An all-black team led by W.E.B. Du Bois made one of the most powerful examples of data visualization 118 years ago, only 37 years after the end of slavery in the United States.

Activist and sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois created “The Exhibit of American Negroes” at the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris in collaboration with Booker T. Washington, prominent black lawyer Thomas J. Calloway, the assistant librarian at the Library of Congress Daniel Murray, and students from historically black college Atlanta University.

While Du Bois’s legacy is cemented in American history, his data visualizations remain relatively unknown. I’m passionate about Du Bois’s story and have been discussing it via a series of articles through the lens of a UX Designer working in data visualization. My hope is that these posts inspire more academics, designers, and data visualization specialists to explore this work further in order to place the work into the proper historical significance it deserves.

The word “Negro” will appear frequently in this series. It’s not a word I take lightly. It is the term Du Bois references throughout this phase of his career and I think it’s best to honor and contextualize his use of language for this article.

The Story of “The Exhibit of American Negroes”

When I began this series it was spring, and now as I finish it, the shadows grow longer and autumn is slipping into winter. So too is the story-arch of “The Exhibit of American Negroes.” It is a story rich in promise with significant accomplishments, but ultimately, slips into darkness. It’s an amazing story.

It’s 1899 and a century of unprecedented change is coming to an end. The very term ‘science’ was invented in 1833 and the impact of scientific invention was omnipresent across cultures. Profound social change was underway and slavery was greatly reduced on a global scale. The painful mid-century Civil War in the United States reshaped the young country and brought about the 13th Amendment which abolished slavery in 1865.

As a result of Reconstruction, many former slaves were now granted unprecedented rights under the 14th Amendment. At the same time, many racist lawmakers gained power across the southern states and Jim Crow laws began to radically roll back these rights under the guise of “separate but equal” segregation.

Outraged at the racist displays found in the 1893 Chicago and 1895 Atlanta Expositions, lawyer Thomas Calloway sends a letter to hundreds of African-American leaders across the country:

“To the Paris Exposition… thousands upon thousands will go… a well selected and prepared exhibit, representing the Negro’s development… will attract attention… and do a great and lasting good in convincing thinking people of the possibilities of the Negro.”

The leaders rally to his call and decide that an exhibit will be created under the direction of the brilliant young sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois and will present the very best of African-American life and culture. $15,000 in funding is unanimously passed by Congress and signed by President Mckinley.

What follows is a frenzy of activity.

In just 4 months, prominent citizens, educators, and students across the country begin to assemble the materials. “The five great negro schools”: Atlanta, Fisk, Howard, Hampton and Tuskegee Universities prepare exhibits. The assistant librarian of Congress, Daniel Murray, collects more than a thousand books and pamphlets by Negro authors while Du Bois and his students conduct a sociological study in Georgia and draft the 60+ charts. War heroes are documented. Businesses, churches and black newspapers from across the country send in photographs of their finest and best. 400 patents are collected. As a subtle nod to systematic prejudice, Du Bois hand-writes over 400 pages documenting the Black Codes. As a final touch, a bronze sculpture of Frederick Douglass is included.

Pulitzer prize-winning scholar David Levering Lewis in the book A Small Nation of People writes about the effort: “The Negro exhibit at Paris was a racial imperative, a momentous opportunity and obligation to set the great white world straight about black people.”

The resulting exhibition was a targeted attempt to sway the world’s elite to acknowledge the American Negro in an effort to influence cultural change in the USA from abroad. David Levering Lewis continues “In many ways, The Negro Exhibit… represented the last hurrah of men and women of culture and accomplishment who still aspired to full citizenship rights regardless of color.”

After working tirelessly on the exhibit for months, Du Bois was “threatened with nervous prostration… and had little money left to buy passage to Paris” — but arrived just in time. He quickly sets up the exhibit in time for the judging, despite missing some of the materials from the Universities, but the judges still recognize the Exhibit by awarding it several prizes including an overall Grand Prix and Du Bois a special Gold medal.

While the exhibit was praised by officials and the Paris Exposition as a whole broke attendance records, the direct impact of “The Exhibit of American Negroes” is hard to measure.

While the African-American press reported on the exhibit with gleeful excitement and enthusiasm, the European media only moderately mentioned the effort — and only then as a small element of the massive Exposition. The white American press, however, completely ignored the exhibit and the American public at large remained unaware of the “The Exhibit of American Negroes”.

