Some days it feels like my first words were, “I hate math.” There’s a stereotype that creative ‘right-brainers’ can’t do math, and as a writer and an art student, it was the one stereotype I was happy to fit. I wonder now if it was simply easier to say “I hate” rather than “I don’t understand.”

Now that I am older I am starting to realize my stereotypes of math were wrong. I always thought that, because I didn’t understand it, I would never be able to do it. I am predominantly a creative right-brainer, so it was easier to accept that and spend my time on other subjects (ones I enjoyed more). But that kind of thinking is misguided.

We like to categorize people as either right-brained (those who are creative and artistic) or left-brained (those who are logical and analytical). It’s a common belief that if a person is dominantly one, then they can’t be the other. This is simply not true. Math is a complex, multifaceted subject that requires a wide variety of skills. In its most basic format, we need to be able to understand the problem and the way to solve it and that has to be expressed through language, whether verbally or written.

But math is more than that.

Take data analysts—they take a set of data and have to ask the right questions so that they can apply data correctly. Then they translate it, making it easy for people and businesses to understand what it means and why it matters and, chances are, they will achieve this with storytelling. Research conducted by Duke University and the University of Michigan has shown that communication between the left and right hemispheres increases when we work on math problems. While it’s true that left-brainers might have an upper hand, this is largely due to the fact that traditional teaching, such as lectures where the students are expected to take notes, are more geared towards left-brained thinking.

Educators have started to realize that there is a problem with the way we teach math and are trying to come up with solutions. One train of thought is that kids don’t believe they will use it after school, so logically the solution would be applying it to their careers and showing them just how useful it is. However, kids aren’t interested in abstract somedays, they want to be engaged now. The key is to make math fun and engaging; to show the wonder and beauty of it. As role models to children, it’s our responsibility to do just that.

1. Showcase the wonder

There is beauty to math. It’s more than just numbers and formulas—geometry is present in nature and formulas can be found in almost everything we do. The American Mathematical Society created a list of galleries showing beautiful mathematical images. There is also beauty in the way numbers line up and in their patterns, particularly if you think of the Fibonacci sequence. Fundamentally, math is a means of exhibiting and satisfying curiosity. It’s about asking questions and finding explanations, much like data visualization. There is a wonderment to it, but somewhere along the way we lose that magic. What if we started teaching it like an art form? Instead of looking at it in black and white—we teach it in colors.

