I have this vision in my head: I see an individual earnestly weighing how to vote in an election. But rather than resorting to social media or political advertising to inform their choice, they turn to data about their community. Their aim is to use these data to reflect on how conditions have improved, or deteriorated, and to understand what issues need the most attention locally.

I can conjure up another pleasant daydream: I imagine two family members on opposite sides of the political spectrum looking at data visualizations on a host of issues—poverty, educational attainment, immigration trends. Then, they each speak from the heart and consider what can be done to address issues exposed through the data. It’s hard work, but they begin to understand each other’s perspective and see a middle path.

I know these sound like flights of fancy. After all, who among us actually uses public data to decide how to vote? Very few of us, I’m sure. I can’t help but wonder, however, if we could all benefit by nurturing this capacity in us.

Why try to rebuild political dialogue through data?

These days, it seems, we crave more and more data in so many facets of our lives, yet we disregard its power in political discourse by not seeking out unbiased facts on issues or community well being. Data, for example, is central to a well-functioning business, with real-time indicators and sophisticated dashboards regularly leveraged to plot next steps. Many of us, too, now measure our sleep, steps, and daily exercise. We view the results as progress graphs on our phones and watches and take action accordingly. And in my realm of work, where I run a data storytelling consultancy to serve organizations working to improve the social good, I see that universities, government agencies, and foundations increasingly want to learn how they can better leverage and communicate data to champion their work.

I don’t mean to suggest we willingly keep data at arms’ length in political discourse. Many of us, I’m sure, would invite data into our lives to help us perform civic duties like voting. It’s just that we’re collectively overwhelmed by the volume of unhelpful political messaging that permeates our minds—social media feeds that influence our thinking; political advertising that’s often built to make us feel tense; and rhetoric from candidates that may exaggerate actual conditions. It’s not easy for the everyday voter to think about available data as a tool for education when there’s already a cacophony of seemingly urgent messages drowning out everything else.

Despite these challenges, we should actively try to insert data into discourse, because of the power of data to bridge divides and help us get beyond angry rhetoric. The common post-election refrain I keep hearing from friends, family, and colleagues is that they just can’t fathom why someone voted for the person in the other party. Yet the election results are pretty clear that votes were roughly evenly split between the two presidential candidates, which means that many of us simply don’t understand the perspective of the other half. How could we when we’re battered by political messaging that may only confirm our own political biases?

Relaying data about issues impacting our everyday lives, in essence, would allow us to find common ground and help us read from the same script—and such data would counter the foreboding images of doom in political discourse and social media feeds that taint our understanding of the world.

How can data help combat polarization and unhelpful rhetoric?

The question of why to do this work to leverage data to inform the electorate is easier to answer than the how to do this. After all, the media channels noted above—political advertising, social media content, candidate rhetoric—are strong forces that can’t easily be tamed. However, there’s reason for hope if we start by lifting up data about, in particular, local community. You see, local work offers the most potential to bridge divides. CivicPulse, in newly published research with the Carnegie Corporation, found that local government leaders say that polarization is not likely to impact their work. The smaller the community, in fact, the less polarization plays a pivotal role, according to their survey.

Our local communities can indeed be safe harbors from polarization and a means by which we stitch back together a sense of mutual understanding. Local community may well have played a more vital role in understanding our world, say, 100 years ago. These days, our outlook is much broader as our horizons have expanded. Yes, we’re more worldly, which is good, but we’re also more susceptible to fear-inducing stories we hear happening in other regions of the country.

The evolution away from community as a way to understand our world perhaps began to take hold as national media, both TV and newspapers, started to drown out local reporting. Then came the Internet, which further erased geographic distance, and, along with cable news, enabled us to focus only on digesting media related to our interests. And finally came social media, which allowed people to find common outlets for their anger in places distant from home. As a result, that sense of local community that helped keep us sane and less polarized lost its influence.

Transforming wide-ranging local facts into community education

On the positive side, however, we’ve also become more adept over the last 20 years at finding, publishing, and visualizing data about our communities. I began working with community-level data in 2002, when I helped launch a data website, kidsdata.org, to raise awareness about children’s issues in California. Back then, it felt like me and my colleagues were on the cutting edge by visualizing and communicating data about local child well being. Since those early days, a range of web tools providing community-level data have proliferated. I keep a catalog on my company’s website listing resources with data for California communities, and there are now about 75 such data tools in this catalog.

