For many researchers and analysts, using large federal, state, and local surveys involves tabulating or organizing categories of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, sexual orientation, or a host of other identities and demographic characteristics. The specific categories that are available in federal data and how they are collected, ordered, and coded are defined by individual federal data collection agencies as well as overarching guidelines published by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Here, we discuss the large changes to federal data collection guidelines from OMB and how you can be an active participant in how OMB and other agencies decide what data and how to go about collecting it.

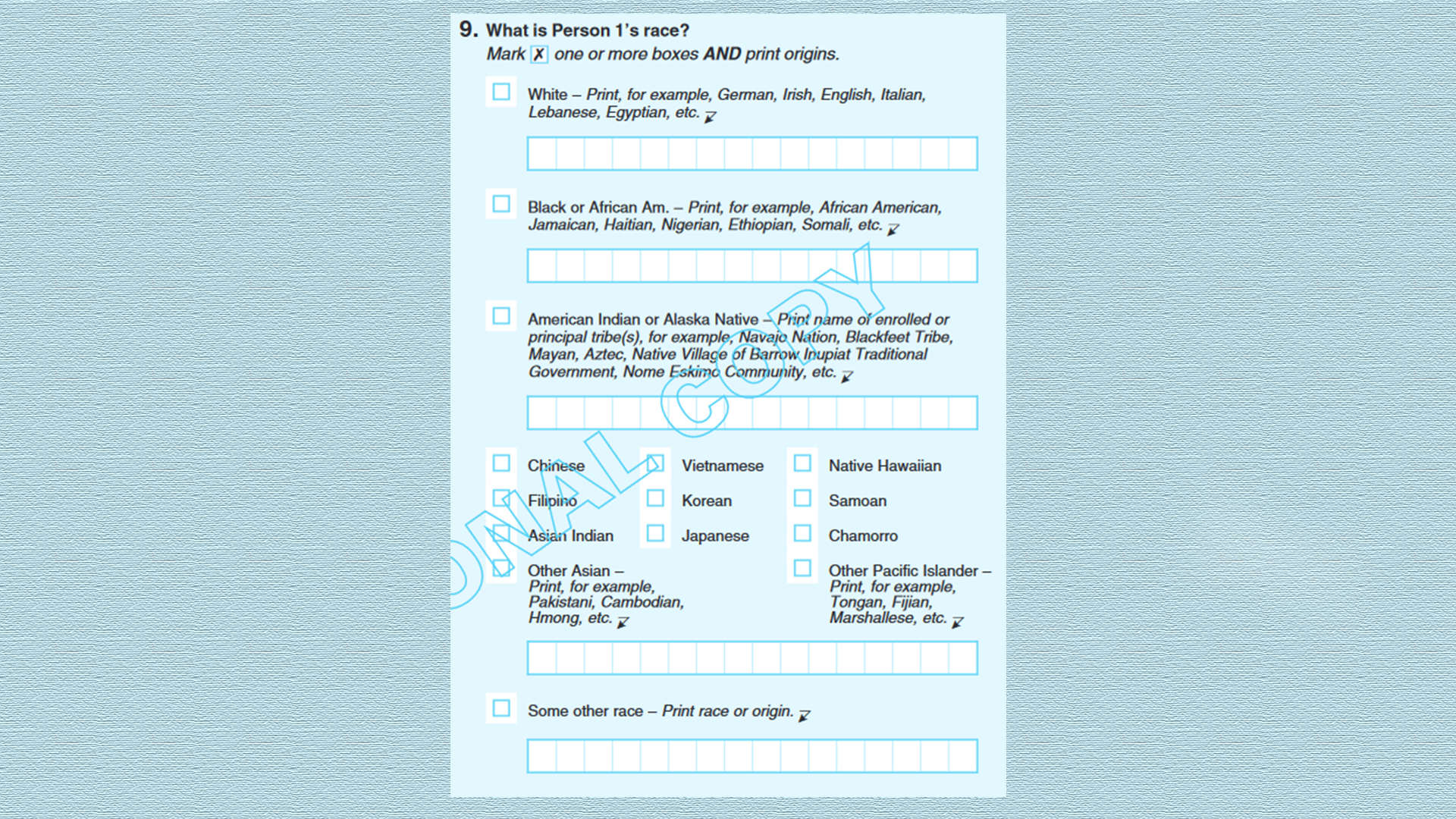

Existing data collection and usage guidelines are not fixed in space or time. Racial categories, for example, have changed dramatically over the 24 decennial Censuses that are conducted every 10 years starting in 1790. In the first three censuses in 1790, 1800, and 1810, for example, there were three racial categories: “Free white males, Free white females”; “All other free persons”; and “Slaves.” Those categories have obviously changed over the past two hundred-plus years to be more inclusive and representative of the US population. The most recent 2020 census included 15 separate identified categories to which survey respondents could provide additional details by writing in specific racial and ethnic identities.

