Jump to the project: Gender Diamond / Gender Flower.

Watch and share the inspirational video: Can we queer gender data?

Technologies understand gender through their language, which is data. So how should algorithms read, quantify, and codify gender identities? How would we teach genderqueerness to AI? What data structure could accurately reflect the complex system of queer gender identities?

These big questions arise thanks to the theoretical framework provided by data feminism. Data feminism reminds us that data is not neutral — it carries the weight of societal biases and power structures. Society often makes decisions based on algorithms fed by biased data. Facebook is a useful example here: the social platform allows users to describe their gender identity freely, but its ads dashboard is still based on the old sex binary of ‘male’ and ‘female’.

Another theory, xenofeminism, studies the influence of technology on how we perceive and define our bodies in relation to societal, media, and governmental contexts. It suggests that both sex and gender are not naturally occurring, but are concepts constructed by humans and society. These concepts primarily categorize individuals through biological factors, such as gonads or chromosomes, but without considering the continuum of nature. This leads to regulations on biotechnologies, like birth control pills and testosterone shots, that further perpetuate the sex binary by only considering ‘females’ and ‘males’ as possible human agents.

As long as binary designations continue to be used and practiced, queer individuals will continue to be misrepresented. If our spreadsheets still continue to classify people strictly as ‘women’ and ‘men,’ or even more restrictively, as ‘female’ and ‘male,’ we overlook the spectrum of gender identities that exist beyond this binary. Plus, ‘nonbinary’ is not a single gender identity, but a broad term encompassing a variety of unique genderqueer identities.

Traditional methods of recording gender data fail spectacularly at capturing the depth and nuance of queer gender identities. For example, the simple three-category (female/male/other) system cannot detect crucial aspects of nonconforming gender identities, such as:

- the degree to which they align with conventional gender norms,

- the balance of their masculine or feminine characteristics, or

- how they choose to express or suppress their gender.

An additional problem of these traditional methods is that they take gender identities to assume heterosexuality and cisgenderness. Homosexuals (lesbians, gays) and plurisexuals (i.e. bisex and pansex people) live in profoundly different social groups that a binary ‘female/male’ dataset would never be able to grasp. A really inclusive gender survey, then, needs to record also the respondents’ sexual orientations as genders they are attracted to. Then, trans-/cisgenderness and trans-/cissexuality put an additional layer of complexity to the system. They emerge at the relation with the sex assigned at birth (ASAB) and, respectively, the current gender identity or sex. Essentially, since the 1990s, ideas from queer theory have been changing how we think about our bodies and sexuality: now we are primed to change our Excel spreadsheets, too.

Sexologists and information designers need to collaborate to create new gender data forms for the gender pluralist era. Indeed, we need new systems capable of capturing the rich, emerging complexity of gender and sexual identities.

In my master’s thesis project ‘QQQ Querying the Quantification of the Queer’ for the MA in Visual Communication Design at Aalto University in Finland, I investigated visualizations of the gender spectrum. These visualizations could be potential tools for gathering and structuring queer gender data. All the design research and testing was done collaboratively with gender-nonconforming and conforming people. Various experts in gender studies also shared their perspectives on the underlying ontology of the design objects and their possible uses. After all, feminist and queer universal design as well as queer universal design is not about designing for minorities, but with minorities.

Gender spectrum charts are increasingly visible

Of course, many gender spectrum visualizations already existed on the internet. They are often left unauthored, published in personal blogs or some queer subreddit. Indeed, people outside of the academic world have been trying to map out the complex landscapes of genderqueerness. These charts may lack scientific rigidity, often being mathematically incoherent and omitting details of their design process. Still, their authors were queer people, who are deeply implicated in the gender discourse and who might have the clearest insight on the subject matter.