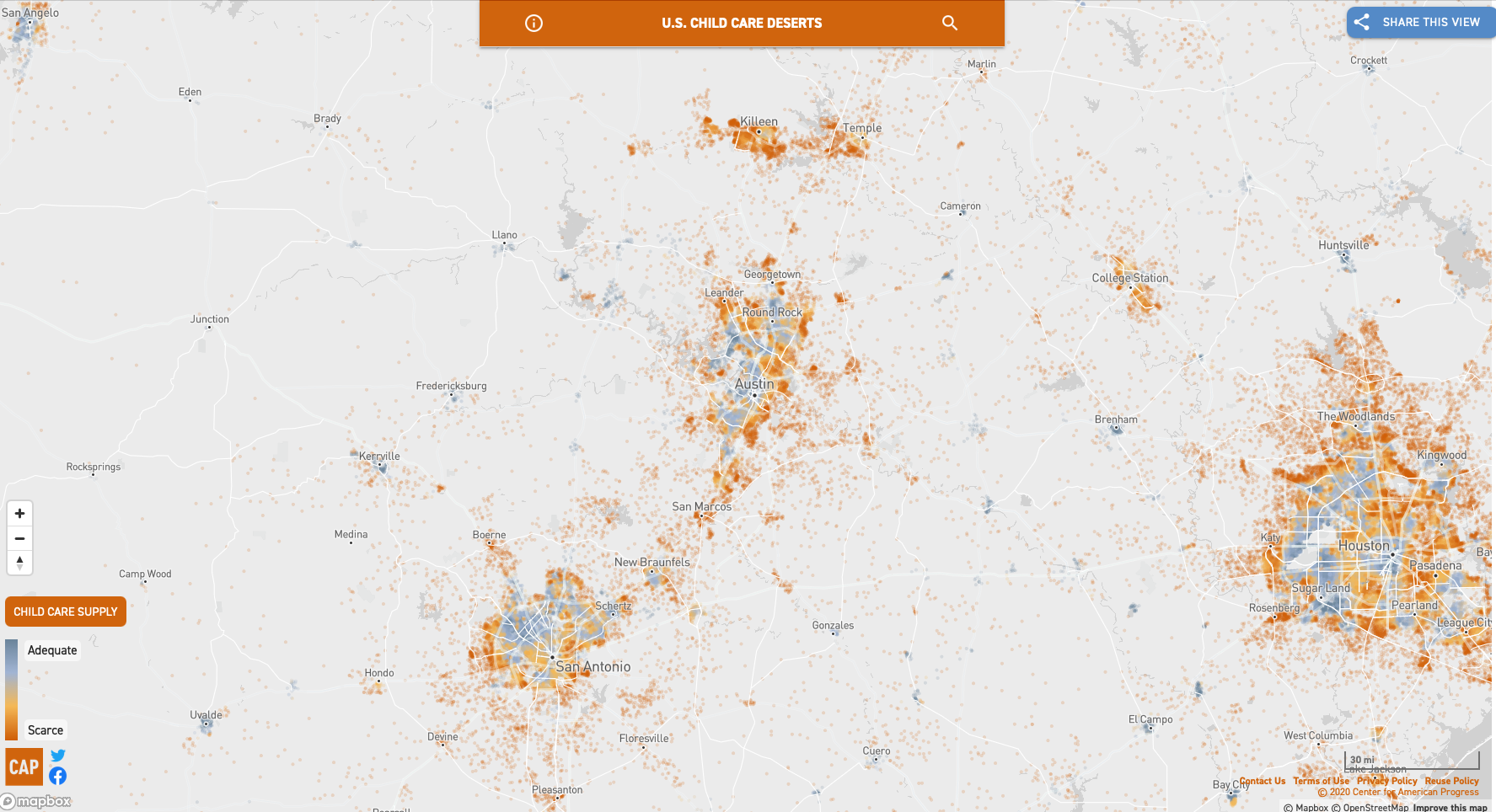

Many of these sites—such as County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, the CDC’s Places website and AARP’s Livability Index—even have local data for essentially every community in the United States. In short, the data is there for us; we just need to mobilize it.

I know from the work I do with my clients that they’re eager to harness data about community and transform facts into action. My clients’ aims may be focused on encouraging local business leaders to join a collaborative; providing maps and graphs to elected officials to persuade them to pass a policy; or visualizing data about community conditions in order to obtain funding.

Those are all worthy goals, but we also need to see local data as an asset to help educate the electorate. Twenty years ago, this wasn’t an option, given the lack of data, but local data is readily available, visualized beautifully through tools that are thoughtfully crafted to help shape our understanding of our communities. Granted, these indicators are not available in one place (and probably never will be). That’s a solvable problem; we can guide people to where to go for data on specific topics. And in all likelihood, the everyday voter may need some hand-holding, too—some kind of curation of the data, perhaps through stories that can add needed color. Here, too, there are workable solutions.

There are numerous other obstacles in our path. Funding for government data sources that fuel these data websites could dry up. Facts could be manipulated by domestic (or even foreign) agents. And some of us may become (or may already be) skeptical of data from public sources. Those are indeed obstacles, but they’re not reasons to give up on this endeavor.

What I’m actually most concerned about is the lack of collective action. It’s striking to me that all of these organizations which build their various data tools work on their own islands, and don’t typically join forces. We need to change that mindset to have any chance of combating the power of advertising and social media in political discourse.

I, for one, am keenly interested in helping to corral together the vast data resources we’ve assembled about our local communities, then finding ways to marshal these data for the benefit of political discourse. My hope is that, if we can establish a beachhead by using data to inform our understanding of place and local community, we can slowly begin to provide people with clear-headed ways to understand their world—and each other.

Who’s interested in joining this journey? And who knows of similar initiatives focused on leveraging data to support discourse? I’d love to hear from you at andy@hillcrestadvisory.com.

Andy Krackov runs a consultancy, Hillcrest Advisory, to help social sector organizations in California and elsewhere communicate and tell stories with data. A decade ago, when he was a program officer at the California Health Care Foundation, he worked closely with government agencies in Sacramento and Washington, D.C. to open up public access to their data.