On a dedicated channel, #dvs-topics-in-data-viz, in the Data Visualization Society Slack, our members discuss questions and issues pertinent to the field of data visualization. Discussion topics rotate every two weeks, and while subjects vary, each one challenges our members to think deeply and holistically about questions that affect the field of data visualization. At the end of each discussion, the moderator recaps some of the insights and observations in a post on Nightingale. You can find all of the other discussions here.

We’re often told that stories, not stats, sell a point. In my data storytelling consultancy, Hillcrest Advisory, I remind clients regularly that our brains are wired for stories. When we hear a story, not only are the language-processing parts of our brain activated, but so too are other areas of our brain that we use when experiencing events from the story. A story, in other words, puts our whole mind to work.

But if storytelling is so important, where does that leave us with respect to data? Typically, stories tell us about an individual experience, but data help us generalize that to a broader phenomenon. Can data visualization, on its own, make a persuasive case — for example, for more funding to support a cause; to encourage people to change a health behavior; or to encourage city council members to vote for a policy?

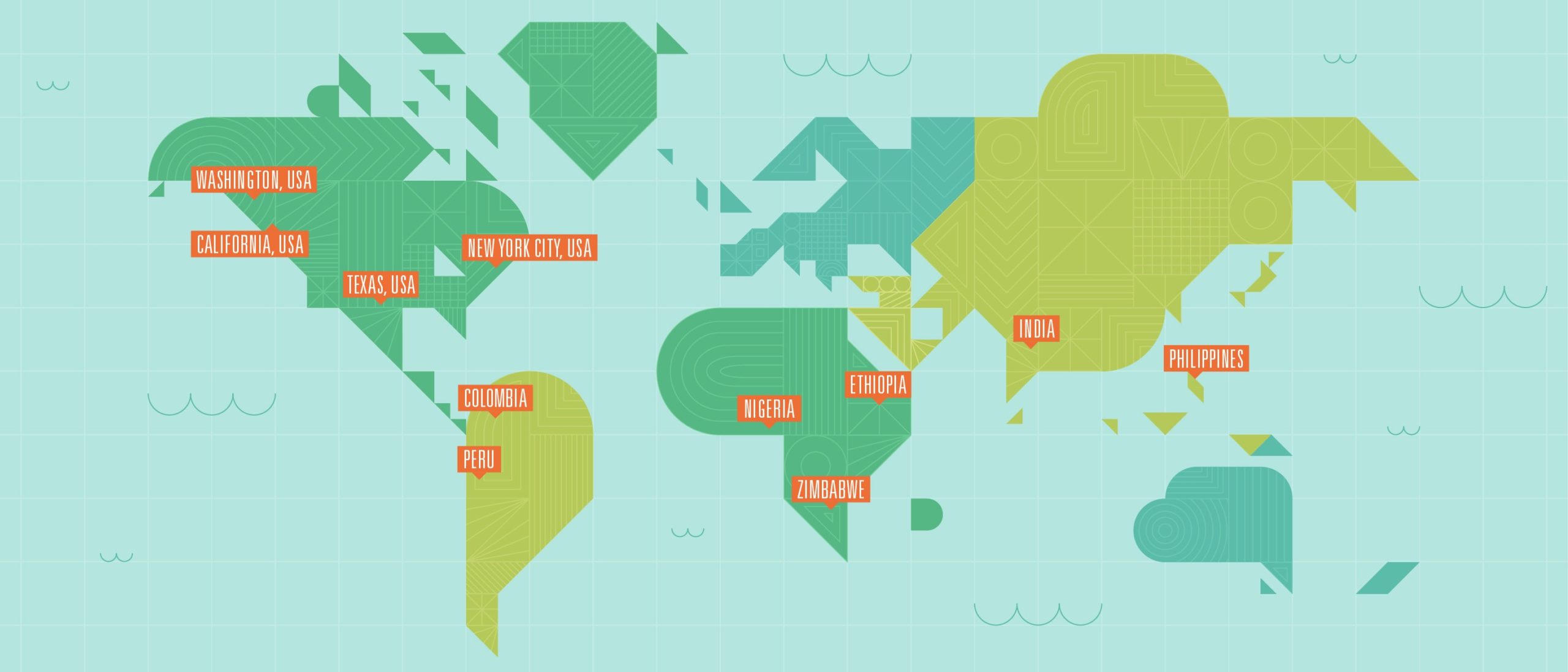

In a discussion forum, we posed this age-old question to the thousands of members of the international Data Visualization Society, asking them to focus, in particular, on the role that data play in local, in-the-trenches work around the globe to improve living conditions. It’s in these community settings where we wanted to know how people leverage data and what specific tactics work.

Far from data visualizations being antiseptic, abstract representations, we learned that graphs and maps, when thoughtfully done, can be visceral, eloquent, and yes, impactful.

