I recently learned that my 2021 article about why I no longer use box plots is now the second-most-read article in Nightingale’s history🤯 (or, at least, since Nightingale moved to its current hosting platform). What do you do when you have a hit on your hands? Milk it, baby, by writing a sequel 😎

When that article came out, I got a lot of comments and replies. Like, a lot a lot. Like, I spent three days responding to them. There were all sorts of comments, of course, but there were definitely common themes. This article summarizes the most common replies that I received, along with how I responded to each, making it very much a sequel to the original article, just with several hundred new coauthors. Well, uncredited coauthors🤷

The majority of the replies that I received expressed some form of agreement, with chart creators thanking me for helping them understand why their box plots flopped with audiences or for making them aware of alternatives like strip plots and distribution heatmaps. You’re welcome!

There were, however, also plenty of thoughtful objections and counterarguments, and I’ll be focusing on those because reading about people agreeing with one another is pleasant and boring.

Alrighty, then. First up is…

“This [example box plot] is useful! I can clearly see [insight, insight, insight, etc.]!”

I wasn’t suggesting that box plots aren’t useful. Obviously, they can show useful insights. I was suggesting that simpler chart types like strip plots and distribution heatmaps can show all the same insights that box plots can, but are easier to understand, less prone to misinterpretation, and don’t hide potentially important information. I wasn’t claiming that box plots are useless, just that, when compared with other distribution chart types, box plots have some significant disadvantages and no identifiable advantages, so it might make sense to use other chart types instead.

To dispute the claim that I was making, then, you’d need to show the same dataset as a box plot, strip plot and distribution heatmap, and then identify specific insights that are clearer in the box plot than in those simpler chart types. Many people did send me box plots, but most didn’t include strip plots or distribution heatmaps of the same data. This made it difficult or impossible to see if the insights that they pointed out in their box plot would have been just as clear in those simpler chart types. None of these responses, then, actually addressed the claim that I was making.

Some people did step up, however, such as Sergio Garcia Mora, who showed the same dataset in a variety of chart types in this fantastic article:

This is what Sergio wrote about the box plot version:

“What I like about this visualization is that we can see the distribution of the salaries by the size of the halves of the boxes. Let’s take for instance the Head position. The medians are similar, but in the case of women, the bottom half of the box is larger, so that means that the range of salaries for women is broader. That tells us that there are women in Head position with salaries far below the median.

The opposite happens with male professionals in the Head position. The top half of the box is larger meaning that there are men in the Head position with salaries far above the median.”

To my eye, anyway, all of these insights are at least as clear in the jittered strip plot version. Plus, I could see several insights in the strip plot that weren’t visible in the box plot, such as the fact that there are fewer employees in the more senior roles, that no Managers make between about AR$85K and AR$110K, etc.

There might be box plots out there that show insights that aren’t as clear in simpler chart types, but I have yet to come across a single one. If you have one, send it to me! (Just make sure to include a well-designed strip plot and distribution heatmap showing the same data, s’il vous plait.)

“Box plots are useful because they show quartiles.”

Quartiles aren’t insights, they’re just features of charts that allow readers to spot actual insights like, “The salaries in Company A are more dispersed than the salaries in Company B, which suggests that there’s more room to move up in Company A.” That’s an insight, and you almost never need quartiles to spot those.

Saying that “box plots are a useful way to show quartiles” is like saying that “distribution heatmaps are a useful way to show the bins/intervals that the values fall into.” These aren’t insights, they’re chart features that allow readers to spot insights. What ultimately matters is how clearly each chart type shows insights, not the specific mechanisms that are used to make those insights clear.

Having said that, there are rare cases when quartiles have some special meaning. For example, maybe a company has decided to lay off the middle 50% of its employees based on salaries (which would be weird but, like I said, these are rare cases). Even in a scenario like that, though, interquartile ranges (i.e., the middle 50% of values) could be shown in strip plots and distribution heatmaps, which would still be easier to read and clearer than box plots:

Like I said, though, it would be very rare to have to do this in practice because, in the vast majority of charts, quartiles (or quintiles, terciles, etc.) have no special meaning and aren’t needed in order to spot useful insights.

“Box plots make outliers easy to spot.”

That’s true, but outliers are just as easy to spot in simpler chart types. For example, in the “salaries by role” jittered strip plot that I showed earlier, the outliers are pretty obvious—they’re the dots that are far away from the main cluster of dots. You could make outliers in a strip plot even more obvious by highlighting those dots but this seems unnecessary; their location away from the other dots already identifies them as outliers.

Outliers can also be added to distribution heatmaps, similar to how they’re added to box plots:

“Box plots work well when there are many distributions to show because they look less visually busy.”

Some people sent me box plots with many sets of values, like the one below, arguing that other chart types would be even busier looking:

It’s true that strip plots can look quite busy when there are many sets of values in a chart, but distribution heatmaps are well-suited to these situations:

Personally, I find that the graphics in a distribution heatmap actually are less visually busy than boxes and whiskers, but this is probably subjective.