Academic research in gender studies has provided intriguing methods of quantifying gender identities too. In the 1970s, American Psychologist Sandra Bem suggested that everyone has elements of both femininity and masculinity. To quantify these traits, Bem introduced the Gender Scales (1974) in which each individual scored from 0 to 6 following a process that tried to be scientifically objective. However, gender theories have evolved over time, and more recent models like the Genderbread Person (Killermann, 2012), the Gender Unicorn (TSER, 2015), and the Gender Identity Scale (2019) have emphasized that ideas of femininity and masculinity are subjective. Therefore, these models give individuals the freedom to assign their own scores based on how they personally identify with their own ideals of who is feminine and/or masculine.

My thesis tried to combine the best qualities of these graphic and mathematical representations of queerness in one design. The final charts merged the quantification and the discretization process of the Gender Scales with the self-attribution of the Genderbread Person and the Gender Unicorn. To respect the spectrum’s continuity, I enclosed the scheme in a usable interactive graphic form inspired by the Gender Vector (Hitch, 2021), which was the only chart I analyzed that used coherent mathematics.

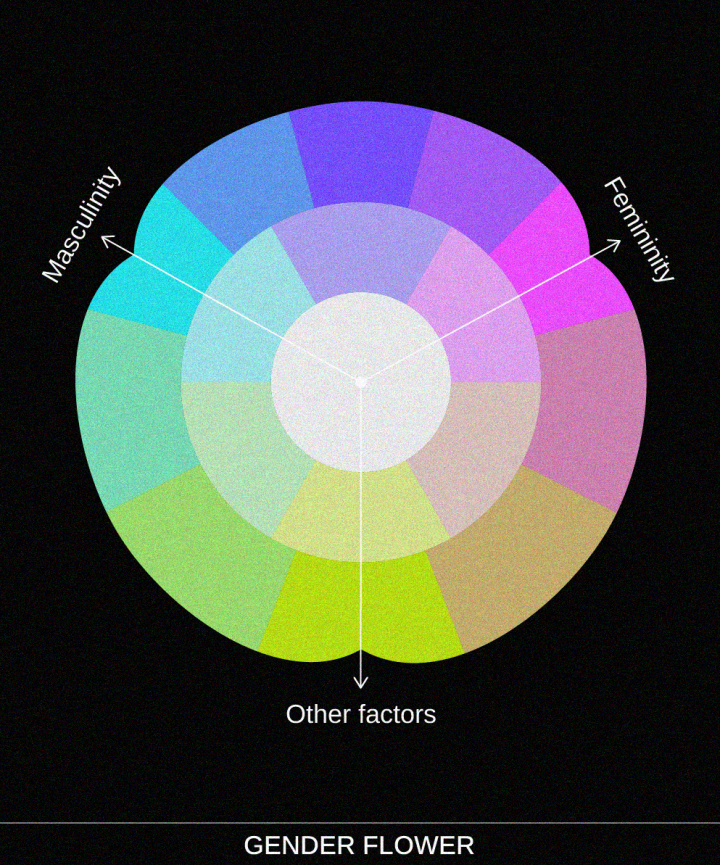

My selection process took inspiration from the Gender Square, which allowed genderfluid users to select multiple genders, thus representing a range of possible identities. I also included a third axis for ‘other factors’ in addition to the feminine and masculine ones, which I saw in some representations like the Gender Flat Tetrahedron, the Gender Cube (image above) and the Gender Unicorn. This addition aimed to accommodate those who adopt queer political stances who may not identify with traditionally gendered elements, therefore expanding the system of meanings within the gender spectrum.

Gender identity as an array of genders

In redesigning the gender data structure, I had to dig deep into what it means to be a queer data point. So what exactly are the requirements of accurately queering gender data?

Queerness, in queer theory, can be broadly thought of as an open attitude toward the future. On a personal level, being queer involves continuous reflection of one’s own sexuality: a queer person expects multiplicity, ambiguity, and change. Queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz claimed that queerness fundamentally rejects the present and insists on the potential for a different future — in other words, that queerness is a potentiality. This means that it might be impossible to define queerness as a static variable in the present since it is always pointing at what could be. Any data about queerness, then, must include the ability to change or see things differently in the future.

