When presale tickets for Taylor Swift’s Eras tour were released in November 2022, Ticketmaster’s website was woefully overwhelmed. The site crashed, bots snatched up tickets, and millions of Taylor Swift fans, after waiting hours in a queue, were left empty handed. As the digital dust settled, the bad news only continued. Not only did Ticketmaster cancel their general sale (due to dwindled ticket inventory), but the only available tickets were listed for up to 20 times their original price on resale markets.

For context, I have been listening to Taylor Swift since I was 12. Over the years, her music has been the soundtrack to my heartbreak, my happiness, and my growth into womanhood. I have cried, laughed, and belted out to all her songs. And if I don’t sound like a truly mad Swiftie by now, I can say with confidence that seeing her Reputation tour alongside two of my best friends was the best night of my life.

Suffice to say, I could not fathom not seeing her Eras tour.

Looking back on it now, I realize (as ridiculous as it sounds) that I passed through something like the five phases of grief in my search for Taylor Swift tickets. Denial and anger after the initial Ticketmaster fiasco; bargaining as I scoured Facebook and Twitter for resale tickets; depression when I realized there were millions of people just like me, many of whom were being scammed; and, finally, acceptance when I resigned myself to buying marked-up tickets on a reputable site like SeatGeek or StubHub.

At this point it was March, and I was looking to buy tickets for the show nearest to me (MetLife stadium in late May). My only remaining question: was there an optimal time to buy tickets? Was it now? Would tickets only become more expensive? Or was there an intelligible pattern to decode? A reasonable way to buy unreasonably priced tickets?

Ticketmaster, Look what you made me do

To answer these questions, I consulted my inner dataviz engineer. After realizing that manually checking prices on StubHub and SeatGeek was unsustainable, I began doing research on their APIs. SeatGeek, compared to StubHub, had more documentation and sample code available online to access their API, which provided aggregated pricing metrics for each show.

So for example, on March 22nd, I started pulling the average, median and lowest prices of all SeatGeek listings for the April 13th show in Tampa. Repeating this until the day of the concert, I would be able to see trends in day-to-day ticket pricing, and not only for Tampa, but for every city and every date on the Eras tour. Initially, I manually added each day’s data to this ongoing dataset, but, for obvious reasons, then wrote Python code that grabbed the day’s data from SeatGeek and wrote it to a Github repository (thanks ChatGPT!).

Now here it was: the moment when I’d truly use my dataviz skills for a noble cause. I would visualize this data to see, at a moment’s glance, trends in pricing, and to determine the exact moment when I should buy my tickets.

What happened next is what I would consider a developer’s dream–the first version of the viz became (more or less) the final version. Creating a data visualization typically involves multiple cycles of design and development, spurred by user testing, to ensure that the final product meets the audience’s needs. Throughout a project I usually have a running list of to-do’s and bug fixes. And this, of course, is as it should be.

But this pet project, arguably the least intuitive and worst visualization I’ve made so far, had a very particular audience with very particular needs (It’s me, hi, I’m the user it’s me!). With limited time, I did not fuss over clear axes or helpful explanations. I did not fret over the ugly UI, lack of a mobile-friendly design or (relatively) non-breaking bugs. All the extra care I’d usually apply to making my viz universal (no doubt the crux of our profession), was put into servicing its basic functionality. This was the first time I’d created such a simple and intimate project, and with that came a liberating joy.

The result … Ready for it?

So how did I use this viz? Now that I’m writing for a larger audience, a longer explanation seems due.

In the image above, each set of positive and negative bars represents a show on a particular date. The horizontal axis represents time, the positive vertical axis represents the selected ticket pricing metric (average, median, lowest, etc.), and the negative vertical axis represents the number of SeatGeek listings for that show’s date. Shows typically take place Friday to Sunday. Each bar’s height represents the pricing metric (for positive bars) or number of listings (negative bars) as of the date represented by the red line. This date can be adjusted using the range slider to see the general pricing trend of all shows over time. Hovering on a bar shows the historic pricing for that specific show.

Play with the live viz here.

