We used to call “unicorns” people who are skilled in seemingly opposed areas, such as data, design, and code; or math, business, and technology. However, even a magical creature is not enough to describe the work of Lalena Fisher.

Lalena Fisher is a multi-talented creative with a diverse background in journalism, painting, graphic design, and music. She has designed for shows like Blue’s Clues and The Wonder Pets, created information graphics for The New York Times, and written and illustrated children’s books. Lalena also has a career in music, including a mother-and-daughter heavy rock duo, The Mothermold. Her work reflects her fascination with dichotomies in life and her desire to challenge them. Through her art, she explores themes related to family, gender, strength, and dominance, shining a light on the absurdity of assumptions about all dualities.

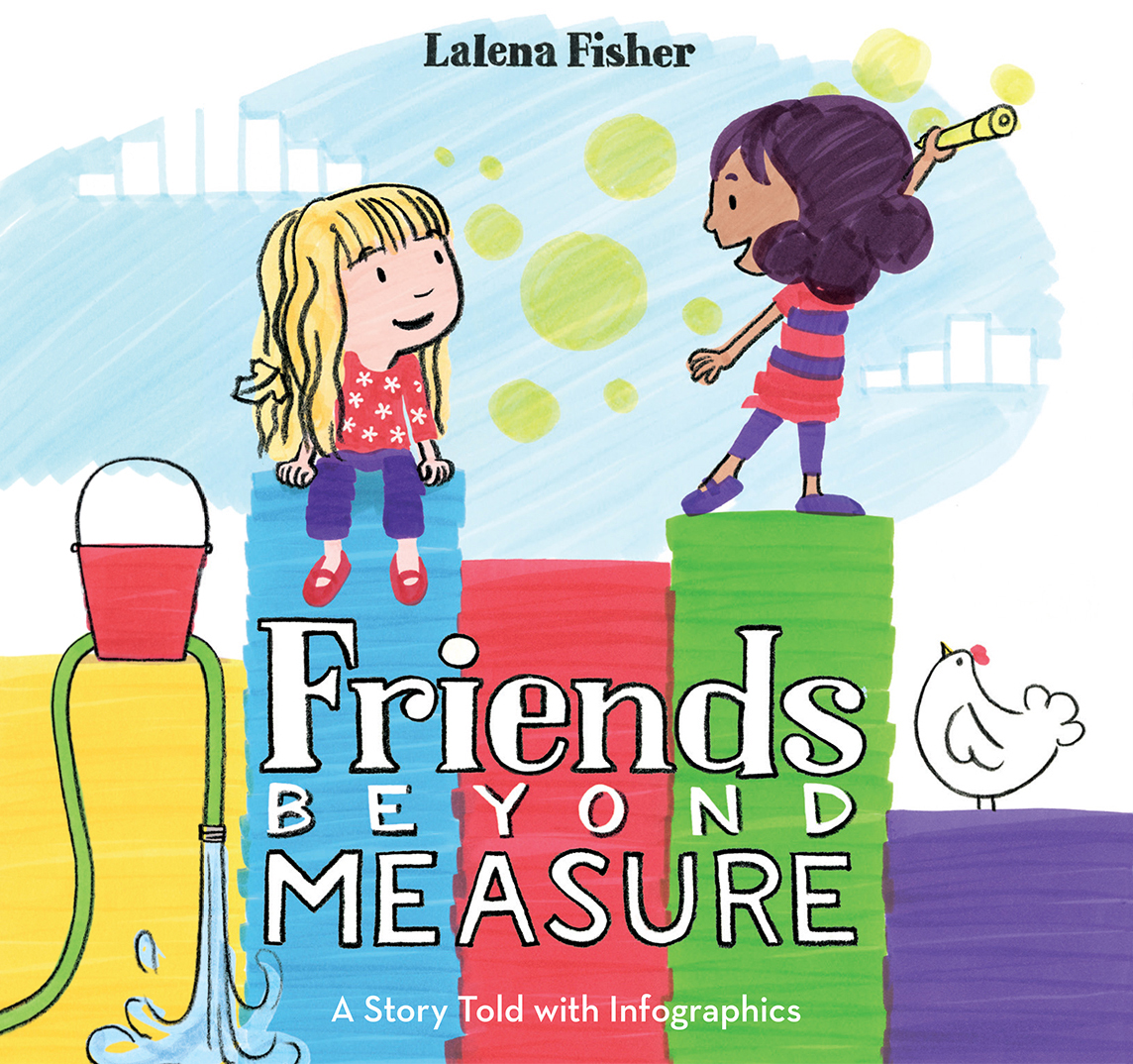

Lalena’s latest children’s book, Friends Beyond Measure (HarperKIDS), combines her expertise in illustration and infographics to tell a heartwarming story of friendship. The book follows the journey of two friends, Ana and Harwin, and explores how their bond is tested when a major change in their lives threatens to shake things up.

In this interview, we have a chance to learn more about Lalena’s creative process, her inspirations, and how she brings together seemingly disparate fields to create something truly unique.

Where did the inspiration to write a children’s book through data visualization come from?

Designing for Blue’s Clues, a show for preschoolers, sparked my desire to create my own children’s stories. After a lot of learning and drafting, I had a book ready to pitch to publishers. But that book was not Friends Beyond Measure! It was a lyrical bedtime book. And in the pitching process, someone looked into my background and commented that I might also consider creating a children’s book with infographics. I thought this was an interesting idea.