This point of view suggests that queerness has similarities with the mathematical concept of probability. My study used this idea to summarize and quantify queer gender identities as arrays of probable/possible gender outcomes in a nuanced way.

Let’s look at an example. Imagine an algorithm designed to understand a bigender person — someone with two distinct identities within their whole self. This person might identify as a masculine man 70% of the time, and as an androgynous woman for 30% of the time. These two gender identities are not mutually exclusive, but can be seen as potential outcomes, with the percentages representing their likelihood at any given moment.

Similarly, consider a person who identifies as pansexual. A system should be able to capture their attraction to all the different gender identities that exist on the spectrum. The system would show each potential partner, regardless of their gender, with different probabilities, reflecting the likelihood of the pansexual individual’s attraction to them.

This data could be tied to past experiences, current desires, or future inclinations, highlighting the fluid nature of gender and sexuality. The key point is that our understanding of gender shouldn’t be fixed or rigid, and data about gender and sexuality shouldn’t be either. It should be flexible and capable of reflecting changes over time.

Framing queerness as a probability of future possibilities enables us to use familiar mathematical and visualization principles in a data structure that stores gender. For example, we can limit labeling and binning in an effort to honor the vagueness that is intrinsic to queerness. We could also use uncertainty itself as a graphic translator for genderqueerness.

One way to address this is with Value-Suppressing Uncertainty Palettes, a type of tool described by Correll, Mortiz & Heer in 2018 that helps visualize not just value, but also the certainty of that value. For example, the closer someone’s gender identity is to agender-ness (i.e. the lack of a gender at all) the more uncertain is the prevalence of femininity or masculinity in their character. Using a palette like this can help reflect a position on a gender spectrum as well as the strength or certainty with which they hold that identity.

The dys-/utopia of the Gender Diamond and the Gender Flower

After much experimentation, I developed two digital products that I call the Gender Diamond and Gender Flower, both of which allude to the preciousness of the many shades of gender. In the QQQ website, I introduced the two interactive charts, allowing the users to explore the shades of the various gender combinations and letting them actively assess their gender identity and/or sexual orientation in a visual way.

Each segment of each diagram describes a specific combination of masculinity, femininity, and other factors and provides possible names for the identities that fall within that segment. The user can select multiple segments at once, or split their selection into primary identities and secondary ones to allow for users to self-identify with multiple identities and have the data structure accurately reflect that complexity (Galupo, Mitchell & Davis, 2015). The user tests confirmed that the two charts were able to describe mathematically many queer gender identities and gender-related sexual orientations. Try it yourself!

You may be wondering why there are two different charts — the diamond and the flower. I intentionally included two charts because I found that it helped educate the user on what the charts were trying to accomplish. During user tests with both gender-conforming and nonconforming individuals, starting with the three-axis chart with multiple selections overwhelmed most of the interviewees.

To solve this issue, the QQQ website uses a gradual approach to adding dimensions to the chart as a way to introduce complexity — first, the user sees a chart with two ‘familiar’ axes of femininity and masculinity. There is an ordered set of instructions that guides the user through each chart one step at a time, explaining related fundamentals of queer theory and my design choices that are intended to encompass each dimension of queerness. Only after the user has walked through the diamond chart completely do they discover the Gender Flower, which introduces a third axis. At any time, the user can hover over any part of the chart and see details in an inspection box which provides labels for each gender combination.

There is a problem, though. I prioritized reflecting queer complexity and ideals over simplicity or functionality, which means that it is challenging to learn how to read these diagrams. The long learning process for these charts suggests that they are too complex to be quickly understood by a first-time user without proper guidance or education. These designs do not aim to describe gender in a way that it could be applied to standard governmental forms. Instead, these diagrams envisioned a perfect world and spark discussion on the subject.