David Levering Lewis writes about the poignant aftermath of the exhibit: “What Du Bois and Calloway had wanted to demonstrate to the world about the progress and promise of people of color in America had become almost an epistemic impossibility for the majority of their white countrywomen and -men by the dawn of the twentieth century. For, just as a significant percentage of Du Bois small nation of people stood ready to walk onto the world stage as aspiring, able, even assimilated, participants in the social contract, a peculiarly American version of white supremacy twinned with [master race] democracy, consigned all black people to the shadowy margins of the national life where their invisibility would long remain indispensable to the identity of white people.”

Despite the work by Du Bois, Calloway, and the extended community to show off the best of what African-Americans had to offer, the exhibit was met with indifference as the exhibition had failed to bring about social change.

This brings me to the biggest question that I’ve been considering since I began this project:

Why don’t more people know about Du Bois’s data visualizations?

The story of “The Exhibit of American Negroes” is both inspiring in its brilliance and originality, and tragic in its overlooked state — barely even a footnote in history. While writing and thinking about this work, I have developed a few thoughts as to why this work is just not better known.

1. The Exhibit did not bring about social change.

As discussed at the close of my last article, Du Bois chanced upon the actual remains of Sam Hose who was lynched by a crowd of hundreds, his body was ripped apart and distributed around the state. It shook Du Bois to the core. In the face of such violent hatred, Du Bois realized science just wasn’t enough:

“Two considerations thereafter broke in upon my work and eventually disrupted it: first, one could not be a calm, cool, and detached scientist while Negroes were lynched, murdered, and starved; and secondly, there was no such definite demand for scientific work of the sort I was doing…”

Had the exhibit caught the attention of the European press, maybe Du Bois would have made a name for himself as a sociologist instead of a social activist, and the “Du Bois Spiral” would be considered equivalent to Florence Nightingale’s “coxcomb” in historic significance.

2. Prejudice in the Sociological community obscured Du Bois’s importance

After his return from Paris, Du Bois became increasingly disenchanted with social science — especially in the face of violence and racism. Toward the end of his life he reflects on his change of heart, writing: “So far as the American world of science and letters was concerned, we never ‘belonged’; we remained unrecognized in learned societies and academic groups. We rated merely as Negroes studying Negroes, and after all, what had Negroes to do with America or science?”

Recognized social theorist Patricia Hill Collins argues that “different versions of a logic of segregation shaped all aspects of American society, including American sociology”. While Gurminder Bhambra, in his article outlines the stark reality: “the lack of attention given to alternative traditions of thought within the metropole has tended to elide the colonial past and drown out other voices…”

In studying the Negro, Du Bois simply explored a subject that White America just didn’t care about — especially at the dawn of the twentieth century. Despite his academic pedigree and exhaustive rigor, Du Bois’s work was largely ignored by white academia which left his work underexposed. Certainly calls for re-exploring Du Bois’s sociological importance have been regularly called for over the years, but only in the past decade can his impact be felt more clearly.

Just last month Harvard University hosted a symposium to discuss Du Bois’s impact on sociology. The lectures and panels retraced his rise to prominence, discussed his methodical practices, and Du Bois’s importance in the world today. Indeed, as you can see to the left, the ‘Du Bois spiral’ is the leitmotif of the conference — an icon of hand-made progress and precision.

3. As racism became more vicious, Du Bois became more outspoken

Looking back at his time in Paris and as a social scientist, Du Bois recalls the very real needs of those trying to break through to a larger audience:

“Where had I failed? There were many answers, but one was typically American, as the event proved; I did the deed but I did not advertise it… in the long run Advertising without the Deed was the only lasting value. Perhaps Americans do not realize how completely they have adopted this philosophy. But Madison Avenue does.”

Three years later Du Bois published The Souls of Black Folk. It was a different kind of book than what Du Bois had previously published, one that married Negro culture to current events and history but with a palpable anger that demanded attention. Du Bois struck a deliberately non-scientific tone in the book, using fragments of Negro spirituals to illustrate his point rather than data visualizations. His change of approach worked and the book’s emotional appeal and intellectual brilliance was able to connect with a global audience bringing Du Bois the attention he sought and deserved.