Today, OMB, the Census Bureau, and many other data collection agencies—as well as other organizations, researchers, and advocacy groups—discuss and debate the best ways to collect identity information. The Census Bureau, for example, is currently debating whether and how to change the set of questions used to collect information on disability status.

How did we get to the 15 racial categories that appear on most Census Bureau surveys (and most other government agency surveys), and how will things change in the future?

OMB Creating the Census 1977 categories

US government agencies have long collected demographic data, including information on race and ethnicity. Prior to 1977, there was no comprehensive, official guidance on the best ways to collect these data. In response to the variety of racial and ethnic categories in use across federal agencies at the time, a federal interagency committee was convened and recommended a common set of categories for use across the federal government. That work culminated in what is known as Statistical Policy Directive No. 15 or SPD 15, OMB established five major racial categories for the U.S. Census Bureau to use in its data collection, including “American Indian or Alaskan Native,” “Asian or Pacific Islander,” “Black or African American,” “Hispanic,” and “White.” These categories were designed to provide a consistent and standardized framework for collecting and reporting racial and ethnic data across various federal agencies.

SPD15 also noted that “to provide flexibility, it is preferable to collect data on race and ethnicity separately.” This recommendation was implemented by asking one question about race that consisted of four categories (American Indian or Alaskan Native; Asian or Pacific Islander; Black; and White) and a separate question on ethnicity (Hispanic origin/Not of Hispanic origin).

Census 1997 categories

Over the subsequent 20 years, many began to argue that the five categories (including the ethnicity category) did not accurately capture the diversity of the American population. Thus, beginning with Congressional hearings in 1994, OMB started the process of researching a revised set of guidelines. Those discussions resulted in a new set of recommendations that were published in 1997. This update introduced several key changes:

- First, the “Asian or Pacific Islander” category was divided into two distinct categories: “Asian” and “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.”

- Second, the term “Hispanic” was replaced with “Hispanic or Latino” to encompass a broader range of identities and terminology preferences within this ethnic group.

- Third, the revisions allowed individuals to select more than one racial category, recognizing the increasing prevalence of multiracial identities. (Between the 2010 and 2020 censuses, the number of people who identified with more than one race increased from 9 million people to almost 34 million people.)

All of these changes aimed to provide a more nuanced and inclusive framework for collecting and reporting data on race and ethnicity, enabling better policy-making and resource allocation.

New Race & Ethnicity Categories

Earlier this year, OMB published a final set of revisions to how racial and ethnic data will be collected by US federal data collection agencies. The process started in June 2022 with an Interagency Technical Working Group, which engaged in nearly 100 listening sessions with members of the public and reviewed around 20,000 submitted comments.

After nearly two years of work, OMB is now ready to implement three large revisions to the data collection efforts.

- First, the separate race and ethnicity questions will be combined to a single question. Respondents will be encouraged to select as many options as they wish to capture their identity.

- Second, a new “Middle Eastern or North African” category will be added to the set of options, creating a total of eight possible answers: American Indian or Alaska Native; Asian; Black or African American; Hispanic or Latino; Middle Eastern or North African; Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; White; and Other.

- OMB is also recommending that additional detail beyond these eight possible categories be provided as options for survey respondents, to “ensure further disaggregation in the collection, tabulation, and presentation of data when useful and appropriate.”

How to get involved

You might have been surprised to see nearly 100 listening sessions and 20,000 comments as part of the working group’s process over the past year. Many people and groups are often caught off-guard as to when the federal government (as well as state and local governments) seek input from the public. Unfortunately, there is not a single source that provides all of the notices of government requests for comment or information.

We spoke with several groups that regularly track and participate in these kinds of comment periods, who recommended a few proactive steps you can take to be more engaged and part of the comment process:

- Subscribe to Email Notifications. Many government agencies, including the Census Bureau, offer email subscription services to notify the public about updates, news releases, and requests for comments. Signing up for these services ensures timely notifications.

- Monitor the Federal Register. The Federal Register publishes daily updates on government activities, including requests for information and public comments. Individuals can access it online and even subscribe to receive email notifications about specific topics of interest.

- Visit Agency Websites Regularly. Regularly checking the official websites of agencies such as the Census Bureau, OMB, and other relevant bodies can help individuals stay informed about upcoming requests and deadlines.

- Engage with Professional and Community Organizations. Many professional and community organizations track government announcements and share relevant information with their members. Joining such organizations can provide an additional layer of information.

- Set Up Alerts. Using search engines and news services, individuals can set up alerts for specific keywords related to government requests for information or public comments. This can automate the process of staying informed.

The work of collecting, analyzing, and communicating better, more effective, and more representative data is an ongoing process. That work does not—and should not—be isolated to inside the walls of government agencies and survey collection organizations. Participating in the process–while often difficult and time-consuming—can be an important way to get your voice—and that of your organization or community–heard and ultimately represented in government data.

Jonathan Schwabish is an economist and data visualization specialist at the Urban Institute in Washington, DC.