Dr. Chris Mullen’s drive to collect and share information has created a fascinating archive with a focus on Fortunes Magazine and the history of visual communication

Less than two years ago, I found myself on a website with abstract links and that featured the quote “IT BEGGARS BELIEF…” on its homepage. The ellipsis suggested to me that someone was about to elaborate. How right I was.

I came to learn that the site is called The Visual Telling of Stories and it’s the brainchild of Dr. Chris Mullen.

Memory theatre

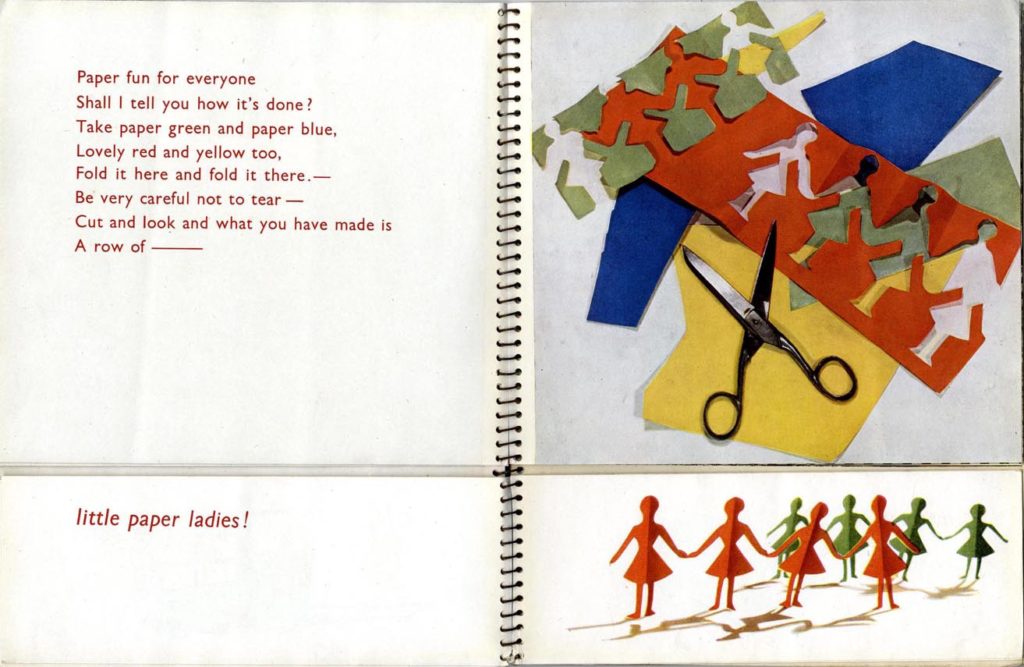

To call The Visual Telling of Stories an archive doesn’t do justice to the crafty mind that has assembled it. To call it a game would imply that it has rules. After a lot of thinking I’ve come to the conclusion that the scope of the project and its deliberate artiness is actually a decent approximation of Mullen’s own mind. Sometimes carefully documented, sometimes hastily jotted; blind hyperlinks are common, rarely labeled, and always lead to brilliantly unexpected but related information.

The site is more like a memory than a library: a mixture of academic clippings, magazine advertising, personal reflections, correspondence with art directors, illustrators, and friends, cartoons, old books, and diagrams from every subject and time period. Too personal to be academic and too rigorous to be a diary, it’s a living example of what it is to perpetually learn.

After returning to the site over and over again, I decided to contact Chris to learn more. We’ve been in contact for a few months now and I even had the pleasure of visiting him and his wife at their home in Brighton, UK.

What is The Visual Telling of Stories?

I asked Chris to give some context into how this sprawling work began and why it continues today:

Simply put, The Visual Telling of Stories site (hereafter the VTS) was started as a personal initiative in support of the new Masters Course in Narrative and the Sequential at the University of Brighton in 1989. Imagine concentric circles. At the core is every lecture and seminar given, with film notes and reports. Then come key images and documents. Then an outer ring of images that fill in the gaps…Our students were part-time, most were working professionals and many lived hours of traveling away from Brighton. VTS kept everybody in touch.

