Every December, New Yorkers face a unique dilemma: the holiday tipping tradition. In buildings with doormen, supers (live-in maintenance staff), and porters (cleaning and maintenance workers), residents are expected to hand out year-end tips to show gratitude to the staff who keep the building running smoothly.

For some, this is a cherished tradition; for others, it’s a source of stress. How much is enough? Too much? And what does it say about you if you skip it altogether?

Holiday tipping is more than a financial transaction—it’s a cultural ritual steeped in classism, social expectations, and personal values. For the data-curious and analytical souls, it offers an intriguing case study. While numeric data tells us the what—how much people tip—sentiment and context reveal the why.

Let’s explore what happens when we combine quantitative analysis, emotional data, and contextual inquiry to make sense of this tradition.

The numbers: what does the numeric data tell?

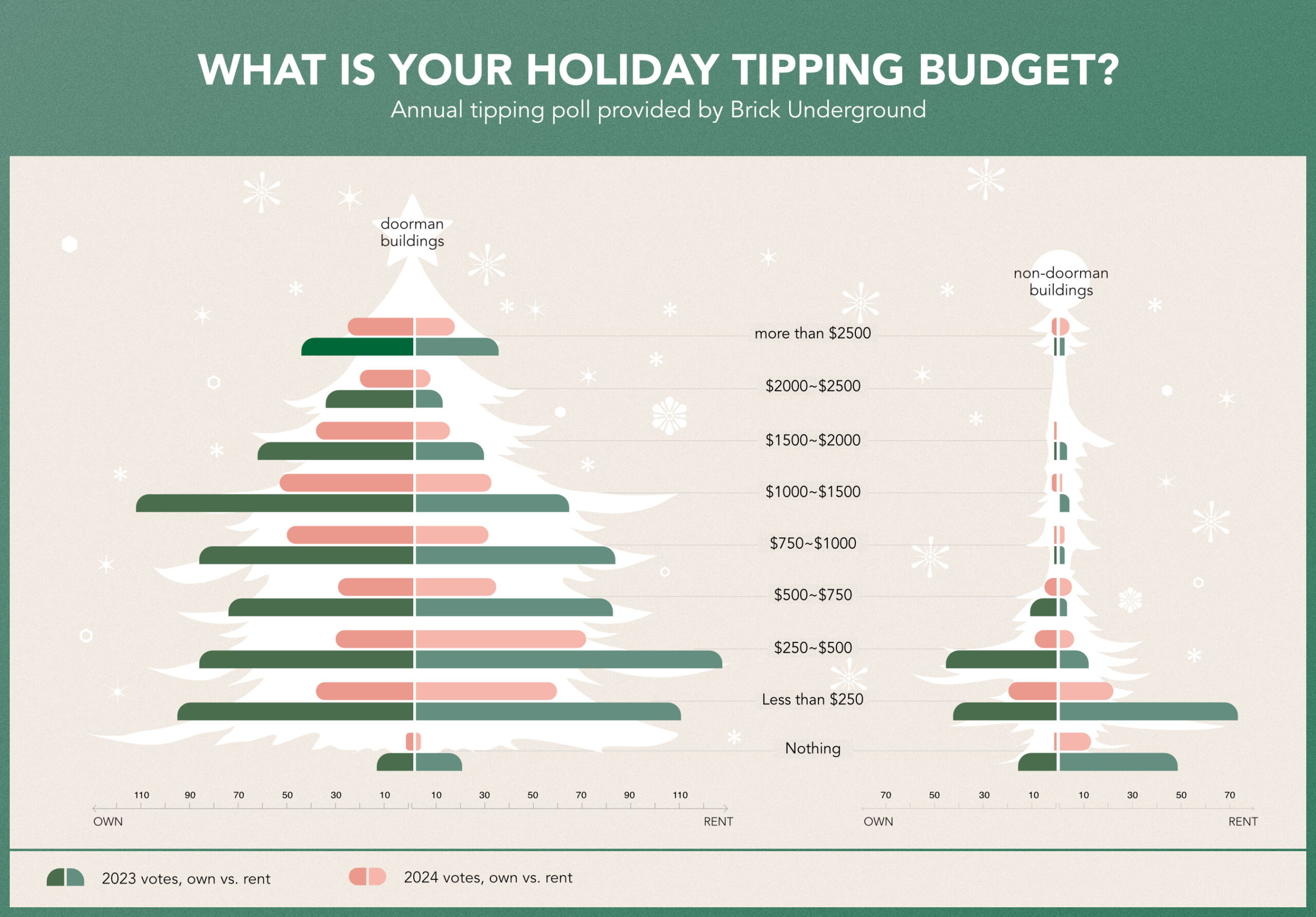

Data from Brick Underground’s annual tipping polls provides a snapshot of residents’ practices. The poll questions were intentionally brief to encourage participation, capturing only total tipping budgets per household. Factors like age, income, household size, building staff size, or rent-control status were omitted. While this limits precision, the data offers a useful baseline.

One clear pattern is the difference between doorman and non-doorman buildings. In both 2023 and 2024 polls, respondents from doorman buildings vastly outnumbered those from non-doorman buildings—by a 4:1 ratio in 2023 and 6:1 in 2024. Unsurprisingly, doorman building residents budget significantly more for tipping, often between $500 and $1,500. In non-doorman buildings, most respondents tip $250 or less.