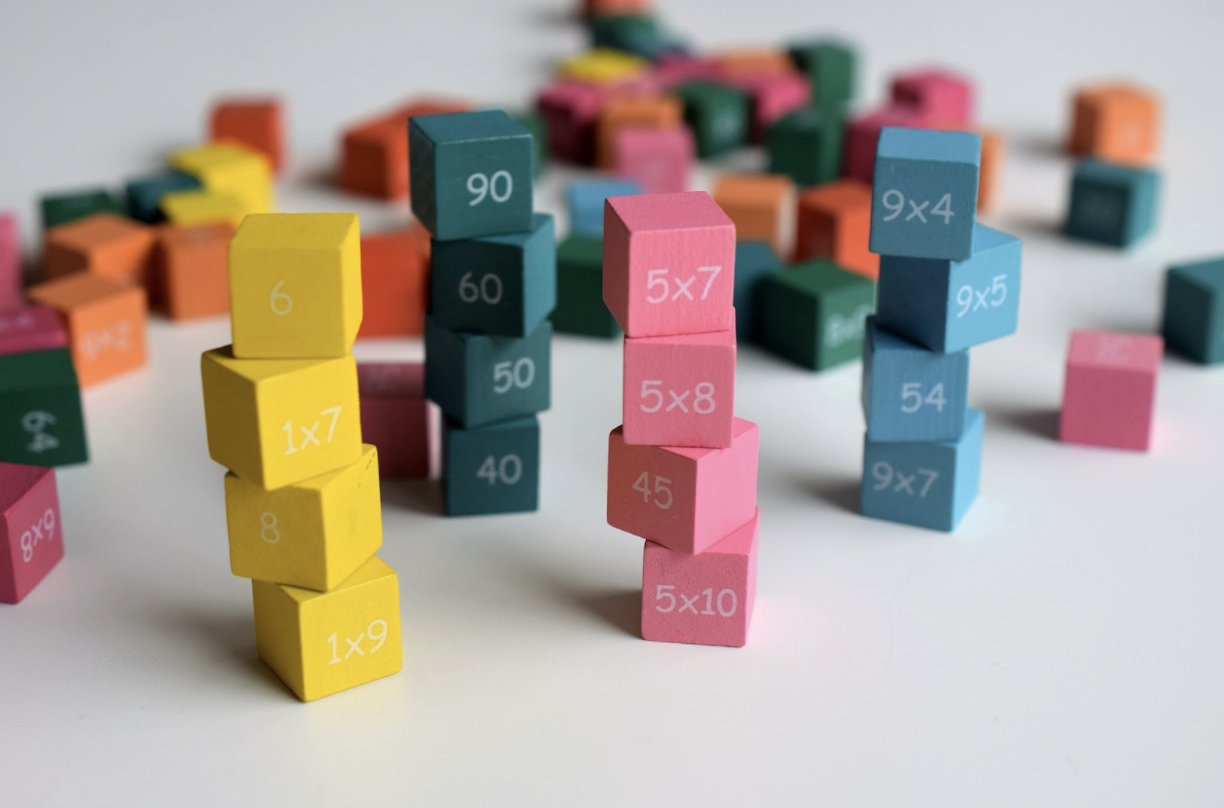

And by colors, I mean using colors to separate different processes and numbers. Have the kids draw what they are learning so that they can better visualize and understand what it is they are doing. Bring in music by creating songs about numbers or formulas. It’s already commonplace to use physical objects such as manipulatives so that math becomes something physical for children to touch. By expanding on these creative ideas, students will likely be more engaged in their classrooms.

2. Invoke the power of storytelling

A large part of the problem is that school often focuses on memorization. Teachers give their students their information, they memorize it for their test, and then it’s gone. Forgotten. Some facts will stick, but most will disappear. Education should be focused on building skills that children will need as adults, such as problem-solving and analyzing. But sometimes memorization is necessary. When it is needed, teachers should consider approaching it through storytelling. Stories are powerful—largely because the good ones leave an impact. They’re memorable because they allow us to connect to ideas in more meaningful ways. Try giving each number and fact a story, write it on a flashcard and see its effect for yourself. By using the emotion and power of narratives, students will better be able to form mental pictures in their minds and retain the intended lesson.

3. Incorporate math into daily life

Kids are heavily impacted by those around them. If they hear negative opinions about math, they are likely to start thinking about it in the same way. If you are a role model to a child, show yourself being confident with it whenever you encounter math. More than that you should encourage them to use math in their daily lives.

When you are at the store, you can ask them to figure out how much some items cost or how long it will take to save up for a goal. Make math relevant. Figure out what children are interested in and find a way to tie math into it. Play math-based games such as chess, checkers, dominoes, or Yahtzee.

4. Avoid reinforcing stereotypes–even inadvertently

Stereotype threat is a serious concern. It’s when we underestimate a group’s ability to do something that they actually begin to underperform. This is especially true for girls. There is a nasty stereotype that girls can’t comprehend math as well as boys. Perhaps this is why only 26 percent of all computer and mathematical positions are filled by women, according to a study published in the Science of Learning.

This stereotype has been proven to be untrue by several studies—one of which was done by Jessica Cantlon at the Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. She studied MRIs of groups of boys and girls as they watched educational videos and found there to be no biological difference. The difference comes from unconscious messages spread through society. Teachers spend more time with their male students and the girls begin to pick up these cues that math just isn’t for them. Educators, and people influencing children, need to be aware of these stereotypes and make sure that they are giving all children equal access to the same education.

5. Broaden your perception of literacy

Parents tend to put more emphasis on their children learning how to speak, read, and write, while neglecting math. It’s understandable because children have to learn to talk before anything else, with reading and writing following close behind. These skills are essential to communication and are needed before attempting any other type of education. Still, math is just as necessary. It surprised me how much math is foundational to a field like design—ranging from understanding geometry and grids to knowing portions and scales.

Introducing math early will give young learners a better foundation, helping them down the line. But make math fun and engaging—let it keep its wonderment and magic. I can’t help but wonder if someone had approached teaching math differently when I was younger if I would feel differently towards it. I still don’t enjoy math—and I doubt I ever will—but I now have a healthy appreciation for it and I know just how important it is for young children to feel the same. They need to know that you can be good at both language arts and math—that it doesn’t have to be either-or.

It’s easy to get wrapped up in labels: of being a creative or a scientist, left brained or right. We don’t have to limit our identity to one thing. Data analysis, a conventionally STEM career, requires creativity in the way they break down data and reorganize it into meaningful and compelling narratives. We should inspire children to do the same, allowing them to be creative without limitation.

Christen Spehr is a student at Savannah College of Art and Design, completing her BFA in Writing. She is passionate about storytelling and wants to write children’s literature and adult fantasy.