4. A small chapter in a massive career

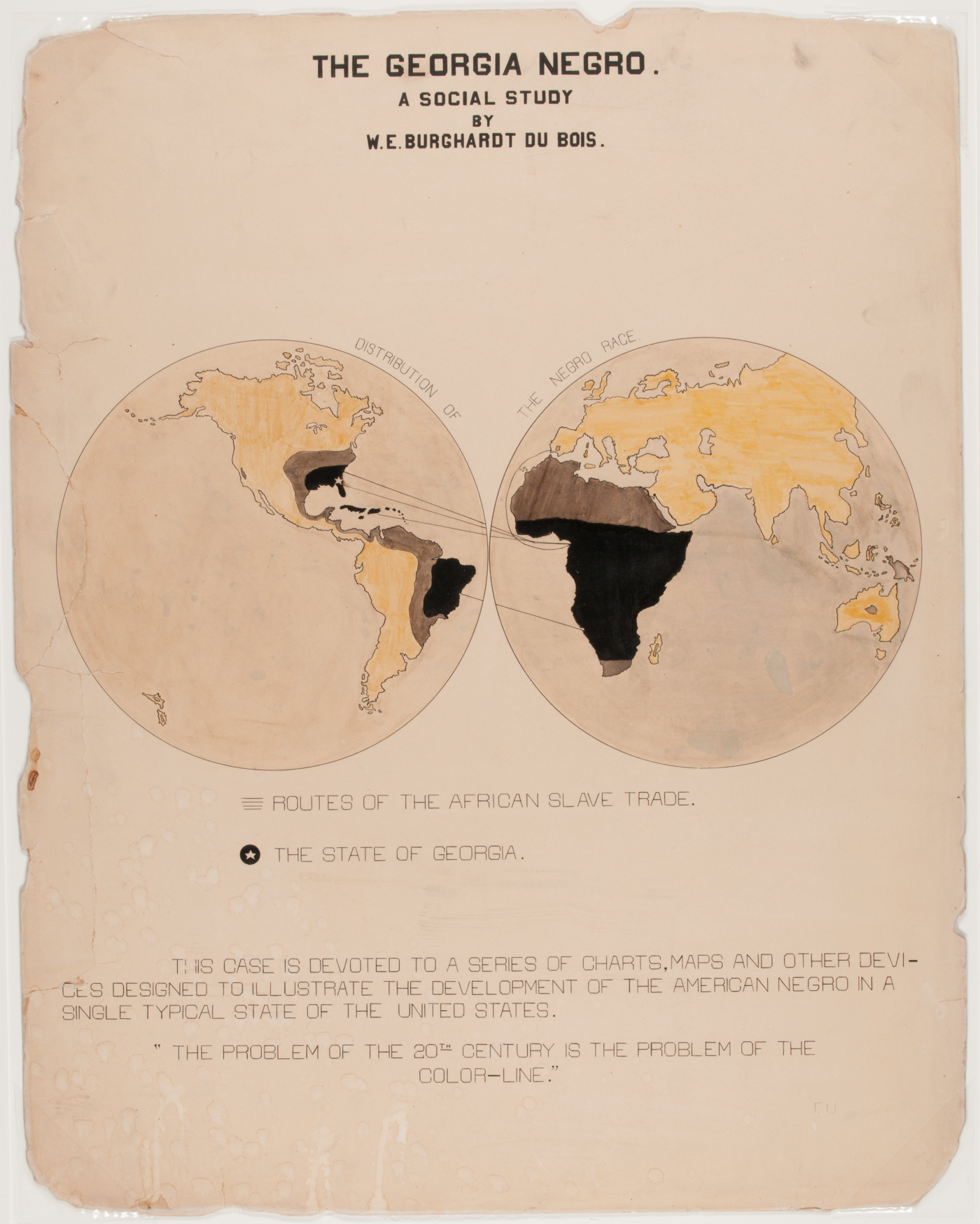

Du Bois begins the first series of charts with the now famous phrase: “The problem of the 20th-Century is the problem of the color line.” It is a statement he used in his speech at the First Pan-African Conference in London that same year, and it is also included in the introduction of The Souls of Black Folk.