So what did I divine from all this work? Generally, I noticed that prices increased in the weeks before a show, with a spike occurring in the middle of the week leading up to the show. Then, however, something interesting happened: On the Friday before a show, prices tended to drop dramatically. Culling through Swiftie Facebook groups and Twitter accounts, I realized that this was caused by tickets that Ticketmaster was releasing the very weekend of the concerts. Unsurprisingly, many of these tickets were then immediately posted for resale on SeatGeek, thus increasing supply and decreasing the price of tickets. Since buying the face value tickets released from Ticketmaster would be near impossible (though of course I’d try), this would have to be my repurchase window–at the eleventh hour, the very weekend of the shows. Though waiting till the last minute seemed risky (and oh, how that wait gave me a few extra grays), I decided to trust my visualization.

When Ticketmaster released additional tickets two days before the concert, I bought a resale ticket on SeatGeek for the May 28th MetLife show. The ticket—eye-watering transaction fee included—was not cheap. And by ‘not cheap,’ I mean it was expensive—as in, ‘a month’s rent in New York’ expensive, or, for the more mathematically inclined, ‘add an extra zero to the original price’ expensive. As my adrenaline waned, a sobering reality set in. What had I just done? Had I really spent all that money in one fell swoop? And what if the concert turned out to be just like any other? What if it failed to meet my impossible expectations?

All weekend long, I questioned my decision, sick with both buyer’s remorse and that hopeful malady known as excitement.

