The Hungarian Marxist, self-made geographer, and economist György Markos (1902–1976) was not the first to introduce ISOTYPE to the Hungarian public, but he was the only one to leave a consistent body of work with pictorial statistics. The ISOTYPE method was not widely used in Hungary, only a couple of sources recognized and praised it as a powerful and useful way of presenting data. That’s why the oeuvre of Markos is unique in Hungary.

During the emigration

Once called the “organizer and propagandist of the Socialist planned economy” (Tatai 1984), after World War II, Markos’ carrier skyrocketed. In 1948, he was appointed as the director of the Economic Geography Department of the Karl Marx University Budapest, he became the press secretary of the Planning Bureau, and he had primary responsibility for the Sovietization of the Hungarian geography. Some things are quite obscure about his life as an illegal communist in the emigration before 1945. What we know, is mostly based on his own words and memories.

According to an interview with him (Sükösd 1975), Markos was born in a religious, reactionary family (his father, Gyula Markos, was the chief editor of the Catholic, anti-semitic pamphlet Herkó Páter), and as a young man, he wanted to be an abstract painter, influenced by the circles of the Hungarian avant-garde poet and painter, Lajos Kassák (1887–1967). In his twenties, he turned to advertising and political graphics during his emigration to Berlin. He designed posters for the German Communist Party, then he continued his agitative work in Paris. In Paris, he connected graphic design with economic statistics, and he worked for newspapers and magazines like L’Humanité, Le Monde and Regards. He describes his interest in graphics in the following way: “I always wanted to paint philosophical content, but I could not make a living out of it. Then I made illustrations for various newspapers and journals, and I arrived to statistical graphs and charts through them. I recognized there was something ideological what can be represented visually: the economic statistics. I tried to extend the economic writings with visualizations. Therefore I met with economics through drawings. During these years I dealt very much with the planned economy of the Soviet Union. I demonstrated its development in the French leftist press through graphs” (Sükösd 1975: 54).

According to Markos, his first significant graphic work was the Les Trusts contre La France (Trusts Against France). In the epilogue of his Hungarian booklet, 50 Families and their Servants, from 1947, he writes that “this work is based on my pre-war work in France about the role in the society of the two hundred French families (Les Trusts contre La France — Trösztök Franciaország ellen. — L’Humanité-kiadás.).” Zoltán Tatai, in his biographical summary of the literary and ideological oeuvre of Markos, writes that his 200 families booklet on the French financial capital was published in 1937 (Tatai 1984), and the Hungarian Telegraph Agency’s biography also gives the 1937 date for the publication. But Markos tells — in the aforementioned interview — that the booklet was published in 1936 and it was a joint work with Pierre Lenoir (Sükösd 1975: 54). The contemporary French reviews put the date 1937 for the publication, but I can’t find Markos’ name amongst the contributors. The authors were the union leader, later Nobel Prize-winner, and labour activist Léon Jouhaux, the Sorbonne-professor Marcel Prenant, the Hungarian-born, Marxist philosopher, Georges Politzer, and the Communist politician, Jacques Duclos. The graphic work was organized by the Swiss engineer, Georges Baehler alias Pierre Lenoir, secretary of the Maison de la Technique of the French Communist Party. The illustrators were the caricaturist Raoul Cabrol and René Dubosc, and we know the pseudonyms of two designers, May and Lépine. Since we don’t know whether Markos used any alias in his emigration, we can’t preclude the possibility that May or Lépine could be Markos. Finally, it is worth noting, in 1946, Baehler published a book on the Swiss cement industry (Zement und Baumaterialen Trust) under the pseudonym Pollux with a series of complex, but non-figurative, network diagrams (Nichols 2018).

There is something more to the mystery. The newspaper L’Humanité published a coloured advertising poster showing the networked connections between French millionaires, right-wing parties, and corporations in 1936 to promote the booklet. This design is similar to the design Markos used in his Hungarian booklet in 1947. At this point, it’s not clear the extent to which, if at all, Markos contributed to the Les Trusts.

After the emigration

Markos arrived back to Hungary after 1937, and in 1939, he started a proto-data journalism column in the newly established conservative newspaper Magyar Nemzet. He ran this “graphic article” series until 1942.

Some graphic articles by György Markos in the newspaper Magyar Nemzet.

His first book, Az orosz ipar fejlődése Nagy Pétertől Sztálinig (The Development of the Russian Industry from Peter the Great to Stalin), was published in 1940, and it contained nearly twenty ISOTYPE-like statistical graphics. The book was considered a breakthrough for the locally-almost unknown Markos. The journalist István Gábor Benedek, in Markos’ necrology, wrote in 1976 that the book was sold out in a couple of weeks and that censorship forbid the reprint in 1941. “Many people asked then, who is György Markos? Those, who did not know his articles in Népszava and Magyar Nemzet, thought it was a pen-name. Others presumed that it was a collective work of the illegal Communist party. They thought there is no one in Hungary who knows so well the Soviet Union (Benedek 1976: 5).”

Some graphics from The Development of the Russian Industry from Peter the Great to Stalin, 1940.