I moved to Brighton to enjoy the possibilities and I just kept adding more circles: whole illustrated books from my own collection (Macao et Cosmage 1919); dialogues with artists and designers (Nigel Henderson of the Independent Group, and Tom Eckersley, poster designer).

I visited the Rochester Institute of Technology in 1982 and had been impressed by R. Roger Remington’s initiative of attracting graphic material and committing scans to a laser disk. To devise a taxonomy that would accommodate any image found, it seemed to me the height of wonderment. Meeting Jim Fraser at the Fairleigh Dickinson University Library, who hosted the Archives of the American Outdoor Advertising Association, was another inspiration, “Do you want to be in the Fast Lane?” he asked. “Oh yes,” I said.

In 1994, Mullen started writing HTML as a way of getting around institutional barriers. The internet let Mullen directly interface with current (and past) students and continually document and his lectures and ideas. He continues:

With so many concentric circles, paths of navigation had to be found. What were they to be? Or rather, what was the metaphor for the unfolding of data? I found a digital culture in the UK torn between librarianship and the comic strip… the emphasis was on the visual, that complex multi-layered propositions might be contained in an image flow with the minimum of text (a la Feynman Diagrams). From that date, I have worked a minimum of four hours a day adding circles and using my own library.

The collection that is The Visual Telling of Stories

I had the opportunity to visit Chris and Oriole one bright September morning. After looking at so many pages, with blissful hours lost in the maze of the VTS, it was a real joy to visit Chris in his home.

I had some suspicion that their home would be filled with a lifetime of art and books — both of which I found — but Mullen’s fascination wasn’t oppressive. A lightness permeated the house and charitable goodwill filled my visit. His library was loosely arranged and filled with a variety of objects:

Ninety percent of VTS is from my [magazine and book] collection; illustrated auction catalogues; gallery catalogues long forgotten of neglected artists; trade catalogues; gramophone needle tins; book matches, all embedded in my very own Memory Theatre for instant retrieval (well almost). If I was to take Visualisation seriously, I had to get my own materials. Thank heavens for a huge garage never to receive a car.

As we walked a few steps across his delightful flower-filled garden into the garage, I had a feeling we would find some kind of treasure. On entering, Chris pointed to several large shelves to his right, “there it is.”

