We all know about being doomed to repeat the past, despite the fact that nearly all our current social, cultural, and political issues have precedence. On January 6th, a mob of Trump loyalists stormed the US Capitol building for several hours, violently acting on their politically opportunistic frustrations. The caustic emotions on display in Washington D.C. have set many people around the world on a journey to find answers.

For many of us involved in historic research, we naturally began to dig into our digital and physical archives to see what we might find to guide us. My focus is primarily on historical data visualization, and in specific, on pictorial statistics. In researching the work of Rudolf Modley, who had a massive influence on information graphics in the US from 1935 to the 1950s, I stumbled across a vast series of obscure pamphlets issued in the name of public education.

Let’s explore the history of this pamphlet series and the graphics sprinkled through nearly every issue, then dig into a single issue that remains relevant in light of the Jan 6th insurrection.

Knowledge for the masses: public affairs pamphlets

In 1936, as the US great depression was wrapping up, a non-profit group called the Public Affairs Committee was founded to increase public knowledge by publishing a series of inexpensive and fact-based pamphlets. Their constitution includes this extremely clear statement: “The purpose of the Committee is to make available in summary and inexpensive form the results of research on economic and social problems to aid in the understanding and development of American policy. The sole purpose of the Corporation is educational. It has no economic or social program of its own to promote, and it will at no time disseminate controversial or partisan propaganda or otherwise attempt to influence legislation.”

Pamphlets occupy an unusual corner of the American communications space, cheap to produce and easy to distribute to a wide swath of the American public. But the pamphlet carries a different communicative weight, not as authoritative as a book and usually written as a personal appeal. In The Political Pamphlet’s Origins and Purpose in the U.S.A., the authors argue “for much of its early history in America, the political pamphlet exists like a lighthouse on an island, crying “I am here, and I want to talk.”

Since its inception in 1936, the public affairs committee pamphlets nearly all contain pictorial statistics, most of them created by Rudolf Modley’s company, “Pictorial Statistics, Inc.” Modley was born in Vienna, started volunteering for Otto Neurath in high school, and eventually moved to the USA after law school to serve as a proxy for Neurath in America. After a series of fortuitous events, in 1935 Modley became the leading figure on pictorial statistics in the United States, bringing both a pedigree and an immigrant’s entrepreneurial hustle to the left-leaning field of “visual education”. Since Modley had early success with several New Deal agencies in creating charts to disseminate their message to Americans of mixed literacy, he became the darling of the widely influential magazine Survey Graphic. It was a natural fit to have his pictorial statistics illustrate the pamphlets in order to give them a more welcoming feeling while keeping their factual underpinning.

Maybe you can make out, in the small text above, that Pictorial Statistics, Inc, was a booming business with $30,000 a year revenue (about $500,000 in today’s currency). Rudolf Modley had a staff of about nine people creating pictorial statistics in numerous books — some of which he co-authored, such as 1937’s The United States: A Graphic History — as well as government and civic presentations, or the widely syndicated Telefact series that appeared daily in newspapers around the US.

In fact, the charts created for the Pubic Affairs Committee pamphlets became a key element in Modley’s content strategy. Charts were often made for the public affairs pamphlets, republished in Survey Graphic, then reused in newspapers, or redesigned into the more compact Telefact format for additional widespread syndication. There were plenty of opportunities for interesting, relevant, and important pictorial statistics and business was good.

Since more and more opportunities for pictorial statistics existed more competition was inevitable. In 1938, a few designers from Modley’s team, led by Henry Adams Grant, decided to strike out on their own and called their new company “Graphic Associates”. While this group is deeply obscure, and my research continues to learn more about their organization and scope, we know that Graphic Associates seems to take over (or inherit?) much of the work of Pictorial Statistics, Inc. during the early 1940s — including the ongoing series of public affairs pamphlets.

Graphic Associates brought a different flair than the more austere work of Modley (and Neurath before him). You can sense an evolution of the format in the way Graphic Associates hand draws their work, adding a more humorous and cartoony edge while retaining the pictorial statistical rigor. The designs become more graphically dynamic with an illustrational flair in keeping with the times. As seen in the charts above, the team begins to blend different approaches of visual comparison, flow chart, and even comic storytelling into their work.

In the scope of this article, the detour into the work of Modley and Graphic Associates serves to connect us to the common goal of these pamphlets — to increase public knowledge. While my research on pictorial statistics continues to unearth lost masterworks of information design, the message of these small but powerful pamphlets still proves relevant to today’s world.

