Italian designer, Bruno Munari, famously argued that “Art shall not be separated from life: things that are good to look at, and bad to be used, should not exist.” Beauty arises when form is aligned with its exact function and material constraints—form follows function. I have recently been thinking about this conviction through the lens of two specific interests of mine: data visualisation and urban greening. One is rooted in digital representation and the other in physical space, yet both fields share a foundational principle of design. Both disciplines strive to organise complex information and environments in ways that are legible, functional, and at their best, to the benefit of human experience. A well-designed visualisation engages its audience through aesthetic appeal, drawing them in and making them more inclined to explore the information. Likewise, green spaces that are beautiful, not merely decorated, but beautiful in their functionality and integration with nature, are more likely to be used and cared for. They build civic pride and contribute to overall wellbeing.

I lived in London for a decade, the final three and a half years spent in Brixton. There, I would frequent two distinct green spaces. Brockwell Park, a large public park where the neighbourhoods of Brixton and Herne Hill meet; and Brixton Orchard, a small community garden situated directly opposite Lambeth Town Hall. It was during this period that I developed a keen interest in community-focused urban green spaces. In the winter of 2023, I left London for the densely populated city of Taipei, the Taiwanese capital. I moved into an apartment within walking distance of Da’an Park, the city’s central green expanse, but the true joy was the city itself: greenery along every street and tucked into every corner with plants of every species tumbling down off balconies. From my kitchen window, I could see the man who lived in the top floor apartment opposite had cultivated a veritable jungle atop his roof, in which he would emerge daily at sunset to water his plants and sit quietly on a bench he had nestled under his palms. This set-up is quite common in Taipei. As Clarissa Wei described the city for The New York Times, it is “a literal urban jungle—ferns and large elephant ear plants sprout through the crevices of roofs and sidewalks with wild abandon”. Across the street from my apartment, a pocket-sized neighbourhood park was a constant theatre of intergenerational life, teeming with both children and the over-seventies. I was surrounded by nature in the heart of a capital city, and I loved it.

Urban greening, or green infrastructure, is the deliberate integration of vegetation—street trees, parks, green roofs, and living walls—with urban development to provide ecological, environmental, and cultural benefits. The protection of nature in urban spaces is essential for sustaining natural ecological cycles, and provides crucial cultural ecosystem services: it softens the harshness of urban infrastructure, ensures a critical connection to nature, improves general wellbeing, and fosters social interaction. Taipei relies heavily on green spaces of all types for public life. The city serves as a compelling case study for urban greening in compact cities, defined by its “top-down” planning approach born of its limited land area. A study by Peilei Fan, professor of urban and regional planning, and colleagues, found most neighbourhood centres and one subcenter in the city “exhibit both high compactness and good green accessibility”. The central city rests on the ancient Taipei basin, bounded by major rivers (like the Tamsui) with steep, mountainous terrain rising abruptly on most sides of the basin. Other examples of compact cities in East Asia include Hong Kong and Singapore. London, by contrast, is a city that grew organically over centuries, resulting in its pattern of “urban villages”.

