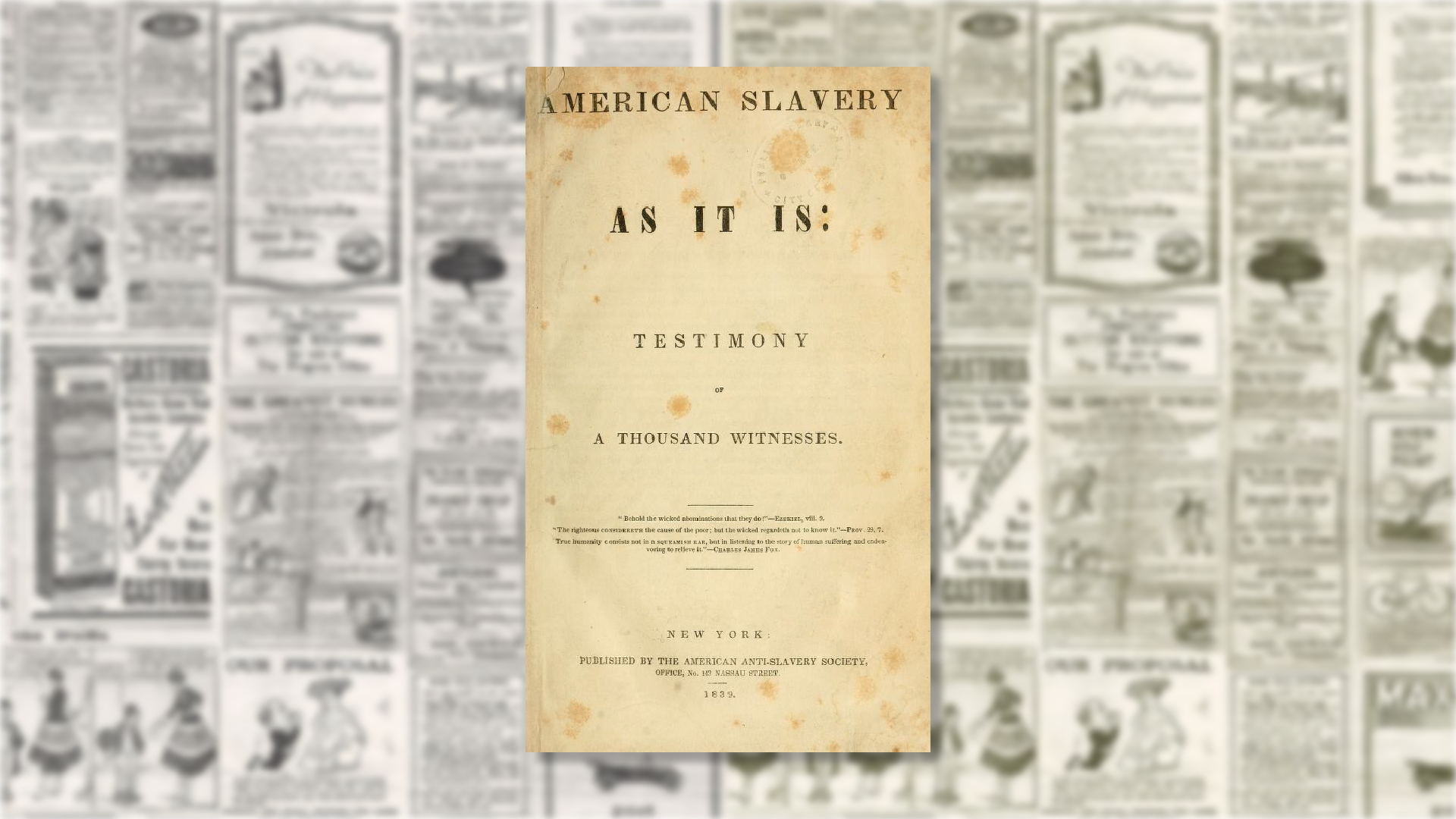

In the mid-19th century, Angelina and Sarah Grimké, alongside Theodore Weld, embarked on a novel data-driven project to aid the fight of the U.S. abolition movement against slavery. By meticulously collecting and analyzing thousands of advertisements and articles from Southern newspapers, they created a comprehensive database that revealed the harsh realities of slavery. An innovative approach transformed this existing information into powerful evidence against the institution of slavery. The project demonstrates the potential of data to not only inform but also to drive social change, highlighting the importance of how data is collected, interpreted, and presented. As such, the work stands as a foundational case study in the effective use of data for advocacy and storytelling, emphasizing the power of data to shape public opinion and effect change.

Drawing from the abolitionists’ database project, we identify five key lessons about data collection, analysis, and advocacy. These insights are crucial for understanding the transformative power of data in historical and contemporary contexts.

Pillar 1: Consider context

The authors fundamentally changed the function of the newspaper clippings they collected by recontextualizing them. Ads for runaway slaves and other related materials, initially meant to serve the interests of slaveholders, were repurposed to highlight the cruelty and brutality of slavery. By aggregating these ads and analyzing them as data, the authors shifted their function from mundane, commercial notices to powerful indictments of the slave system. This recontextualization transformed the clippings into compelling evidence against slavery.

The original context of the newspaper clippings, meant to serve the slave economy, was altered to expose the inhumanity of slavery. This shift in context, from a Southern, pro-slavery perspective to an abolitionist context, allowed for a new interpretation of the data. The authors used this recontextualization to challenge prevailing narratives about slavery and to provide a stark, factual representation of its brutality.

The text demonstrates how data and information can be transformed and repurposed through context and interpretation, changing their meaning and impact significantly.

Guidelines:

∆ What are the benefits and limitations of the dataset for the intended uses? Under what contextual conditions do the benefits cease to exist?