Another distinction emerges between renters and owners. Renters generally report lower tipping budgets, including those in New York’s famed rent-controlled apartments. In both years, owners tended to budget more generously across all categories.

While numbers provide a baseline, they don’t capture the emotional complexities—gratitude, guilt, or social pressure—that influence tipping decisions.

The sentiments: what can we learn from feelings?

West Side Rag, a neighborhood newspaper, published “Confessions of Upper West Side Holiday Tippers,” sparking a heated conversation in the comments section. The comments provided a consistent sample for analyzing sentiments within a specific community.

After categorizing 39 emotionally charged comments, I identified five main sentiments:

? I’m grateful and happy to give.

“Come on, guys! They treat us like gold. What’s that worth? It is what enables us to live the way we live in New York, a city requiring a lot of help to feel comfortable. These people make our lives so much easier and, on Christmas, why not make their lives easier?”

? I tip like a boss.

“Before I stuff envelopes with cash, I take into consideration each staff member’s performance and how my financial year played out. As I hand deliver each envelope I express my gratitude or disappointment.”

? Just tell me how much.

“This entire thing is just confusing. Why make everyone guess?”

? I disapprove of it but tip anyway.

“I am totally against tipping building personnel but I give anyway. I am not made of money. There are plenty of people working in jobs that pay less and do not have benefits and probably don’t get holiday tips. I would rather donate to a charity.”

? I despise this “tradition”.

“Seriously not one single person thought to get rid of compulsory tipping at the end of year? I find this ‘tradition’ completely unreasonable. It is basically coercion.”

Generating a simple pivot table from the comments revealed a surprising insight: positivity dominated the dataset. Combining “? I’m grateful” and “? I tip like a boss,” 24 out of 39 commenters willingly tipped their staff. Despite angry comments being disproportionately more memorable, only four expressed outright resentment (?).

This exercise highlighted my own negativity bias. Like many, I was drawn to angry comments that echoed my frustrations, such as:

“Who would give $500 to two people who you say do NOTHING? Madness!”

Initially, this quote reinforced my view that tipping is a band-aid for systemic inequality. However, summarizing the data made me realize how much positivity I had overlooked.

Emotional analysis requires rich context

Sentiments don’t exist in a vacuum. Context is crucial to understanding them. For example, long-time residents often expressed comfort and generosity toward the tradition, while younger generations and newcomers of New York were more likely to question its validity.

To deepen my understanding, I interviewed five people with different life circumstances. Their tipping decisions reflected not just their feelings about holiday tipping but also their upbringing, social values, and financial realities. These conversations, paired with historical inquiry on tipping and apartment living in New York, painted a fuller picture of why this tradition persists.

Quantitative analysis provides numbers, but qualitative inquiry reveals the humanity behind them. Together, they create a nuanced understanding of complex issues.

So, what did I do this holiday?

This was my fourth year deciding on holiday tipping. Initially, I was in the “? I disapprove of it but do it anyway” camp, resenting the expectation while feeling guilty for the staff. But this year, through research and reflection, I reframed my relationship with tipping.

I realized that I felt disconnected from the staff, which made the tipping gesture uncomfortable to me. It’s not just because I rarely asked for favors but because I had always handed my tips to the managing office anonymously. Inspired by my findings, this year I wrote personal notes, handed the envelopes directly to each staff member, and looked them in the eye as I said, “Thank you.”

This is our super. Seeing his office adorned with holiday cards from residents, I let go of my analytical mind and felt my heart for once. My thoughts on inequality had made me overly rigid, feeling powerless, and I had forgotten that small gestures of kindness could have the power to make a difference.

What this means to data professionals

We increasingly rely on numbers and charts to describe the world, but data alone doesn’t lead to better decisions—understanding does. Many of us were hired to crunch numbers and tell visually appealing stories, often based on predefined viewpoints. But I think our higher purpose is to connect data to the human experience, so that we can make better, more thoughtful decisions.

Quantitative data is easier to visualize, but complex social issues require both quantitative and qualitative analysis. Qualitative data adds depth by uncovering the motivations, context, and emotions behind behaviors. While tools like LLMs can assist in processing this information, we should be aware of their limitations.

For example, when I read a commenter saying, “We have 29 employees, and I give $3,000 and feel cheap!” my initial reaction was, “This must be a humble brag!” Only after speaking to higher-income residents did I realize the commenter might genuinely feel guilt. Accurately interpreting such statements requires context, emotion, and human reflection—things no machine can fully replicate.

LLMs and analytics help us process the “what,” but it is our uniquely human capacity to reflect, empathize, and feel that gives meaning to the “why.” As data visualization professionals, our role is not just to visualize data but to bridge the gap between logic and emotion, quantifiable and unquantifiable, mind and heart.At the end of the day, the real question isn’t just, “What does the data show?” but, “What does it mean to you, and how does it make you feel?” Only by connecting data to the humanity within us can we make thoughtful and impactful decisions.

Shanfan Huang

Shanfan Huang is a designer, illustrator, and writer passionate about storytelling in all its forms. From picture books and comics to information design, interaction design, and loop animations, she explores how meaning is derived through visual symbolism. She shares her thoughts and discoveries in her Substack newsletter, Picture, Text, and Numbers. When she’s not crafting visual narratives, you can find her sharing snippets of doodles and half-baked ideas on Instagram