The importance of Fortune

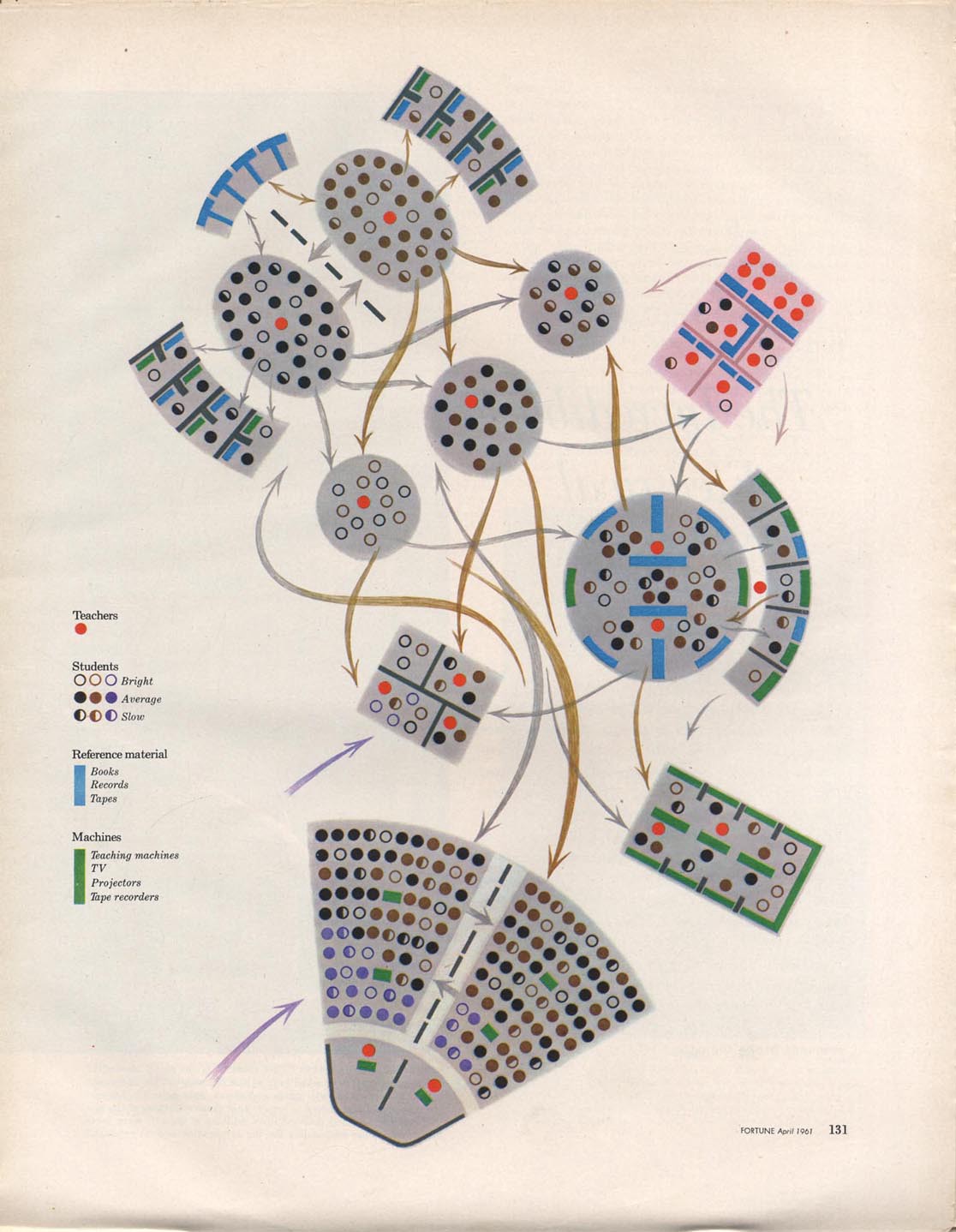

The image that originally brought me to the VTS was from Fortune magazine. While Fortune is commonly known to be an important midcentury American design resource, it somehow hasn’t been remembered or acknowledged in the digital age. Hastily scanned versions have only just appeared on Archive.org. There is not a published compendium of Fortune artwork, and the names of its art directors and central designers are not common outside of the occasional essay by design historians. For example, one of its visionaries was art director Will Burtin (1945-49), who became a key figure in midcentury corporate design. Despite Burtin’s importance to midcentury design, his name and others just don’t carry weight anymore.

I’d argue that the deep connection between American business, data, and its visualization, might easily be traced to the widespread influence of Fortune Magazine in its prime years. It is a treasure trove of data visualization and information design and few people understand it like Mullen.

Mullen’s archive of Fortune is a big part of The Visual Telling of Stories. His vast understanding of the American information-design resource is so deep that it reveals his personal connection to the publication, its mission, and the artists that created it. Chris recounted his first experience with the magazine at a late-night second-hand shop in the mid-1970s:

I had never seen such a beautiful publication as that mint copy of Fortune, April 1959. I filled the car with over a hundred at 20 pence each. At every roundabout, the piles slid over our children riding in the back seat. To this day my daughter associates the smell of Fortune with a sudden dimming of the daylight.

Phoning on my return, it seemed a container with three runs of Fortune from 1930 to 1960 (duplicates from American public libraries) was available very cheaply. There was one run for my fellow enthusiast Phil Beard, one for tear sheets, and the third run for keeps.

His website boasts a funny detail for anyone who’s tried to present this stuff: No gutters appeared in my teaching imagery, just the majesty of the pages, single and double.