∆ Validity: What are the specific timeframes, durations, and conditions under which the dataset remains valid and accurate?

∆ What constraints are there on the intended uses of the dataset due to the methods employed in its data collection?

Pillar 2: Beyond numbers – the power of qualitative data

Testimony in the abolitionists’ project was crucial, as it comprised personal accounts from those who lived in or were familiar with the South, including former slaveholders. This personal testimony provided a compelling narrative about the realities of slavery.

The role of investigation, particularly through the use of newspaper clippings, was equally significant. The authors meticulously combed through thousands of newspapers, extracting and categorizing information. This process transformed the newspaper clippings into a database-like resource, which provided a factual, evidence-based counterpoint to the personal testimonies.

This combination of personal stories and systematically gathered data presented a powerful and comprehensive view of slavery.

Guidelines:

∆ How does qualitative data complement quantitative findings in broadening the understanding of a complex topic?

∆ In what ways can qualitative data reveal aspects of a phenomenon that quantitative data alone cannot capture?

∆ What are the challenges and considerations involved in collecting and interpreting qualitative data?

Pillar 3: (Not) strangers in the dataset

The Grimké sisters and Theodore Weld were deeply embedded in the context and content of their dataset. Their intimate knowledge of the subject, personal experiences, and innovative methods of collecting, interpreting, and presenting data distinguished their work from being that of mere outsiders or strangers to the dataset. They exemplified a profound connection with and understanding of the data they worked with, which was crucial in their efforts to combat slavery.

Sarah and Angelina Grimké, originating from a family in South Carolina that owned slaves, chose to renounce their heritage and dedicate themselves to the abolitionist cause. Their upbringing in a Southern slaveholding family provided them with the ability to recognize individuals participating in the slave trade and uncover the implications of practices alluded to in the newspaper ads of slave owners.This distinct background empowered them to effectively repurpose these advertisements as potent instruments in their fight against slavery.

Guidelines:

∆ How can collaboration between individuals with diverse backgrounds and skills improve the processes of data collection, analysis, and interpretation?

∆ How is the effectiveness of data collection and presentation strengthened when a data project includes individuals who possess personal experience or an in-depth understanding of the subject matter?

Pillar 4: Data is (about) people

Giorgia Lupi emphasizes the personal, human aspect behind data. The abolitionists’ project reflects this principle by turning numbers and statistics about slavery into personal stories and experiences. Through qualitative data like personal testimonies and narratives, they presented experiences and realities of enslaved people, making the data more meaningful and impactful. This approach aligns with Lupi’s idea of connecting numbers to real-life experiences, emphasizing that behind every data point is a human story. Putting people at the center of data helps us understand and foster empathy about a given topic.

Guidelines:

∆ How can data collection and analysis methods be designed to capture and reflect the individual stories, emotions, and experiences behind each data point, ensuring a more human and empathetic approach to data interpretation?

Pillar 5: Ethical considerations in data usage

The abolitionists’ database project addressed ethical considerations by carefully editing the advertisements they used to remove most identifying information about the ex-slaves. This deliberate action ensured that the converted ads did not inadvertently serve their original purpose of providing information that could lead to the recapture of these individuals. By focusing on the broader issues, such as the separation of families, rather than individual characteristics like an escapee’s “rather sulky appearance”, Angelina Grimké, Theodore Weld and Sarah Grimké were able to use the data to support their antislavery arguments without putting the subjects of the data at greater risk. This approach highlights a thoughtful balance between using data for advocacy and protecting the individuals represented in that data. It underlines a critical aspect of working with sensitive data: the need to balance the informative and advocative goals with the potential risks and impacts on the subjects being represented.

Guidelines:

∆ Consent and privacy: Have I obtained informed consent for all the data I am using?

∆ Bias and fairness: Does my data collection and analysis process minimize biases, and am I ensuring fairness in how the data is used and interpreted?

∆ Impact: What are the potential impacts of my data project on individuals and communities?

∆ Accessibility: are my data visualizations excluding people?

The pillars above provide invaluable guidance for those engaged in data-related efforts. They underscore the importance of context, embracing qualitative data, adopting a human-centered approach to data, fostering collaboration across diverse teams, and prioritizing ethical considerations when creating responsible and impactful data-driven products.

The abolitionists’ project stands as a testament to the immense power of data as a tool for societal change. This example serves as an inspiration for contemporary data-driven initiatives. It illustrates the importance of a deep connection with the subject matter, the value of diverse perspectives in data analysis, and the power of data in storytelling and advocacy. As we continue to advance in the field of data science, the lessons from this project remind us of the ethical responsibilities that come with handling data and the potential it holds to effect positive change in the world.

References:

Gruber Garvey, E. (2013) ‘ “facts and FACTS”: Abolitionists’ Database Innovations’ in Gitelman, L. (ed). ‘Raw Data’ Is an Oxymoron. The Mit Press.

Klein, L.F. and D’Ignazio, C. (2020). Data feminism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mit Press.

Lupi, G. (2017). Data Humanism – A Visual Manifesto. Available at: https://giorgialupi.com/data-humanism-my-manifes to-for-a-new-data-wold (Accessed 2 Apr. 2024).

I am an experienced software engineer with over 10 years of experience – currently working as a software engineer at Thomson Reuters Labs, collaborating to accelerate combining editorial and content creation with AI/ML capabilities by creating tools that allow journalists to efficiently produce high-quality content. My academic path has led me from earning a Bachelor’s Degree in Computer Science at Vassar College to currently pursuing a Master of Arts in Communicating Complexity at the University of the Arts London, where I am studying making complex information accessible and engaging. What interests me most is visual communication and using this form of communication to disseminate technical, scientific, social, and environmental content.