had removed over 1,000 from November listings before releasing the data.

All of the removed listings were for entire homes whose hosts were renting out multiple entire homes, as opposed to only one home, presumably their own residence. These listings are the biggest concern to activists like Cox who fear they are being operated by commercial hosts, not residents sharing their own homes. Airbnb then presented the November data as an average day of Airbnb’s operations in New York City, with only a small number of commercial hosts, which Cox and Slee found to be untrue.

Now seven years into the project, Inside Airbnb has expanded to 85 cities and regions in over 25 countries. The website includes an interactive map and summary of listings for each location, along with downloadable data. In a pre-pandemic world, Cox would travel to speak at conferences about his findings. He fields academic and journalistic requests almost daily. He even met with Airbnb in February 2019, where they discussed a proposal to regulate home sharing in New York.

A bill requiring registration for short-term rentals has been discussed in the New York City Council, which held a hearing on it in September. Murray, who has been working on the legislation with the Coalition Against Illegal Hotels, gave testimony at that hearing.

“What really surprised me is how big [Inside Airbnb] grew and what impact it had,” he said.

Today, Cox is grappling with the scalability of Inside Airbnb as an open-source data project. He considers his work first and foremost as housing activism and wants the data to be free for activists to address issues in their own cities.

But the project does come with expenses like proxy servers, cloud storage for data and data transfer costs for when people download his data — all of which comes to a few thousand dollars per month, Cox said. He said he generally doesn’t pay himself. To support the project and himself, he works part-time in product development and management, and infrastructure in the art technology space.

“How do I release free data because that’s going to help activists? But at the same time, I have expenses that I have to pay,” he said.

Besides funding the project personally, he is requesting payment to access archived data that is more than a year old. He recently removed archived data from his site — because he found that some were simply scraping it on their own instead of contacting him to request it. Today, access to one city’s archived data costs $300 for academics or other institutions doing research related to Cox’s mission. Commercial researchers or academics studying a topic unrelated to Airbnb’s mission pay $500 for that data, according to a pricing guide on Inside Airbnb’s website.

Data from the last 12 months is still free for all to use. Activists, journalists and residents, as well as governments doing work aligned to Inside Airbnb’s mission can request access to archival data for free. But some cities and regions, like San Francisco, New York City, and Vaud in Switzerland, also pay him a few hundred dollars per month to access the data. Cox has also created an advisory board of activists and researchers, which aids with finding potential collaborators and funding sources for Inside Airbnb.

Given these hurdles, Cox said he would advise data activists to think about how they can garner community and financial support to scale their project if needed. Finding communities of civic technologists, like Beta NYC, is one way to find like-minded people to join a project.

He added that working with traditional advocacy groups who aren’t involved with data is equally crucial, since it brings data activists closer to communities.

“It’s really important to ground the work with people that are already doing it and might have been doing it for a long time and might have a better appreciation or be closely connected to the community that are most impacted by the issues,” he said. “I think most technologists are not that well-connected to the issues or the communities impacted — or not doing their own activism.”

Despite the time and cost of maintaining Inside Airbnb, Cox said he feels that the project is most “justified” when he sees cities use his data in the process of instituting housing regulations. He is also hopeful that more people in data fields will recognize that they can use their skills both for financial gain and societal improvement.

“A lot of people that have data skills are interested in projects just to make money,” he said. “I think there’s also an opportunity to use technology and data to help society.”

Ilena Peng is a freelance journalist and a graduate student studying data journalism.