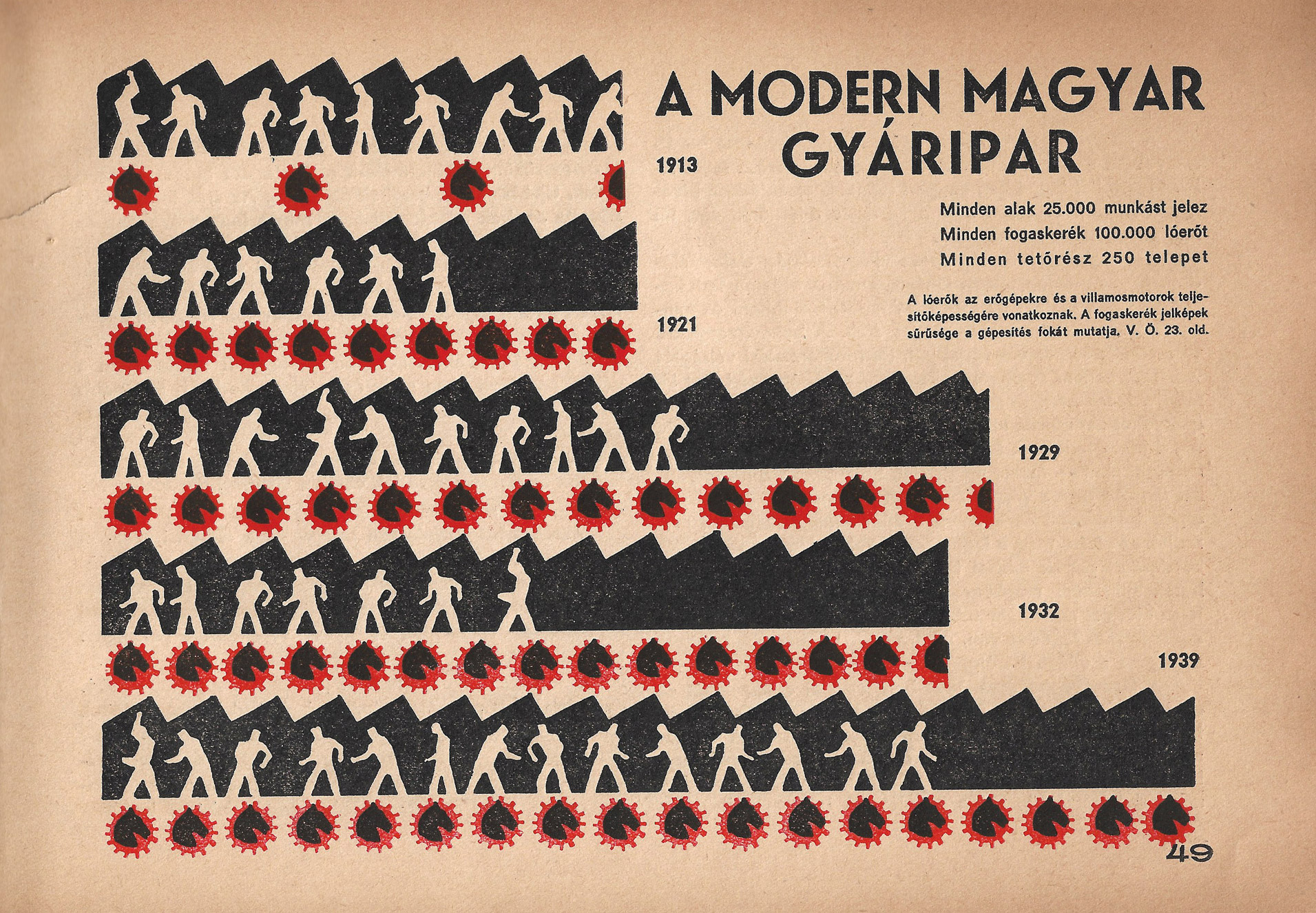

Markos’ ISOTYPE opus was A magyar ipar száz éve (100 years of the Hungarian Industry) from 1942. The album-like layout of the booklet shows thirty full-page ISOTYPE graphics on the different aspects of the industry. The pages are not illustrations of the text, but serve as visual arguments. According to the contemporary press accounts, the book was well received and successful; in one year the third edition was published. Markos advertised the book in newspapers, and he gave presentations countrywide showing the diapositives of the graphics. However, the sociologist Gyula Rézler wrote a mixed review on the book. He pointed out that in some graphs Markos used inaccurate data, or showed the data in a manipulated way. Rézler recognized the album’s value in educating the uneducated and he called it a “penny dreadful of economics, in a noble sense (Rézler 1942: 687).”

After World War II, Markos, as the press secretary of the Planning Bureau, edited a series of agitative and propaganda works using pictorial statistics, like in the A jobb élet útja — 3 éves terv (The Way of a Better Life — the Three Years Plan, 1947), and the Magyarország gazdasága és a hároméves terv (The Economy of Hungary and the Three Years Plan, 1948). His late opus magnum, Magyarország gazdasági földrajza (The Economic Geography of Hungary) was published in 1962, but he did not use the ISOTYPE anymore, only conventional statistical graphs and diagrams.

Markos never mentioned Neurath’s name, nor the ISOTYPE as a source of inspiration.

Works cited

Benedek, István Gábor 1976. Búcsú Markos Györgytől. (Farewell from Markos György). In Magyar Hírlap, 16th July 1976, p. 5

Nichols, Sarah 2018. Pollux’s spears. In “The Costs of Architecture”, special issue, Grey Room 71 (spring 2018), pp. 141–155.

Rézler, Gyula 1942. A magyar ipar száz éve. Könyvismertetés. In Közgazdasági Szemle Vol. LXVI (1942)., pp. 687–688.

Sükösd, Mihály 1975. Markos György. In Valóság Vol. XVIII. №4, pp. 51–62.

Tatai, Zoltán 1984: Markos György, a szocialista tervgazdaság szervezője és propagandistája. (Markos György, the organizer and propagandist of the Socialist planned economy) In Egyetemi Szemle Vol. VI , №1, pp. 131–135.

Attila Bátorfy is a master teacher of journalism and information graphics at the Department of Communication and Media Studies of Eötvös Loránd University Budapest. He is also the head of the first Hungarian visual journalism project ATLO (https://atlo.team/). He is currently working on his PhD-thesis about the early history of information graphics in Hungary.