“Why not combine box plots and strip plots to get the best of both worlds?”

Some people suggested combining strip plots and box plots, like this:

Yes, you could do this, but the question then becomes: which specific insights are the boxes making clear that wouldn’t have been clear in the strip plot on its own—perhaps with the medians added, since they’re often relevant? I can’t see any such insights, so the boxes just add complexity without adding any value, IMHO. Basically, I don’t think this is a “best of both worlds” solution because there’s no “second world” in this case, i.e. insights that box plots would show that wouldn’t already be clear in strip plots.

“Sure, box plots don’t work well with multimodal distributions, but they shouldn’t be used to show data like that in the first place.”

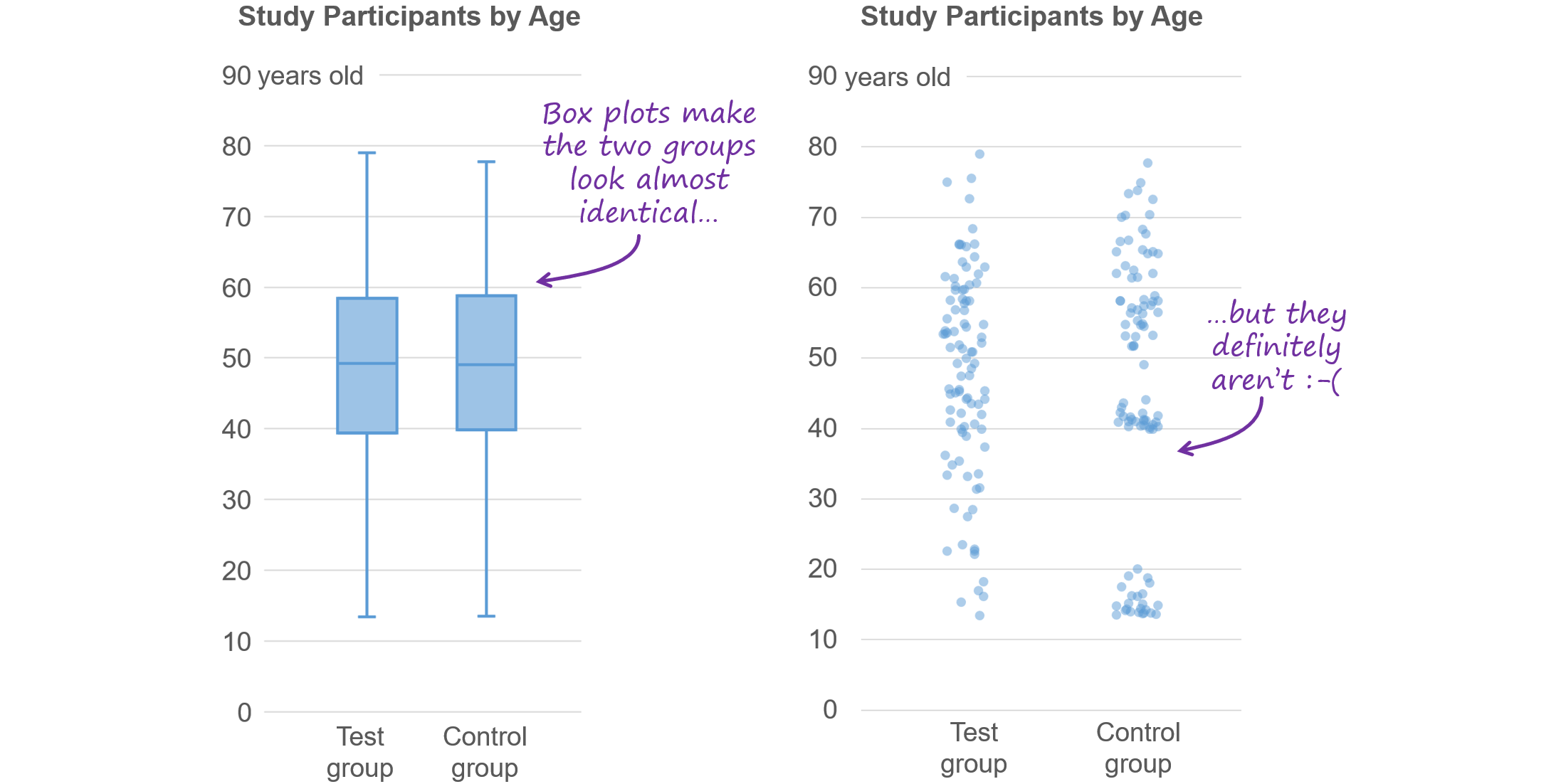

A number of people objected to this graphic from the 2021 article:

They objected that this wasn’t a valid use case for a box plot because box plots should only be used with unimodal (“bell-shaped”) distributions, not multimodal (“clumpy”) distributions, such as the “Control group” in the jittered strip plot above.

