The practice of data storytelling often focuses on weaving a narrative by highlighting themes from a dataset. Author Dan Bouk flips this conventional practice on its head by instead telling a powerful story about the data itself. He challenges the objective status we frequently assign to data and pulls back the curtain on how one of the world’s most important datasets came into being – the United States decennial census.

His book, Democracy’s Data, walks readers through the processes by which census data was conceptualized, gathered, and operationalized within the context of the historic 1940 census. The insights that emerge from this compelling narrative provide in-depth insights not only into the specifics of the US census, but also speak to the care and attention we should take when working with all datasets, especially those that aggregate individual human stories. In his book, Bouk writes,

“[O]ne cannot fully understand any data unless one knows what it includes, what it privileges, what is deprecates, and what it overlooks.”

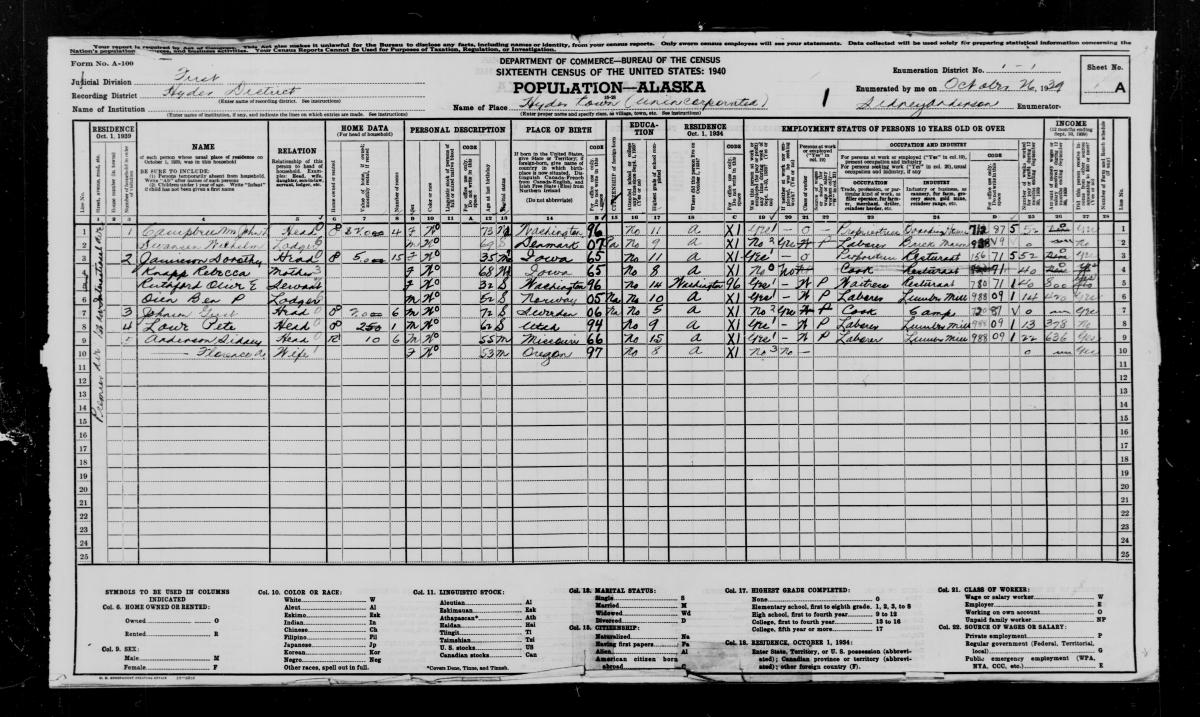

In 2012, the full data for the 1940 census was made publicly available, following the tradition of census data being fully released 72 years after its completion. Dan Bouk leverages this historical dataset to highlight the processes by which the Census questions were selected, the interactions between enumerators and residents where the data was gathered, and finally how the data was then used by the government for the furtherance of democracy and also for more questionable war-time objectives.

In 1939, a large group of mostly white men, representing various federal government departments, labor unions, business representatives, and others, gathered in DC to decide what questions would be asked of all Americans in the census. This highly politicized process was consequential in determining not only the finalized census data, but also in shaping the political landscape of the country. In previous years, immigration status was included on the questionnaire and the results were used to fuel strong nationalist sentiment and fear, which eventually led to the restrictive Immigration Act of 1924. In addition to the types of questions that were asked, it was also significant to determine what the list of acceptable answers would be for these questions. Bouk devotes a chapter to exploring this issue–focusing in particular on the challenge of categorizing non-traditional family structures and the frequent umbrella term “partner” that was used to describe many on the margins of society.

A large number of enumerators were recruited and trained across the country to undertake the ambitious task of counting every single American and to record their answers to the census questionnaire. The interactions that occurred between these enumerators and local residents profoundly affected the quality of data that was then aggregated. Seemingly simple questions, such as recording the resident’s name, required negotiations to align an individual’s unique cultural history and background into a standardized form required by the census. These negotiations were further complicated by a power imbalance and racial divide as the vast majority of enumerators in many states were white. For the 1940 census, and with any other datasets, Bouk reminds us that the process of data collection is far from an impartial transfer of information, but, in fact, represents a complex negotiation that requires close attention if we are to fully understand the scope and quality of the data we are analyzing.

The final stage in the process that the book covers is how the data was used by various entities after it had been cleaned, categorized, and published. The aggregated population numbers were publicized but the central tenant of the census was individual privacy as information was not going to be shared with other government departments. However, shortly after the 1940 census was completed, the US formally joined World War II. One of the dark sides of the Census’ celebrated history is how they partnered with the military to share information that led to thousands of innocent people of Japanese ancestry, including many lawful US citizens, being illegally detained in internment camps. As there are frequent conversations today about the role of privacy and data, Bouk provides us with a historical reminder that these discussions are not abstract ethical conversations, but have powerful human implications.

When we visualize various types of data and use those visualizations to tell stories, we should take a minute to consider the story of how that data came to be in the first place. Rather than uncritically assuming the objectivity of data we work with, this book calls us to strategically assess the frame of the dataset, the way in which the data was gathered, and how we are using it. This book is a crucial read for anyone within the data visualization community who wants to learn how to read the stories behind the data.

Dan’s book is available now. Find it at several online outlets, including Macmillian’s site and Amazon!

Disclaimer: Some of the links in this post are Amazon Affiliate links. This means that if you click on the link and make a purchase, we may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Joshua works on the Urban Innovation team at the National League of Cities (NLC) where he leads the organization’s data visualization portfolio. He specializes in leveraging data to inform local policymaking and in amplifying best practices through data storytelling. Based in Cincinnati OH, he is an electric bike enthusiast and passionate advocate for active transportation.