One of them is so interesting, in light of the January 6th insurrection, that I’d like to discuss it in particular:

Exploring a few key passages from “War and Human Nature”

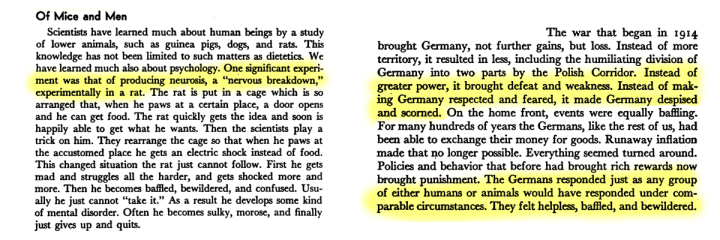

Considering the relatively short gap between the World Wars, there was naturally a lot of concern about the long-term emotional states of the defeated people of Germany and Japan. Much of the world was still rebuilding, and this pamphlet considers the root causes of the frustrations that began in confusion, transformed into fascism, and resulted in destruction. Sound familiar?

By examining the underpinnings of unrest and violence, its writer, Sylvanus Duvall, makes a clear and empathetic case to consider the unfulfilled needs that result in delusion, conspiracy, manipulation, and insurrection. He elaborates on how to confront these confused beliefs while staying true to a shared cultural identity and even comments at length on the democratic conditions (the ballot and the courtroom) that must be met to ensure a fair and equitable resolution of disputes.

While the terms of this book — “war,” “peace,” “Nazis,” “dictatorship” — may feel out of place when considering American politics in the time of Trump [well, maybe not], the human insights feel precisely the same. The confusion and frustration and blame can easily be witnessed across our social media newsfeeds; the historical precedent clearly visible over and over again in this essay written 75 years ago.

The passages below highlight some of the main themes in War and Human Nature and I’ll add some editorial interpretations on each.