The problem with this objection is that it assumes that readers can always be certain that no chart creators will ever use box plots to show multimodal distributions. If you see a box plot in the wild, though, how can you be certain that the person who created it didn’t decide to use a box plot even though the data contained multimodal distributions? And what about box plots that are dynamically generated based on live data, and in which the distributions might be unimodal on some days and multimodal on others?

Basically, with box plots, readers are always left wondering if the distributions in the chart are unimodal or not—assuming that they’re even aware of this problem in the first place. Chart types like strip plots and distribution heatmaps, however, show unimodal and multimodal distributions clearly and so avoid this problem altogether.

“Box plots are a better choice for more data-savvy audiences.”

Even for audiences that are extremely statistically literate and very used to reading box plots, I’m not sure what benefit box plots would offer that wouldn’t also be offered by simpler chart types (sounding like a broken record now, I know). I am, however, pretty sure that box plots would hide potentially important information from them (gaps, clusters, etc.).

“We shouldn’t be afraid to use chart types that audiences aren’t familiar with. / We should try to teach audiences to read more advanced chart types.”

Totally agree. Indeed, in my Practical Charts course, I cover chart types that many audiences aren’t familiar with, such as step charts and scatterplots (see this article for a more complete list of “basic” chart types that many audiences aren’t familiar with). I cover these potentially unfamiliar chart types in my course because there are certain types of data and certain types of insights that can’t be communicated using simpler, more familiar chart types and so, sometimes, more complex or unfamiliar chart types are unavoidable, and you might need to teach the audience how to read them.

If you’re going to ask an audience to spend their valuable time and brain cells on learning a new chart type, though, there’d better be an “epiphany payoff,” as data storytelling expert Brent Dykes would call it, to justify that effort. I’ve just never seen any epiphany payoffs from box plots that couldn’t also be obtained with more familiar, less effortful chart types.

“There are no bad chart types. All chart types have situations in which they’re the best choice.”

I hear this all the time but I’m not sure why it would be true. It’s easy to forget that chart types are just human inventions, like printing presses and electric toothbrushes; they aren’t fundamental properties of the Universe, like mathematical principles. In fact, box plots are a relatively recent invention, having only been first proposed in the 1950s.

As with any other type of invention, there’s no rule that says that every type of chart needs to have situations in which it’s the best choice. Indeed, the pantheon of human inventions that were the best solution in exactly zero situations is well populated. I wrote more about this idea here.

—

Box plot defenders also virtually never mentioned one of the major problems that I described in the 2021 article, which is that box plots don’t make “visual sense.”

For example, have a look at the box plot below:

Even to people who are fairly experienced with box plots, it looks like there’s a large cluster of values in the central part of this range.

If you deeply understand box plots and think about it long and hard enough, however, you’ll realize that this box plot shape actually must mean that there are few values in the central part of this distribution, and this data set would have to look something like the jittered strip plot below (which is showing the same data as the box plot above):

That’s really, really not what the box plot seemed to be showing, though, and there are many other situations in which even experienced box plot readers must “think around” these perceptual paradoxes in order to avoid misreading the chart. Yes, this gets a bit easier with practice, but why use a chart type that forces readers to perform these kinds of cognitive gymnastics when there are readily available alternatives that don’t?

—

So, did any of these exchanges change my opinion about box plots?

As you can probably guess, I still don’t think that box plots are ever a better choice than alternative chart types, however, that’s now a much more thought-through opinion because people took the time to challenge it with such thought-provoking arguments, and I’m extremely grateful to everyone who chimed in. I remain open to being proven wrong and welcome additional comments and examples, just be sure to include a strip plot and distribution heatmap of the same data. To reply, comment on the post of this article on LinkedIn or Bluesky, or reach out to me via this contact form.

If you still feel that box plots have their place and you’ll continue to use them, that’s totally kosher. I certainly won’t call out anyone for using them, and all of this is just my opinion, of course. I would, however, still urge you to consider alternative chart types for one more reason that I haven’t mentioned yet…

Unfortunately, I’ve seen plenty of people feel needlessly stupid because they found it so difficult to read box plots, or failed to grasp them entirely. Unless you’re certain that all of your readers already understand box plots, avoiding making people feel dumb for no reason might be the best argument of all to consider alternative chart types instead.

As an independent educator and author, Nick Desbarats has taught data visualization and information dashboard design to thousands of professionals in over a dozen countries at organizations such as NASA, Bloomberg, The Central Bank of Tanzania, Visa, The United Nations, Yale University, Shopify, and the IRS, among many others. Nick is the first and only educator to be authorized by Stephen Few to teach his foundational data visualization and dashboard design courses, which he taught from 2014 until launching his own courses in 2019. His first book, Practical Charts, was published in 2023 and is an Amazon #1 Top New Release.

Information on Nick's upcoming training workshops and books can be found at https://www.practicalreporting.com/