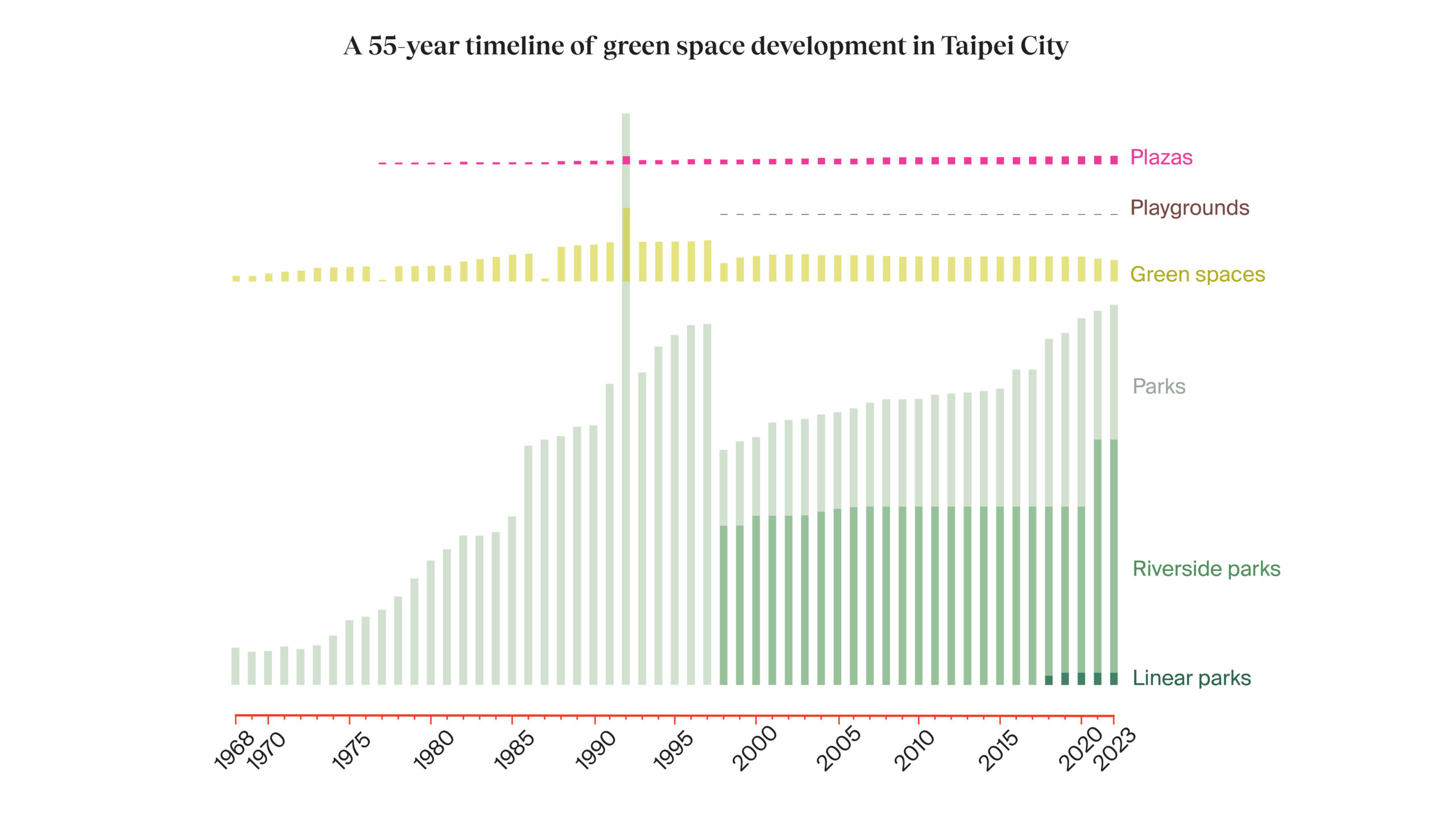

Since 2010, Taipei’s urban planning policy has shifted its focus from a broad, visible green strategy toward practical green landscaping schemes. This strategy gained momentum around 2014 with the emergence of an urban regeneration programme and the prioritisation of the development of small green spaces, such as river corridor greens and pocket parks. Through government funding and the lease of state land, the Taipei Beautiful Programme and the Open Green Project have delivered the development of small green spaces across the city. A complementary effort, the Garden City initiative further promoted urban agriculture, including citizen farms (allotments), community plots, and rooftop gardens, particularly on school buildings. I used open source data from the Taipei Government Open Data archive to illustrate the development of green spaces in Taipei City over the last fifty years. I first translated the raw data from Mandarin, followed by exploratory analysis using Python. I plotted the time-series data as a raster-style graphic, aiming for an aesthetic that evokes an interconnected urban ecosystem. I was interested in mapping the locations of developed green spaces, and I relied on data from the Taipei City Water Green Space Atlas. I manually classified all the green spaces listed in the atlas according to the definitions of the Garden City initiative.

Effective data visualisations and well-planned urban spaces seamlessly blend aesthetics and utility, aimed at enriching public experience and understanding. In data visualisation, this means selecting graphs, layouts, and interactive elements that communicate the underlying data with clarity to engage the target audience. Similarly, in urban greening, this translates to designing spaces and infrastructure that provide ecological benefit and prioritise the needs of the local community. Form follows function. Munari viewed the designer as a mediator, bridging the gap between expert knowledge and public life: “The designer of today re-establishes the long-lost contact between art and the public, between living people and art as a living thing.” Without effective design in data visualisation, the data remains inaccessible. With it, visualisation can empower the public to understand, question, and engage with critical issues. Urban greening, by its very nature, is public-facing. The design of urban green spaces is about making a city a usable and sustaining environment.

Of course, data visualisation can also act as a bridge between academic research, expert knowledge, and public understanding within urban greening contexts. As someone whose academic background is in Neuroscience, and not Urban Greening, I write this from the perspective of the public that these policies need to engage; the public must be integral to the decision-making process for the planning and design of their local green spaces. The ‘Citizen Dialog Kit’, an open-source toolkit, was developed to leverage situated visualisation within public spaces through a set of interactive, wirelessly networked displays. By making local environmental data visible and understandable, it invites discussion and feedback from diverse community members who might not typically participate in traditional planning meetings. Residents can see the tangible results of past efforts and then contribute to ongoing dialogues about future greening priorities. In a recent study, socio-environmental scientist Thomas Mattijssen and colleagues presented a participatory application of GIS that bridges the gap between data-driven and citizen-centred urban greening. The authors used spatial modelling in community workshops where residents contributed local knowledge to enable researchers and local citizens to jointly identify greening criteria, translate them into indicators, and pinpoint potential greening locations. This accessibility fosters democratic participation in environmental decision-making.

Visualisations serve as a powerful tool to engage community members and translate complex datasets into compelling narratives, increasing both understanding and acceptance of environmental initiatives. For example, RisingEMOTIONS, a data physicalisation and public art installation situated outside the East Boston Public Library in 2020, aimed to engage communities directly affected by sea-level rise, encouraging their participation in planning adaptation strategies. Looking ahead, emerging technologies offer significant opportunities to enhance the role of data visualisation in urban greening, and more broadly, climate policies. Innovations such as AI-assisted personalisation, mobile technologies for context-aware experiences, and real-time environmental sensing can amplify its impact, creating tools—imagine an app that allows a Taipei resident to visualise the projected, real-time impact of a new pocket part on local air quality—that make planning tangible. For a comprehensive look at how data visualisation can be leveraged to address sustainability goals, a recent article by social computing professor Narges Mahyar provides an excellent review.

In adhering to Munari’s principles, where design prioritises functionality, clarity, and intrinsic beauty, the design of data visualisations and urban green spaces finds its highest purpose in its utility to the public: “Art shall not be separated from life.” At their best, both disciplines demonstrate that “beauty arises from functionality”—whether in the efficient form of a bar chart communicating a climate trend or the purposeful design of a pocket park managing water runoff—both are functional in their communion with the public. Moreover, data visualisation can become an indispensable tool for urban greening. By effectively communicating complex planning concepts and policies, visualisation fosters community involvement and informs policy decisions that directly benefit local communities.

All images designed and provided by the author.