Buyer’s remorse? Shake it off

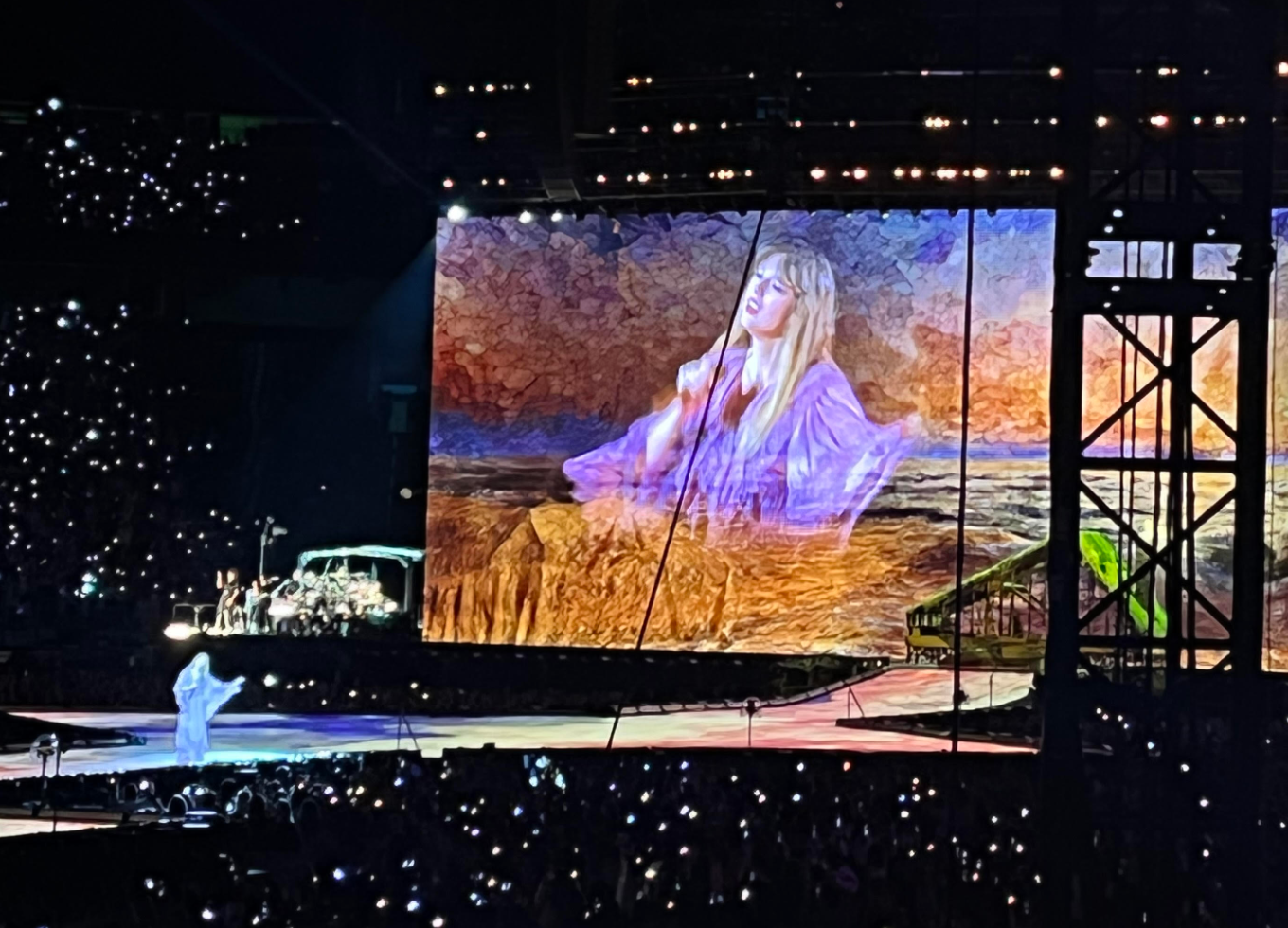

But to say that the show didn’t disappoint is a vast understatement. It was the best night of my life (yes, humbly dethroning my previous best night, at her Reputation concert). Her singing was flawless, her performance intimate. The stage sets were immersive and grand, the lighting mesmerizing and psychedelic. From nosebleed seats, a normally disappointing bird’s eye view was transformed into a unique perspective of coordinated visual effects. In ‘Mastermind,’ she sings, ‘Checkmate, I couldn’t lose,’ and at one point a shifting chessboard was projected onto the stage floor, with dancers standing in for chess pieces—a sight unavailable to the fortunate few with floor seats. Everything—the lights, dancers, and sets—was coordinated in a manner that transcended a normal concert and approached something closer to a Broadway show or, as a devout Swiftie might say, a religious experience.

As she traversed the eras of her career, so I traversed the eras of my life. When she sang about losing her grandmother in ‘marjorie,’ I looked up at the sky and fought back tears thinking of my Grandpa. When she sang ‘Shake It Off,’ I recalled belting out the very same lyrics with my college roommate as we commiserated over stupid boys. When she crooned about the first fall of snow in ‘All Too Well,’ I suddenly remembered leaving a college party late one night and being struck by the sight of snow falling fresh in New York City. I remembered how the streetlights had glowed with an aura of snowflakes; how I had listened with uncanny amazement to the unusual silence; and how, upon seeing the magical sight, I shared a moment of truce with a guy I was on the rocks with.

And here’s the thing: I wasn’t the only one having this experience. It was as if she touched every person in that stadium of 80,000. When she sang ‘betty,’ a recent song from folklore, I was shocked by the teenage girls around me who shouted along. The song, about a high school love triangle, was one where, despite loving the music, I’d found the lyrics a bit immature. But now I realized that Taylor, while maturing in her musical themes, still made an effort to connect with a younger audience, much in the same way that ‘The Story of Us’ had connected with me a decade earlier. And hearing it again, ‘betty’ became clever in a way that her earlier songs weren’t, incorporating intentional storytelling that deviates from her usual autobiographical style. (My turn to scream came a bit later, during the most recent era of her life, when the lyrical themes shifted from young love and heartbreak to the competing obligations of a career, relationships, and societal expectations.)

But the most touching moment of the concert occurred when, in the surprise acoustic section, Taylor sang ‘Welcome to New York,’ a synth-pop anthem from her 1989 album. At home, I’d normally skip this song, finding its beat a little too relentless. But hearing it intimately stripped down to her voice and her strummed guitar chords, I realized that my journey to standing in that stadium began much more than a few months ago.

I moved, not just to New York City, but to America 10 years ago. It was as far removed from a small Caribbean island as it was possible to be, and I distinctly remember the initial feeling of panic. Through the ups and downs, I made this my second home. And those ups and downs proudly mark the NYC era of my life. I made best friends and met the love of my life while surviving the stress of my undergraduate engineering degree. I struggled through multiple job hunts and a career pivot, but now get to do what I love every day (moving through appropriate design-development iterations of course!). It was a new soundtrack and I did dance to this beat – still do.

So after this experience, I can see why Eras tour prices have only kept increasing over time… I may or may not be updating my visualization to keep an eye on future ticket prices…

Editing support: Rob Aldana

Kelsey Nanan

Kelsey Nananis a data visualization developer from Trinidad and Tobago. She is currently freelancing and was previously part of McKinsey and Company’s Data Visualization Lab. She became passionate about data viz and open data while receiving her M.S. in Urban Science at New York University. In addition to listening to Taylor Swift and creating interfaces that are fun and intuitive to explore, Kelsey loves yoga, baking and Shaking It Off.