In Colombia, for example, Juan Pablo Marin Diaz from Datasketch described how data helped raise awareness, and funds, to combat forced disappearances among young and poor Colombians. In the map above, red shows where people went missing, and green signifies where their bodies were found, often in mass graves.

On a personal level, Bridget Cogley expressed how a data dashboard brought comfort to her friend, Kelly Martin, who was in hospice care and recently passed away. By using a dashboard, they would try out new medications to find the optimal balance between symptom management and alert time. You can read about Kelly’s experience in her blog post, “So long and thanks for all the dashboards.” Bridget, too, blogged about using data as a tool to support hospice care.

Chris Henrick of Google shared an MFA thesis project in which renters in New York City can visit a convenient, step-by-step data tool that helps them find out if their apartment is rent stabilized to prevent high rent increases. Some have used the tool to confront landlords for reimbursement of back rent and to lower future rent.

Amanda Makulec, data visualization lead at Excella, shared how data dashboards for health centers in Zimbabwe help district-level decisions-makers understand where they need to take action, such as when supplies are running low at clinics, and to see how communities are fixing issues (e.g., drilling boreholes to improve water supplies at clinics). S. Anand, who runs the data science/storytelling platform Gramener, described how visualizations helped government officials in India pinpoint where beneficiaries were having difficulties filling out necessary forms, which, when corrected, cut down on error rates and the time taken to complete forms.

And in a county in West Texas, Kate McKerlie described how data visualization helped community organizations catalog what child abuse prevention services were being offered and referred — and where there were gaps. In so doing, the project helped advance local collaboration.

Finally, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington published a data story this month titled, “Precision mapping to end child deaths.” In this visualization, they show how granular data and visualization can work in tandem to “reveal trends and patterns that can help us better understand where to focus efforts to prevent child deaths.” As IHME also says in their story, “Every region has different challenges, and by knowing what the obstacles are at a local level, decision-makers can better strategize how to overcome them.”

To help make that point crystal-clear, IHME showed how visualizing local data in Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Peru can help target interventions in those countries.

The catalog of what works was indeed inspiring, but we also wanted to know what tactics data visualization experts employed to successfully help people leverage data and transform numbers into local change.

These days, there’s a digital arms race in the data visualization world, with news outlets and digital agencies building jaw-droppingly beautiful web creations with which people can interact on computers, phones, and tablets.

But when conducting targeted work at a local level, we learned that such interactives sometimes provide more firepower than is needed. In fact, it can sometimes be awkward in face-to-face meetings to haul out a tablet or a computer to help make a point with a digital display. As Tricia Aung from Johns Hopkins School of Public Health observed, “In my global health experience, data visualizations that are non-digital (printed) can have more weight than digital” tools. She noted that people have “appreciated handouts that they can take back to their office and show others.”

Unisse Chua of De La Salle University in the Philippines commented that “for places that are not fully connected to the Internet, I’d say using non digital would be the best way to get the message out. Some provinces here in the Philippines do not have Internet access.”

Elijah Meeks was advised when presenting to local elected officials to make a map that would be “suitable to be held up on a poster during the city council meeting.” I’ve also seen health departments in California successfully employ data posters at convenings to help elicit input. Attendees are encouraged to add post-it notes to large-scale data displays, in order to share their questions and insights.

Similarly, people talked about printed fact sheets, street murals, data placemat settings at convenings, and stroll-through data galleries that, unlike a linear PowerPoint presentation, allow you to walk to where your interests take you.

Overall, when marshaling data to achieve local change, Data Visualization Society members advised a design thinking approach of walking in the shoes of audiencies you need to reach and integrating their use cases in what you build. Amanda Makulec described this as understanding end-users “needs and experiences.” She said, “Ultimately, if the goal is for the local organization or audience to own the product (as in, use it in their day-to-day work), customizing and tailoring to make it personal to them is so important.”

In other words, if you don’t ask what users need, you won’t know, and you’ll be flying blind with the data product you’re building — perhaps, for example, by overbuilding with an interactive that doesn’t match local use cases. It’s no surprise then that, when marshaling data to advance local change, data visualization practitioners were strong advocates of talking to end-users, so that you build durable data tools that respond to real-life scenarios.

Finally, a number of respondents noted how it’s not a question of data or stories; the two elements needn’t be siloed from each other when imparting information to make progress on social issues. Chris Henrick advocated for adding what he termed “the human element” to data visualizations — such as photos, personal narratives, and audio. By painting data on this broader canvas, he said, we’ll make numbers “more relatable, and engage audiences who aren’t as familiar or comfortable with abstract data, charts, and fancy visualizations.”

So in the end, we learned from Data Visualization Society members that there isn’t an either/or choice to be made between data and stories. In the social sector, we need to leverage both to make compelling cases that can advance local change.

Andy Krackov runs a consultancy, Hillcrest Advisory, to help social sector organizations in California and elsewhere communicate and tell stories with data. A decade ago, when he was a program officer at the California Health Care Foundation, he worked closely with government agencies in Sacramento and Washington, D.C. to open up public access to their data.