In crafting an exhibit exploring the excellence of the 19th-century Negro, Du Bois assembled the most definitive counter-argument to Booker T. Washington’s Atlanta Compromise of 1895. His passionate refutation of Washington in The Souls of Black Folk set Du Bois on a path that eventually establishes him as the leader of the Niagara Movement, and co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

His tireless activism, lectures, and books saw him to be a central figure in global politics. A renowned figure hosted by world leaders, perpetually independent (and controversial), Du Bois was a socialist, then a communist, and eventually expatriated to Africa.

He died on August 27, 1963 — the day before the famous civil rights March on Washington. Roy Wilkins, a civil-rights leader who had worked with Du Bois at the NAACP, announced Du Bois’s death at the march and asked for a moment of silence:

“Regardless of the fact that in his later years Dr. Du Bois chose another path, it is incontrovertible that at the dawn of the twentieth century his was the voice that was calling you to gather here today in this cause. If you want to read something that applies to 1963 go back and get a volume of The Souls of Black Folk by Du Bois, published in 1903.”

The Civil Rights Act, was enacted the year after Du Bois’s death. It outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin and prohibits unequal application of voter registration, racial segregation in schools, employment, and public accommodations. The rights that Du Bois had fought his entire life for were finally a reality.

Acknowledging the legacy of W.E.B. Du Bois

As history is being rewritten to be more inclusive, Du Bois’s innovations in statistical chart-making deserve an equal place in the history of data visualization as well. As his influence triggers new research efforts, so should his work inspire new methods for visual communication.

A major advancement in the cause of exposing Du Bois’s work to a wider audience can be seen in the new book “W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America.” Co-edited by Britt Rusert and Whitney Battle-Baptiste with essays by Aldon Morris, Mabel O. Wilson, and Silas Munro, the book discusses Du Bois’s work predominantly from an African-American studies perspective and includes annotated prints of all the charts in the collection of the Library of Congress.

With every new article, the story of “The Exhibit of American Negroes” continues to spread Du Bois’s daring, brilliance and vision. Hopefully his work will inspire historians, data journalists and designers to continue to challenge the conventions of the world around them by telling stories with data in new and innovative ways.

I’ll end with a quote from Du Bois’s Autobiography.

“On mountain and valley, in home and school, I met men and women as I had never met them before. Slowly they became, not white folks, but folks. The unity beneath all life clutched me. I was not less fanatically a Negro, but “Negro” meant a greater, broader sense of humanity and world fellowship. I felt myself standing, not against the world, but simply against American narrowness and color prejudice, with the greater, finer world at my back.”

This is almost the end of the series, and as I have written before, it’s been a surprising journey. In the final article in this series I’ll discuss an extremely exciting discovery that I’ve made and in addition, I’ll list all the charts in sequence and even supply links to the majority of my research materials.

The six-part series:

W. E. B. Du Bois’ staggering Data Visualizations are as powerful today as they were in 1900

An introduction to the 1900 Paris Exposition, and context for a few charts on history and population growth.

II. Data Journalism and the Scientific Study of “The Negro Problem”

Places this body of work within Du Bois’ larger sociological focus and continues the exploration of many of the charts from the exposition with a focus on education, literacy, and occupation.

III. Exploring the Craft and Design of W.E.B. Du Bois’ Data Visualizations

A detailed examination of how Du Bois drafted his charts, a consideration of this work as a precursor to modernism, and a discussion of his more artistic charts on land ownership and value.

IV. Style and Rich Detail: On Viewing an Original Du Bois Chart

Discoveries on viewing an original chart and further exploration of Du Bois’ more innovative designs dealing with occupation, business, and mortality.

V. Du Bois as Social Scientist and the Legacy of “The Exhibit of American Negroes”

Discusses Du Bois’s body of work and his frustrations with social science despite widespread attention.

VI. The Exhibition as a Whole: an Exciting Discovery

To close out the series I present a previously unknown chart from the series, and discuss the importance of understanding the sequence of the works.

This article originally appeared in Medium but in moving to NightingaleDVS.com, I edited the original text mostly to update some grammar and language substitutions, January 2023.

Jason Forrest is a data visualization designer and writer living in New York City. He is the director of the Data Visualization Lab for McKinsey and Company. In addition to being on the board of directors of the Data Visualization Society, he is also the editor-in-chief of Nightingale: The Journal of the Data Visualization Society. He writes about the intersection of culture and information design and is currently working on a book about pictorial statistics.