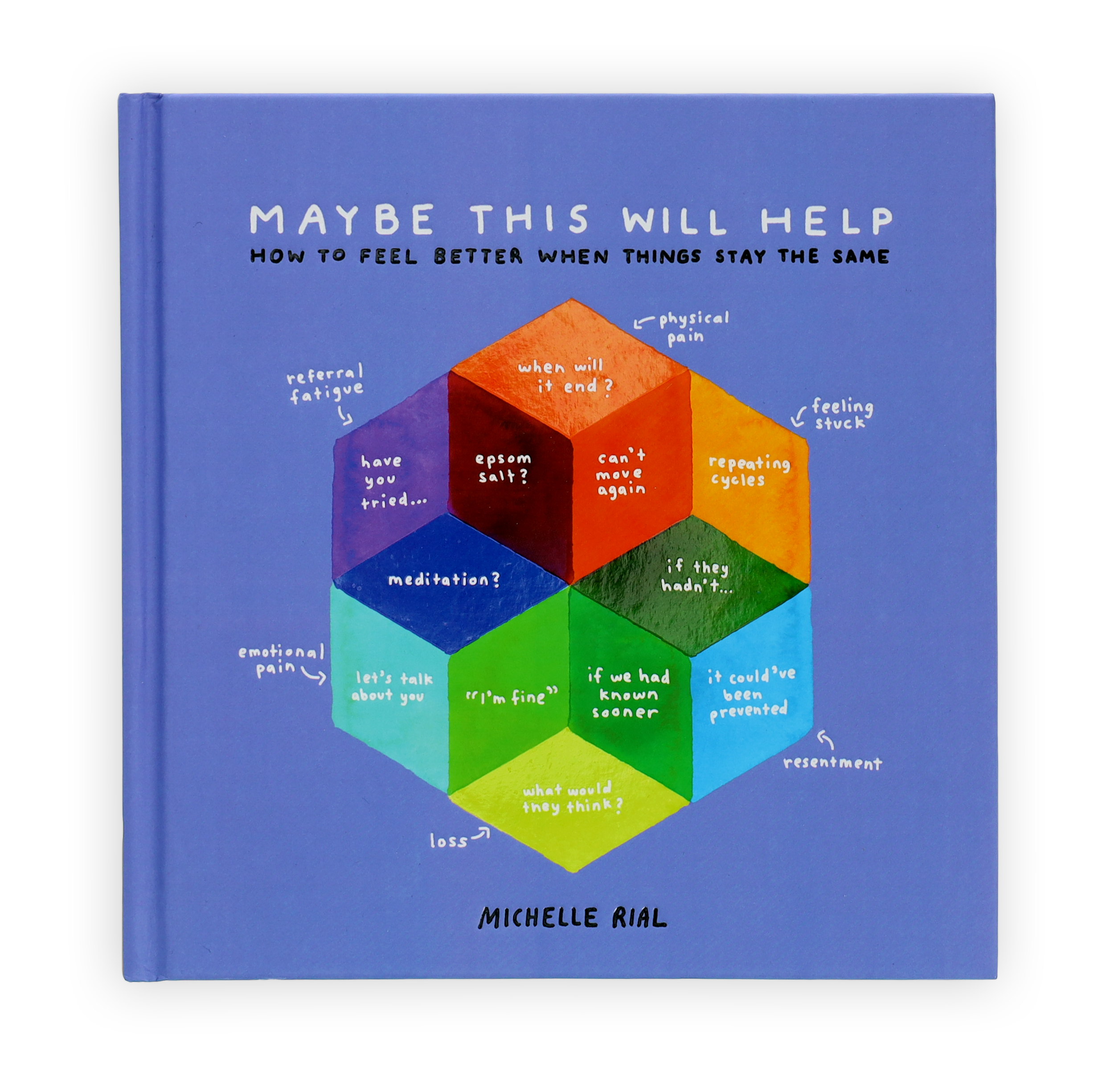

If there’s one thing that the last 18 months have shown us, it’s that we are all Going Through Some Stuff. Maybe that’s dealing with illness (your own or that of loved ones), frustrations of working from home, frustrations of not being able to work from home, burnout from trying to parent while working, or just exhaustion from 18 months of stress and disruption. So while illustrator and information designer Michelle Rial’s new book Maybe This Will Help is not about the pandemic – it’s about her own struggles with chronic pain and grief – it feels like it’s arrived at exactly the right moment.

We could all probably use a little help. Michelle’s book offers that by being simultaneously lighthearted – even joyful and funny! – and contemplative. It’s a book that feels like a hug from a friend: understanding and encouraging, but not self-serious.

Plus—it’s full of charts!!

Based on Michelle’s first book of charts, Am I Overthinking This?, and the teaser images I had seen on social media, I expected Maybe This Will Help to be another wryly funny book of cleverly-designed graphics. And it is—but what I was not expecting were the deeply personal essays that elevate it from a clever coffee table book to something more thought-provoking and more, well, helpful. If you are a person who (1) loves charts, (2) particularly loves funny charts, and (3) can relate to Going Through Some Stuff, then this book probably needs to be on your reading list.

For more on the behind-the-scenes process, I reached out to Michelle; her responses to my questions are below. (You can read Nightingale’s Q&A with Michelle about her first book here.)