So I checked out all the children’s books I could find that had information graphics. I saw a number of beautiful nonfiction ones, like Animals By the Numbers, and Professor Astro Cat’s Atomic Adventure. No point in trying to top those! I wanted to do something different—something that would stand out.

I wondered if charts and graphs and maps could be used to tell a children’s story — one with an emotional arc. This seemed like a fun challenge. I had never seen this before. My good friend was moving across the world at the time, and I was quite sad about it; so I tapped into my own feelings for Friends Beyond Measure.

The book’s proposal is an original idea, and we can see it was executed with a lot of care on how much a child between the ages of four and eight would understand. What were the editor’s inputs on how this would be received/perceived by children?

The feedback I got from my HarperCollins team, who were wonderful, had mainly to do with narrative arc and story points. There was one chart they thought would be hard for kids to understand—it was a scatter plot. I could see how it might be a bit confusing to a child, so I replaced it with the set of “parts to a whole” charts—a type that I didn’t previously include, but that is very useful and common. So it was a good change.

A common subject in kids’ literature is to surround, in the most playful way, subjects that are hard for the infant brain to handle—like feelings, body changes, being far from a loved one. As a second issue, your book also tackles data education. In a world that seems to ignore the need for data literacy, how do you see the potential of your book in being the first contact of children with this universe, with this skill?

I hope Friends Beyond Measure sparks conversations with kids and grown-ups about visual communication as well as emotions. And about how people close to each other can have big differences.

Visual thinking comes naturally to a lot of kids — it did to me (though I was also very verbal and a voracious reader). Dr. Temple Grandin has been bringing a lot of attention to this in recent years, pointing out that we can’t afford to neglect these skills in kids; we must cultivate them. It could even be that some kids will understand the book more intuitively than their grown-ups, who for their part can, while reading the book with their kiddos, ease into more comfort and enjoyment with graphs, maps, and diagrams. And feelings too!

Your background is in journalism, with a Master of Fine Arts degree and a career in music. You were also a contributing graphics editor for The New York Times, designing diagrams and charts for news and for the science section. How did science and data become one of your interests and part of your work?

Artists and scientists have traits in common: curiosity and imagination.

As a small child, when I asked how babies are made and grow, my mom wanted me to know the truth. And growing up, I was surrounded by recurring family illness, so the language of medical science became second nature. My family spent a lot of time at the Gulf of Mexico, and marine biology captured my imagination; the oceans hold so many mind-boggling creatures. And I loved tracking hurricanes, using maps printed on grocery bags during hurricane season.

I was not a kid who liked arithmetic; it was boring and tedious. That’s why it’s important to me to help kids see more of the fun in math. I did love drawing, and I loved organizing things. That’s the connection I make now, with my enjoyment of information graphics. And in middle school, I did a 180-turnaround in math when I started algebra; I had a great teacher, for one thing. And in algebra and the other higher maths, you basically are organizing and simplifying information, which I find almost comforting to do!

Can you describe your experience with handling data to create infographics? What are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced in this process and how have you overcome them?

In my earlier years at the Times, I often created science graphics, and I enjoyed drawing diagrams of organisms and systems. Appreciation of numeric data did not come as naturally; I learned how to work with it over time and how to have fun transforming it into visuals. And I now relish the opportunity to transform numbers into a visual design.

At the beginning of the pandemic, when I rejoined the Times team, my task was mainly to visualize Covid-19 data for the “Morning Newsletter.” I was examining the immense spreadsheets of cases and deaths from every county in the United States, and every country in the world, every day—it was daunting at first! But I learned from my amazing and patient colleagues how to manage it, and crunch it in all these different ways, and I grew to feel very much at home in those spreadsheets.

In your artist statement, you say that you make art that “forces dualities together, exposing the absurdity of assumptions about strength and dominance.” This contrast seems to be present in many ways in all of your work (a mother-daughter punk rock band, for example). Motherhood and the female family presence is also a strong influence. How do you see these contrasts in the experience of raising a child?

I love this question! In motherhood, I feel I am regularly swinging back and forth between asserting dominance and showing vulnerability. One way to manage that is to laugh at oneself sometimes—like I am in our song and music video for “Because I Said So”! You need your child to obey you unquestioningly sometimes, to keep them safe. But at the same time, in order for them to grow into an adult who can adapt to change and maintain strong relationships, we have to be able to show we can admit when we’re wrong, or even just don’t know what to do.

Do you see data visualization as one of these dualities? Considering that art and logic go hand in hand in this area—two things absurdly assumed as, respectively, female and male.

Some might say data visualization is a counterpoint to more organic, visceral forms of expression. But as with a lot of apparent dichotomies, I think they aren’t oppositional at all. Illustrating data is a form of communication. Does data stand in contrast to, say, feelings? One might characterize data as “facts” or “truth.” But feelings are just as real, and just as truthful. This idea is exactly what I was trying to tap into with Friends Beyond Measure.

If we are making a Venn diagram between art and data (as the main character in your book loves to do) who would be your inspiration in each one of the sections (art, data, and the intersection between them)?

Ha ha! This is great. Okay, let’s see…

Ana Paula Lamberti Bertol

Ana Bertol is a physicist who is passionate about listening to problems and understanding them deeply. She works as Data Project Leader at Odd Data & Design Studio, where she translates Science and Technology to Design (and vice versa), bridging logic and creativity. She sees everything as functions and charts, whether it's her daughter's sleep pattern, the best way to fry an egg, or the organization of books in the library.