And those articles and illustrations (now housed in the online portfolios and in his garage) are indeed majestic. Gallery after gallery, page after page of incredible diagrams, illustrations, and charts, all scanned in high-res quality, organized by illustrator, often with publication date and issue. We see not only the highlights from Fortune, but full articles featuring all kinds of businesses from radioisotopes to air cargo. The way Fortune covered American business was markedly different from any other magazine.

Fortune was on subscription, delivered in custom-made packaging that would have withstood a hand grenade, it was a dollar when others were 25 cents. It was immaculately printed on antique laid paper, quickly establishing visual aspects of the American economy with portfolios commissioned from illustrators as well as photographers. Artists previously known as gallery types were sent off on location (such as Philip Guston), or given diagrams of telecommunications or atomic testing.

Fortune didn’t just present articles on midcentury businesses, they instead visually explained a new era of American ingenuity as envisioned by the leading practitioners of modernist design. To Mullen, “Fortune explained the great intangibles to its readership.” The below spreads matched leading designers with industries they couldn’t have dreamed they would be working on, but somehow it all worked so well.

Mullens and his colleague Phil Beard hatched an idea to present an exhibition of pages from their collection. In addition to digesting, scanning, and archiving countless issues of Fortune, Mullen also began to correspond with many of its artists and designers to learn more about their personal stories. Their letters have all been scanned on the site, and they are touching examples of the quickly established bond of professional fraternity. “We wrote hundreds of letters to named Fortune staff and commissioned artists. Only one artist failed to respond, and I think he was dead.”

We exhibited ‘Fortune’s America’ at the University of East Anglia and at Rochester (NY) with the delightful and inspiring R. Roger Remington. I had brought the show over in a carrier bag of tear sheets. The show, the letters, and the life’s work of the illustrator designer Tony Petruccelli are all on the VTS website, and more is still being added.

Visits to remarkable places

But Fortune is only one aspect of the VTS. There are collections of original isotypes, scanned issues of BLAST, countless advertisements, cartoons, and illustrations organized by subject matter (“Sex” is an especially provocative category), and literally thousands more.

It’s taken me weeks to write this article because every time I open the site I find more and more amazing content. It’s impossible not to be surprised by what you’ll find and I rarely stumble on the same content twice. Even though Mullen knows it’s a huge amount of information, he playfully toys with his audience.

Back at his house again, Mullen says to me with a raised eyebrow “Have you found Grammercy Park yet?” His wife Oriole lets out a chuckle.

A legacy of generosity

Initially, the internet was a place for Mullen to teach his students, but as Mullen has built the VTS it has evolved over decades into something more holistic. As the internet is often decried as a place of trolls and hostility, legions of people are archiving many aspects of cultural history, there for the finding.

I was pleased to hear that I was the latest in a sequence of guests spanning many years of pilgrimage to meet Mullen. Designers, researchers, and interested parties have all found the VTS, and his good nature has pulled many of them to Brighton for a visit. It’s comforting (for me at least) to know that there is a network of people that are exploring the history of information design. Visiting the VTS should be considered as a central resource for this, comparable to the great libraries of the world. While less documented, the VTS is certainly more fun.

Chris Mullen’s life’s work of teaching the clever ways humans communicate visually is a treasure. What started as a teaching aid soon became something less defined and all-encompassing. It is a gift that artists and designers should collectively embrace, uphold, and celebrate. I urge anyone to take some time wandering around its pages. You will not know what is around the corner, but what you’ll find is truly wonderful.

Here it is. Go get lost: https://www.fulltable.com/vts/index2.htm

Special thanks to Chris and Oriole Mullen for being so wonderful, and Clare Harvey for editing.

Jason Forrest is a data visualization designer and writer living in New York City. He is the director of the Data Visualization Lab for McKinsey and Company. In addition to being on the board of directors of the Data Visualization Society, he is also the editor-in-chief of Nightingale: The Journal of the Data Visualization Society. He writes about the intersection of culture and information design and is currently working on a book about pictorial statistics.