Maybe This Will Help is available for pre-order now, with an expected release date in mid-October.

Claire Santoro: Both your books are full of charts—do you think of yourself as a data person? What draws you to charts?

Michelle Rial: I wanted to be a data person for a really long time, and in the past I gravitated toward those huge “by the numbers” infographics and gradually moved toward using data components to tell a tiny story. I feel a little bit like a data impostor, because when I look at large sets of data it’s overwhelming so I’m impressed with real data people.

I have always loved math and conceptual art, and my dad was a physicist so anytime I’d walk into his office he’d be running Mathematica with some type of mathematical model on the screen or have charts scribbled in his notebooks, so it feels like a language I grew up with. I consider myself a poor verbal communicator—it takes me a lot of effort to communicate something in a way that makes sense to other people, and it comes much more naturally and clearly to communicate visually. With a simple chart, it can sometimes take as few as three lines to communicate an idea.

CS: What do you think draws readers to charts? (Here at the Data Visualization Society, we all obviously love charts, but we recognize that we are not The General Public.)

MR: They can be quickly and easily absorbed, depending on the chart.

CS: Where do you get your ideas for the charts in your books? I’m picturing your workspace as a hodgepodge of watercolors, bouncy balls, hardware, and other random trinkets.

MR: That’s exactly right! I have tote bags full of trash, basically. I collect random objects that might be useful for future charts, but many of them that haven’t sparked any ideas (yet) make me feel a bit hoarder-y. I’ve been looking for my tweezers for about two months, and you actually just reminded me that they’re probably in one of those bags.

CS: How did you actually make the charts in the book? How much is done by hand versus digitally?

MR: For the first book, almost everything started off by hand, because I was trying to use the computer as little as possible in order to not agitate chronic pain issues related to computer use. I would write around an object and photograph it, whereas in the past I may have designed it digitally. In the end, the object + text method backfired a bit because I needed to separate the image and text layers in Photoshop for potential translations which ended up being a lot of computer work.

For the second book I took photos of objects, then drew around them on an iPad. It doesn’t feel as interesting or artistic as a process, but it removes the heavy post-production step and the whole point of the style is minimal mouse/computer work, which is what causes me the most pain.

CS: Unlike Am I Overthinking This?, which was more lighthearted, your new book takes a more serious, personal look at life, chronic pain, and grief. Did that make this book easier or harder to write?

MR: It was so hard to write, but at the same time, everything rushed out of me in long spurts. I guess I could say it was cathartic to write, but wondering what people will think about it is harder. The other book feels more universal, and this one is deeply personal (which I’m told is universal). With some of the things I write about I worry that I’m not portraying it “correctly,” like someone can say “hey, that’s not what my chronic pain is like,” which is why I chose to add essays to this book to make it clear that I’m not trying to do that. It’s my story and if you relate to it and if it helps you without trying to tell your story for you, well, that’s great.

My hope is that, because these people are so often spending money on cures and things, someone will gift them this book (in that sense, I’m glad it’s a “gift book”) so they don’t have to buy it themselves. The intro of the book is titled “I hope this is not a scam” because people trying to heal are always spending all their money, and I feel guilty asking them to buy yet another thing that might not actually help (though I hope it does, in whatever way it can).

I had been wanting to make something related to chronic pain, but as I was writing it, the grief I was experiencing was very fresh and kept rising to the top, and sort of weaved itself in as part of a larger story.

CS: The book is titled Maybe This Will Help, and indeed, although the specific issues you write about are yours alone, the charts and commentary feel as if they could apply to almost anyone. Did making the book help you? That is to say, is there hope for the rest of us?

MR: I got some reviews of my first book that were like “Didn’t help me with my overthinking AT ALL, just a bunch of pictures,” and there were kind and encouraging reviews that I obviously ignored in favor of the negative ones, which I will let haunt me in perpetuity. There are many reasons I haven’t promoted this book as fiercely as I did the first one, and one of the reasons is … what if it DOESN’T help? I guess it’s sort of the point of the book itself that that one magical thing just isn’t going to be the cure-all. I also hope it serves as some form of permission to try to find a way to stop doing that one thing that’s making everything worse, if at all possible.

The act of making the book helped me emotionally, but anything where I’m trying to meet a deadline (even if I’m sort of “optimizing” my style for the least amount of pain) is going to cause flare-ups and further strain on my neck and arms and hands, etc.

As for “Is there hope for the rest of us” — I hope so. I don’t really know how to answer that! Hope gives us the energy for change and action and forward movement, so it’s important to hold on to it. There is so much hopelessness and despair in rock bottom, but generally if you’re at the bottom you can only go up from there, so it’s important to try to remember that. I hope that’s not too platitude-y.

For even more on the behind-the-scenes process of publishing a book, told in a series of 10 pie charts, check out Michelle’s 2019 illustrated column in the New Yorker.

And remember that Maybe This Will Help is available for pre-order now, with an expected release date in mid-October.

Claire Santoro is an information designer with a passion for energy and sustainability. For 10 years, Claire has worked with governmental agencies, non-profit organizations, and higher education to accelerate climate action by communicating complex information in an engaging, approachable way. Claire holds an M.S. in environmental science from the University of Michigan.