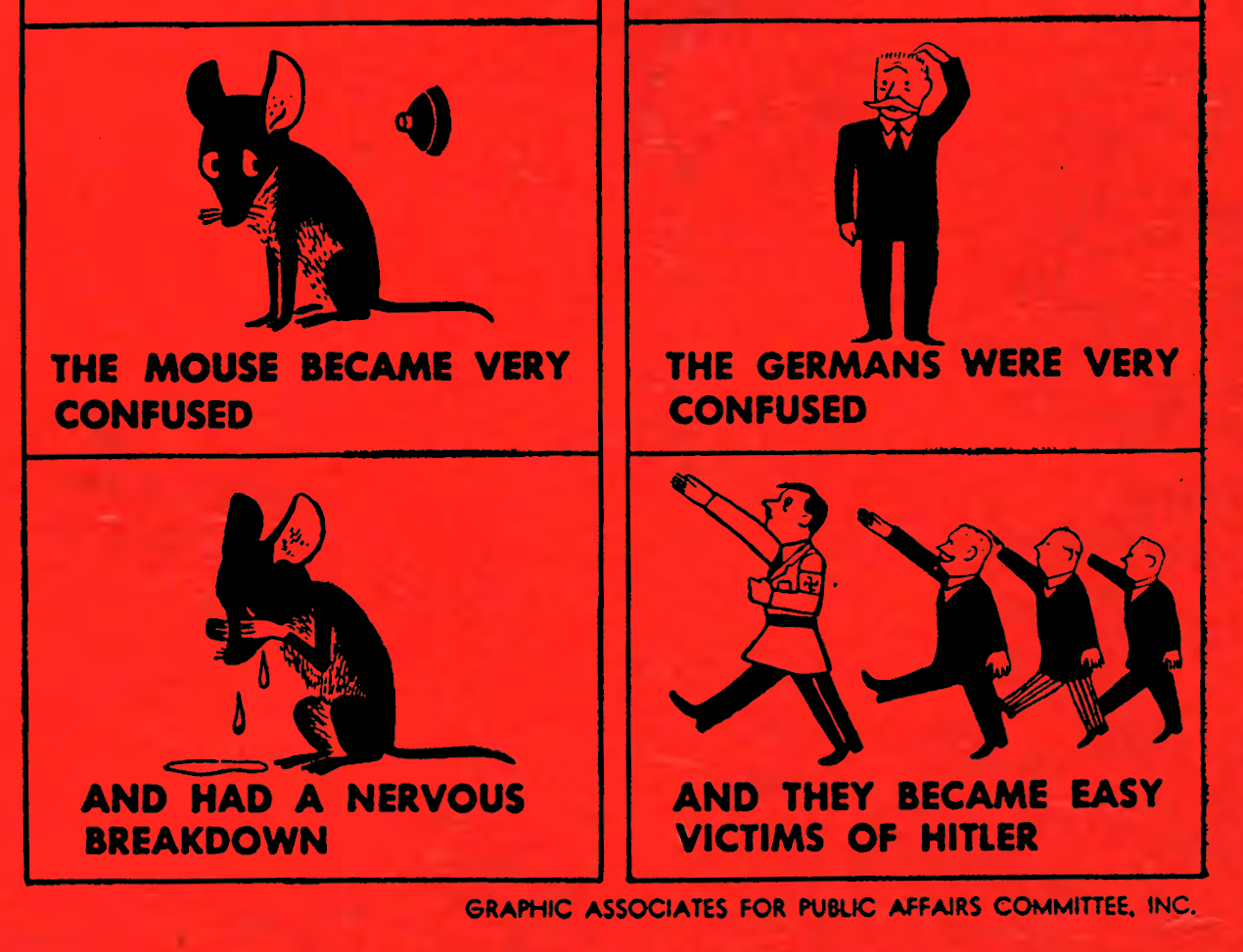

Probably the strongest argument in the pamphlet is this relationship between confusion and susceptibility to influence. While the focus is on the defeat of the Germans in WWI which left their culture and politics vulnerable to the influence of Adolph Hitler, the author strikes a haunting connection to that of the mouse with a nervous breakdown. The Graphics Associates team was all too happy to elaborate visually in this incredible illustration:

Certainly, the influence of the media (left and right) along with gamified conspiracy culture helped to give the insurrectionists an altogether surreal cosplay appearance, or as the headline in MotherJones read “Trump’s Trolls Turned Their Violent Fantasies Into Reality”. The weaponization of the foundational confusion here is obvious. Beneath the hyperbole, rhetoric, and fanaticism, many people in the Trump camp are scared and confused. As a group, they would be almost pitiful if it weren’t for their grotesque embrace of racism and intolerance.

The belief that the MAGA faith has in a previous time where America was “Great”, speaks to the need to try to re-build a worldview that they can understand. Yet a challenge to the phrase “Make America Great Again” was always the question “…for who”? This insecurity in a current world where a Black man can be US President and urban populations determine fair elections just does not compute for this adrift group of people who feel abandoned by their political leaders — except for Trump.

Certainly, a global pandemic that emphasizes income disparities and prevents face-to-face connection only makes it all worse. The missing tether to a community, workplace, or family allows those under the influence to fall further down the rabbit hole.

The frustration is so clearly evident in the videos from the insurrection. The toxic blame game that was weaponized by Trump beginning in “build the wall” and ending with “kill Mike Pence” certainly can be seen with historic precedent. Anyone that Trump blames has been an easy target for his supporters to defect their rage. Again, the Graphic Associates team elaborates with a graphic to support this argument:

Frustration, blame, education, understanding, and tolerance

We can see the anger and urgency of the insurrectionists, but in order to take steps towards actually healing our country, we must address the nature of this collective frustration. Certainly, the bigotry and toxic masculinity bundled with algorithm-boosted social media call-to-arms flooding corners of American helped to plant the violent seed.

In order to resolve these frustrations, we must acknowledge the reasons why such confusion was allowed to fester and take hold. We must account for ever-growing income disparities. We must acknowledge the lack of accountability by our public and political figures, the inconsistent policing and enforcement of all human rights, and the unattainable goals portrayed in our media.

This all feels like way too much to figure out — but history shows us it has been considered and acted on before. If the populations of Germany and Japan could both rebound and become global powerhouses in the decades after WWII, why can’t we see reconciliation between neighbors and families with more in common over a shorter period of time? It’s going to take a lot of hard work, but a better, more equitable future is ahead if we focus on the underlying causes of this dark moment of American history and work together to overcome it.

Here’s the whole pamphlet “War and Human Nature”, 1946 as PDF

Jason Forrest is a data visualization designer and writer living in New York City. He is the director of the Data Visualization Lab for McKinsey and Company. In addition to being on the board of directors of the Data Visualization Society, he is also the editor-in-chief of Nightingale: The Journal of the Data Visualization Society. He writes about the intersection of culture and information design and is currently working on a book about pictorial statistics.