Still, some practical use cases can be easily imagined. With this new data structure, any phenomenon that is studied in relation to gender and sexuality can be mapped to a richly nuanced queer population, not just into the buckets of ‘men, women, and other.’ Furthermore, the Gender Flower and Diamond could be a precious resource in psychotherapy for gender-questioning people to allow people to explore options and more accurately self-reflect. For example, LGBTQ+ organizations such as Finnish Seta and Italian Zenatrans already use them to support gender-nonconforming people and to educate the population on queer issues.

Additionally, use of the Gender Flower and Diamond models could help the population better understand the fluidity and complexity of gender identities. Traditional gender labels, like ‘man,’ ‘woman,’ and ‘nonbinary,’ create distinct groups and frame queerness as something separate or other. These models treat extremely feminine women and extremely masculine men as simply two points among many on the gender spectrum. If these models were widely adopted, they could make these identities seem less alien and more accepted as part of the society. In other words, a systematic use of the Gender Diamond and Flower within society might create a queer utopia.

However, the line dividing utopia from dystopia is quite thin. If the two charts were used extensively, they could be used to enforce rules which control, surveillance, or power over specific segments of society would be enabled via data. For example, while very precise data on queer people’s identities might help the European Union develop policies that support LGBTQ+ people, at the same time, if the same data was owned by antigay regimes they could seek out and harm those same people.

Queer people are already mistreated and discriminated against — gathering information that defines and identifies them as a minority is a political action. As a general guideline, gender data should be gathered only when it is essential for the final goal of the collection (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022, S-6), and the user should always have the option to opt-out of providing gender-related information.

Gender is and always will be complex, and describing queerness in data will always be a balancing act. Whatever data structures we make to describe it — whether that be to oversimplify it into a binary, measuring it through multiple gender scales, or simply to ignoring it — will always carry a political choice with consequences for data integrity, technological innovation, scientific progress, and society.

It is important to keep researching and experimenting in this field, especially by investing in the collaboration between gender studies and information design. The Gender Diamond and Flower are artifacts born from this process, offering valuable starting points for further exploration. These models provide a more nuanced representation of the complex landscape of gender identities, challenging traditional binary conceptions.

Yet, they are not the end, but a step towards utopia. As our understanding of gender evolves, so too must our ways of representing it in data. It is our responsibility to strive towards more inclusive, flexible, and accurate representations, ensuring that technology truly reflects the diversity of human identities. The journey towards full inclusivity is an ongoing process, one that will continue to reshape our perception of gender and the ways we visualize it.

References

- Bem, S. L. (1974). The Measurement of Psychological Androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42(2).

- Canlı, E. (2017). Queerying Design: Material Re-Configurations of Body Politics [University of Porto]. Porto (Portugal).

- Correll, M., Moritz, D., & Heer, J. (2019). Value-Suppressing Uncertainty Palettes. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montréal (Canada).

- D’Ignazio, C., & Klein, L. F. (2020). Data Feminism. The MIT Press.

- Dunne, A., & Raby, F. (2001). Design Noir. The secret life of everyday objects. Birkhäuser Basel

- Hitch, B. (2020). www.dxdt.life. Retrieved 9th September 2023.

- Ho, F., & Mussap, A. J. (2019). The Gender Identity Scale. Adapting the Gender Unicorn to measure gender identity. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. doi.org/ http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000322.

- Killerman, S. (2017). The genderbread person v4.0. www.itspronouncedmetrosexual.com/2012/03/the-genderbread-person-v2-0

- Muñoz, J. E. (2009). Cruising Utopia. New York University Press.

- National Academies of Sciences, Egineering, and Medicine (2022). Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation (N. Bates, M. Chin, & T. Becker, Eds.). The National Academies Press. doi.org/10.17226/26424

- Preciado, P. B. (2013). Testo Junkie [Testo Yonqui] (B. Benderson, Trans.). Feminist Press. (2008)

- Trans Student Educational Resources (2015). The Gender Unicorn www.transstudent.org/gender

Fe Simeoni is an information designer. They are currently pursuing a PhD in computer science at the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, while collaborating with the Institute for Minority Rights and the Centre for Autonomy Experience at Eurac Research (Bozen-Bolzano, Italy).